Our world is inherently precarious, confusing and often overwhelming. So we develop belief systems and ‘truths’ as individuals and societies that allow us to navigate and survive it.

These basic yet crucial constructs help turn a frightening place into a manageable one. I’m not talking about religious beliefs – though for so many these are obviously of fundamental importance too – no, what I’m referring to is something more basic than that. It’s the belief that good will triumph over evil. The belief that those who work hard will be rewarded. The belief that following the rules benefits all. The belief that laws are just. That the guilty will go to jail and the innocent will walk free. The belief that if I keep my children safe, they will survive to adulthood. The belief that if I instil the concept of Stranger Danger into them enough, they will not get into an abductor’s car. The belief that they will keep breathing. The belief that if you close your eyes you will sleep at night.

When these truths are tested, when they are found wanting, one’s whole belief system can come tumbling down and the psychological fallout that ensues can be terrible. Think of the righteous indignation you feel when someone merely queue jumps and gets away with it. When someone blatantly lies and goes unpunished. You want a divine force, an all-seeing policeman to intervene and dispense justice, preferably of the lightning bolt variety. And when they don’t, you feel like a fool for following the rules in the first place.

The first erosion of my belief system came when I was twenty and following a barrister for work experience. I was studying Law at Oxford University and deciding whether to go down the solicitor or barrister route. The barrister was defending a client accused of rape, it was a summer’s day, and the court room was hot and stuffy. I had such an idealistic view of the law from studying it in the abstract. My degree was all about ideas and debate. We read articles on the extent to which the law should be able to infringe on individual liberty. We read Sir William Blackstone’s assertion that it is better than ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer. This court room, this case, was my first experience of law outside the library or a fire-warmed tutor’s study. And it shocked me. And it wasn’t even the nature of the case or the evidence given. It was the fact that half the jury members didn’t seem to be listening. They were bored. They didn’t want to be there. And I could feel my own prejudices come into play. The defendant wore blue-tinted glasses. Which to my mind made him dodgy. But I shouldn’t have been paying attention to the lens colour. I should have just been listening to the facts. Being there, that day, threw my confidence in the infallibility of our justice system.

The second erosion came when my baby stopped breathing.

When my eldest daughter was just nine months old, she suffered from a febrile convulsion. My husband and I had never heard of this particular form of torture, so we were completely unprepared. She stopped breathing, her skin turned blue, and her eyes rolled back in her head so that only the whites were visible. I thought she’d died. For two whole minutes I thought my baby was dead. Luckily, she started breathing again of her own accord and the ambulance crew arrived a matter of minutes later and were incredible.

Still, those two minutes were all it took to damage a large part of my belief system. I forced myself to stay awake, twenty-four hours a day, for a whole week. I lay next to her at night, eyes wide open, watching her sleep. Just to make sure she kept breathing. Just to make sure she survived till the next morning. And in that week, I destroyed my own sleep cycle and have suffered from recurrent insomnia ever since. I no longer believe that if I lay my head on a pillow and close my eyes that sleep will necessarily come.

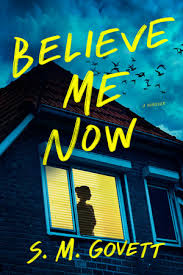

When I decided to write my debut thriller, I wanted to create a situation that threw my protagonist – Natalie – ’s belief system into similar disarray. I wanted her to be a solicitor, as I ended up being, who loses faith in the law when her attacker is found not guilty. But then I wanted to twist the knife deeper.

So I thought: What else do I believe in? Who do I trust the most? And the answer was my husband. So then I thought: how would I feel if everything I thought to be true about my marriage started to unravel? Would I believe him, no matter what, or is there something that could make me hesitate? What if he were accused of the same crime that happened to me? How could I believe him if no one had believed me? Wouldn’t it make me re-evaluate everything?

My favourite sort of books and TV shows are the ones that force me to ask myself the question: what would I do in that situation? What would I think? My husband and I will often pause the TV and begin animated discussions that last longer than the actual episode does.

What I really hope is that readers will engage with this story in the same way. I want people to put themselves in Natalie’s shoes and imagine how they would react if everything they held true started to disintegrate around them and they were left being able to trust no one, not even themselves.

Because even the word, BELIEVE, also contains the word LIE.

***