Nostalgia, in the wake of the Tate-LaBianca murders, redolent of a greener, guileless city, paled Robert Towne’s vision. Thick with memory, he discovered, in a pile of West magazines Julie had collected, “Raymond Chandler’s L.A.,” a photo essay alive with his own childhood. There, in ringing color, was the green Plymouth convertible. There was J. W. Robinson’s department store. The lazy gush of banana leaves. An imperious, piercingly white Pasadena mansion, with its porte cochere, towering over the palms like Shangri-La. Their colors threw Towne into the past. “The best time to see Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles,” he read in West, “is in the grey mists of the early morning, or better still, in the very late afternoon, when streets are in shadow broken only by golden yellow sunshine; times when your eye can be tricked into ignoring the long lines of franchise eateries and gas stations, each with its own plastic sign in one or another primary color; times when you don’t notice the cheapjack apartment buildings glittering their anodized metal geegaws at you; times when your eye can pick up the Los Angeles which existed prior to 1942.” Towne had been eight in 1942. “That is not an arbitrary choice of years,” the essay continued, “for after 1942 the swarm of defense workers, the maddened construction of factories, homes, apartments, the industrial and automotive smog, all irrevocably altered the physical face of Los Angeles.”

Change.

It was a city inclined to growth, inclined to loss. “So great is the rate of change,” wrote Richard G. Lillard in Eden in Jeopardy, “and so rapid is the increase in land values, that the life of many structures is from fifteen to thirty years, and it is a rare landmark building that can survive the crane.” “Planned or unplanned,” Lillard wrote, “the Southern California cities gave way to the motor vehicle. Men tore down buildings to make way for parking lots or service stations. Men chopped down trees lining streets, broke up curbs, scraped up lawns, and widened streets to the front steps of houses.” Elsewhere the freeways were developed to tie cities together, but in Los Angeles, freeways were developed to solve congestion inside the city itself, ironically creating more congestion: More roads led to more traffic, more traffic to more roads, “which smash,” Michael Davie wrote, “the city to pieces.”

Towne could remember another Los Angeles. He was born in San Pedro, a sandy port town twenty miles south of downtown L.A. The 1930s, the 1940s: he remembered more sky, fewer impediments to the sun. The trees were not so tall in those days, and the stucco fronts of Pedro reflected light onto the brick buildings of the waterfront. Los Angeles, in Towne’s memory, was then a haven of pastel and desert moods softly dusted in hues of Spanish rust, “a light wash of colors,” he observed, “that had the delicacy of a gouache.” Even the sunsets whispered their pinks and golds. “Only the bougainvillea blinded you,” Towne recalled. “I remember the first time I saw some—an ecstasy of San Diego reds, tumbling along and over a white wall, across a trellis, then smothering a garage with its crimson wildness.”

Towne had never read Raymond Chandler before—his old roommate, Edward Taylor, was the big mystery reader—it was the loss that got him. Chandler’s detective novels preserved prewar L.A. in a hard-boiled poetry equal parts disgusted and in love, for while Chandler detested urban corruption, the dreaming half of his heart starved for goodness. Poised midway, the city held his uncertainty; Philip Marlowe, his detective, bore its losses. “I used to like this town,” Marlowe confessed in The Little Sister in 1949. “A long time ago. There were trees along Wilshire Boulevard. Beverly Hills was a country town. Westwood was bare hill and lots offering at eleven hundred dollars and no takers. Hollywood was a bunch of frame houses on the interurban line. Los Angeles was just a big dry sunny place with ugly homes and no style, but goodhearted and peaceful. It had the climate they just yap about now. People used to sleep out on porches. Little groups who thought they were intellectual used to call it the Athens of America. It wasn’t that, but it wasn’t a neon-lighted slum either.”

“In reading these words and looking at these pictures,” Towne said, “I realized that I had in common with Chandler that I loved L.A. and missed the L.A. that I loved. It was gone, basically, but so much of it was left; the ruins of it, the residue, were left. They were so pervasive that you could still shoot them and create the L.A. that had been lost.”

A city was its crimes, Towne read in West. In New York, money was the motive. In Los Angeles, where people lived far from their neighbors and loneliness dried the landscape, criminals were sicker, their crimes more personal and perverse. “One thinks of a woman incinerating her husband so that she may live with her lover,” Towne read, “of a man gnawing at himself until he is certain that his wife must be seeing someone else, and then methodically beating her half to death; of, in general, individuals so trapped within themselves that they can only contemplate slaughtering whoever is closest to them.” Who had killed Sharon Tate?

“I want a gun,” Julie Payne declared.

“No, no,” he said. “We need a dog, a guard dog.”

They drove out to a steel factory in the valley to see a pack of Komondors, “wolf-killers,” Payne said.

“Take this one,” the breeder advised, pointing to the most ferocious-looking of the lot.

“No,” Towne said. “I want this one.”

Towne brought her home, and Payne named her Scylla, but it was soon apparent she was a lady, not a killer. On the recommendation of screenwriter Carole Eastman, Towne and Payne got a German shepherd, but she proved to be as docile as the Komondor. A breeder pointed them to Tony Silas, an undercover vice cop, owner of a new litter of Komondors. Silas, at his home in Chatsworth, offered up one of the pack. Towne fell in love with it. He named him Hira. As soon as Hira came home, he ran into Towne’s office and under his desk (“Hira was a born writer’s dog,” Payne observed), bringing Hutton Drive’s dog count up to three—too many. One went to Towne’s mother, and the count fell back down to two, but Scylla went into heat and “[neighbor] Quincy Jones’s dogs were barreling under my gate,” Payne said, “and the next thing I knew Scylla’s pregnant.” Seven puppies later, Mike Nichols called. “Puppies?” he asked. “Killer puppies? I’m coming right over.” (He picked one, named it Louis, and took it home.)

In due time, Tony Silas paid a visit to Hutton Drive and instantly understood why Payne wanted that gun. Their house, up on a hill at the

end of a curled drive ay, was like the house atop Cielo Drive, distressingly isolated. Should anything happen, there would be no escaping.

“Get her the gun,” Silas told Towne. “If anybody came up this driveway,” Silas continued, “ forget it. Women shoot to kill.”

Towne got the message. “Where do you work?” he asked the vice cop.

“Right now we’re working in Chinatown.”

“What do you do there?”

“Nothing.”

“What do you mean, nothing?”

“Well, that’s pretty much what we’re told to do in Chinatown, is nothing. Because with the different tongs, the language and everything else, we can’t tell whether we’re helping somebody commit a crime or prevent one. So, we just . . . we do nothing.”

Forget it.

Towne went down to Kerr’s Sporting Goods on Wilshire and bought Julie a .38 police special, blue steel. She kept it on a closet shelf in the bedroom.

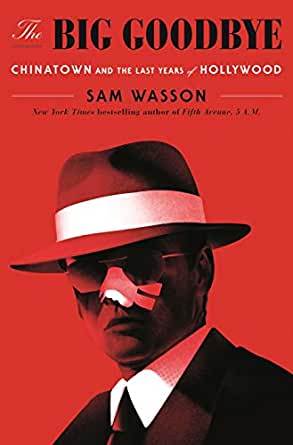

(Excerpted from THE BIG GOODBYE: CHINATOWN AND THE LAST YEARS OF HOLLYWOOD. Copyright © 2020 by Sam Wasson. Excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher.)