It is a truth, universally acknowledged, that when murder was committed in early nineteenth century England, the first men called to the scene were the famous Bow Street Runners. This intrepid squadron of proto-detectives would investigate the crime, collect evidence and uncover witnesses.

At least, that’s how I thought it worked.

When I started writing my Rosalind Thorne mysteries, I assumed that the “runners” were the foundation of what would become the Metropolitan Police force. But the more I read, the more I discovered how wrong I was.

Law enforcement in early modern and Regency England operated as a disorienting patchwork of services and jurisdictions. It was also founded on a very different set of civic ideals. Blackmail was considered private business. Forgery could be a hanging offense, even for the aristocracy. When it came to theft, the goal of the investigation—if there even was one—was to find the property. If a person wanted help recovering their property, they had to pay for it. Even the Bow Street police office operated on a fee-for-service basis. As David Cox quotes in A Certain Share of Low Cunning, his excellent book on Bow Street, “If the gentleman writes, the gentleman pays.”

But what about murder?

Murder was by definition, a breach of the “King’s Peace.” The King’s Peace was the understanding that it was the king’s responsibility to maintain public order. That meant any violent death became a matter for the Crown, and the person responsible for the investigation was an officer of the crown; specifically, the Coroner.

So, who was the Regency Coroner? What did they do and how did they do it? After some frantic searching through the digital catalogue of my local university, I found my answers in a book written by John Impey of the Inner Temple: Office of the Coroner; the Mode of his Appointment and Duties of Taking Inquisitions and Mode of Holding Courts &c To Which are Added Copious Appendices of Useful Precedents.

Jane Austen this book is not. But it is eye-opening.

Who became a coroner? They were all men, of course, and they needed social standing, which meant they had money, property and personal connections. Coroners might be appointed or elected. The counties elected coroners, but upper level-aristocracy, church officials, and, of course, the king, all had the power to appoint coroners. Sometimes coroners had legal experience as a justice of the peace or magistrate, but that wasn’t considered necessary. Neither was medical training of any kind.

The duties of the coroner could overlap other offices. For instance, the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench was also the “principal coroner of England (Impey, pg. 474).”

Each coroner had their own jurisdiction. London had a coroner. So did Westminster. Wales had two for the entire country. The Admiralty had a coroner to cover violent death on the “high seas”, but the ports along the Thames had their own. All these offices were separate from “the Coroner of the Verge,” who was appointed by the Lord Stewart, and was responsible for investigating any violent death that happened on the grounds of one of the royal households. The Coroner of the Verge, however, was different from the Coroner of the Household, who was responsible for investigating any violent death that happened inside the royal residence.

A coroner did not get called to look at every corpse. If the death was assumed to be from natural causes—illness, or a fall, or heart attack—the corner never got involved. I strongly suspect this means a number of domestic crimes went undetected.

If the coroner was called, it could take awhile for him to get to the body. Here we come to another major difference from today. In the early 1800s, forensic science wasn’t even an idea. Nobody was going to leave a body lying around at the scene to wait for the coroner to get there. It was, in fact, taken for granted that the body would be moved. Impey writes:

“…the coroner, upon information shall go to the place where any be slain, or suddenly dead…(he then gathers the locals)…and when they were come thither, the coroner upon the oath of them, shall inquire…, 1. If they know where the person was slain; whether it were in any house, field, bed, tavern or company and who was there.”

So, the coroner would have to ask where the death happened. When the coroner actually saw the body, it could be laid out in the morgue, or in a house, or even in a pub. The Brown Bear public house across the street from the Bow Street police station acted as a de facto morgue, and occasionally a back up prison (J.M. Beattie, The First English Detectives).

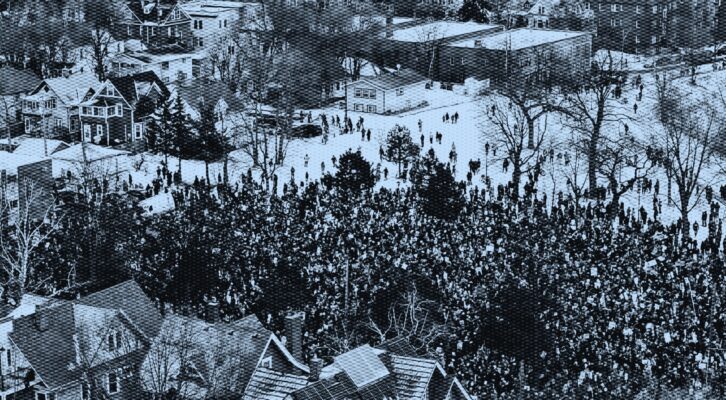

Nobody was going to preserve the scene either. A shop would not close, a house would be cleaned up, the street would be opened again as soon as the body was moved. If the murder happened in London, crowds of neighbors and strangers might be in and out of the house, or pub, or shop before the coroner even got there.

However, physical evidence was not completely ignored. Impey recommends that any and all wounds ought to be viewed and recorded, including where they are, how big they are and what kind of weapon might have been used. I admit, I go a bit further than this in the Rosalind Thorne books. My fictional London coroner, Sir David Royce, is a surgeon, and he does look at the bodies a little more thoroughly than a coroner of the day probably would have.

But physical evidence, when there was any, very much took a back seat to witness testimony. Impey writes:

“Every coroner, upon a view of the dead body, shall inquire of the person that hath done the death or murder; also of their abettors and consenters and who were present when it was done…”

Translation: the coroner asked everybody in the neighborhood who committed the crime and/or who saw it done. It was assumed that the people in the neighborhood would tell the truth because 1) they would want the murderer caught and 2) they would have to swear to what they said. Oaths were considered to be powerfully binding. Lying under oath was a sin and could damn your soul, a fate that only the worst sort of character would risk. Or so it was assumed. It could also, incidentally, land you in jail. If you were caught, of course.

“…it is to be inquired who were culpable…and who were present…An how many sowever be found culpable by inquisition in any of the manners aforesaid, they shall be taken and delivered to the sherriff, and shall be committed to the gaol (sic); such as be founden and be not cuplable, shall be attached until the coming of the justices and their names shall be written in the coroner’s rolls.”

So, if witnesses accused someone of murder or manslaughter, the accused was jailed to await the inquest, and the trial. If the accused could not be found, the locality, and the neighboring localities, would be responsible for mounting a search. Witnesses were told not to leave town (or village, or port). All testimony, along with everybody’s names and their part in the investigation all got written down in “the coroner’s rolls,” which were the official record books. Also, the witness would be shown, or read, a copy of their statement, which they would sign, or at least make a mark on. The coroner would sign it as well.

On the strength of this initial witness testimony, the coroner would decide whether to call a formal inquest. The inquest is where the Regency era murder investigation most begins to resemble its modern counterpart.

First, the coroner assembled a jury. An officer of the court, such as a jury, or a beadle, with official summons to eligible property-owners in the neighborhood. The coroner’s jury would be twelve men (again, always men). The jury would choose a foreman and the members would all be put under oath. The coroner would act as judge and presiding officer. He’d take the jury to have a look at the body, if it was still in good enough shape, and give them any facts about the manner of death that he thought they should hear. After that, they’d return to whatever space was being used as a court room (we could be back at the pub at this point), and the jury would hear from the witnesses.

From here, the proceedings become familiar to those of us in the modern world: Witnesses were sworn in. The coroner would ask the witnesses to repeat their testimony and give the jurors a chance to ask questions. Everything is written down in the official record. The coroner would then sum up the evidence and testimony for the jury. After that “the officer takes them to a convenient room, and attends the door on the outside until they are agreed…”

We don’t know how long it took a coroner’s jury to reach a verdict, but in other legal proceedings deliberation could take all of fifteen minutes, or, if it was a really tricky case, a full hour. If the jury couldn’t reach an agreement, the coroner could poll the jury members, and at decide with the majority.

So, what about the Bow Street runners? Or the other proto-police forces of the time, such as the watch, or the river police? What were their place in the murder inquiry?

Impey does not mention them. Nowhere in over 500 pages, does he document how the coroner could, or would, have any policing officers participate in the inquiry. The officers mentioned are court officers, such as beadles or sheriffs.

However, we do know that Bow Street was engaged to help with murder inquiries. In The First English Detectives, J.M. Beattie finds records of payment for “finding Evidence of a Murder.” Further payments were made for officers helping at the assizes and transporting the prisoners to jail and to trial. But from an official standpoint, the responsibility for the shape, direction and depth of a murder inquiry was entirely the responsibility of the Coroner.

***