Ransom Stoddard: “You’re not going to use the story, Mr. Scott?”

Article continues after advertisementMaxwell Scott: “No, sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

—The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, screenplay by James Warner Bellah and Willis Goldbeck

This line from the film framed how I intended to write a two-fisted tale featuring real life explorer Matthew Henson, a man who, because he was black, didn’t receive the accolades commiserate with his accomplishment (being one of the first to reach the North Pole more than one hundred and ten years ago—April 6, 1909). There had been the so-called autobiography Henson published in 1912, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. Tepid in tone in places, the book was actually more of a memoire of the efforts to reach the Pole than a true rendition of his life, although it does give us some rough outlines.

Henson was an orphan who, like a character in a Dickens’ saga, ran away from a cruel stepmom and signed on at 12 from the docks in Baltimore to be a cabin boy. He would see the wide world; China, Japan, North Africa, and the Black Sea in Southern Russia, among other ports. In the process he learned a seafarer’s navigation and the classics from old sea captain Childs of the merchant ship Katie Hinds.

Congress wasn’t going to give Henson one red cent, let alone a medal.With its focus on servitude rather than adventurous ingenuity, The Negro Explorer can be cringeworthy. In the introduction penned by Booker T. Washington, the famed civil rights leader quoted a correspondence from Commander Robert Peary who headed the North Pole expedition: “Matthew A. Henson, my Negro assistant, has been with me in one capacity or another since my second trip to Nicaragua.” Peary goes on to state, “This position I gave him primarily because of his adaptability and fitness for the work and secondly on account of his loyalty.”

Mind you, Washington gushed in the intro how this demonstrated Henson held a place of honor in the history of the expeditions. Yeah well, post reaching the North Pole, Peary was granted a pension of thousands of dollars by Congress and received a congressional medal. Six times over the ensuing years black leaders pressured politicians to grant such a pension to Henson, noting twice he’d saved Peary’s life in that frozen hell. Six times those efforts died in committee—Congress wasn’t going to give Henson one red cent, let alone a medal.

Henson eventually retired from a clerk job in the Customs House with a pension of $82.27 a month. When he passed in 1955, he was denied a hero’s burial in Arlington National Cemetery, unlike Peary. That is, until the late Harvard neuroscientist Professor S. Allen Counter, something of a Hensonologist, petitioned then President Ronald Reagan to transfer Henson’s remains there. The request was eventually granted, and Henson was reinterred.

For my purposes, I needed to create a full-throated Matthew Henson, one who, we would say these days, had agency, a character in charge of his fate and not subject to the whims and caprice of others. To paraphrase Mr. Scott—from Wild Bill Hickock to the Earp brothers, from Nat Love aka Deadwood Dick, born a slave and becoming a quick draw, bull-dogging, heavy drinking cow-puncher extraordinaire, to jazz age entertainer and spy Josephine Baker—a person of legendary deeds was called for. As matters turned out, even in the real, the ideal could be mined.

Henson learned the Inuit languages when no one else on those expeditions, including Peary, did. The four Polar Eskimos on that historic expedition were men with whom he regularly hung around the campfire, sharing roasted seal; Seeglo, Oqueah, and brothers Ootah and Egingwah. He could skin a musk ox like a champ and was a navigator, master mechanic and sled dog driver.

In The Negro Explorer, Henson wrote, “Naturally there were frequent storms and intense cold, and in regard to the storms of the Arctic regions of North Greenland and Grant Land, the only word I can use to describe them is ‘terrible’ in the fullest meaning it conveys.” This the harsh land where Henson would stare down what he called the Grim Destroyer.

Seems Henson wasn’t quite as much of a turn-the-other-cheek type as was often suggested. In my edition of A Negro Explorer at the North Pole: The Autobiography of Matthew Henson (Invisible Cities Press, 2001), Counter mentions in his introduction the presence of a gentleman from Kentucky named John Verhoeff on one of the attempts to reach the Pole. He freely used the N word when referring to Henson in and out of his presence, and resented Henson and his stature as equal among the other white explorers.

“It is still very curious that days before his departure to the United States, Verhoeff ‘disappeared,’ ” Counter wrote. “Henson and the Inuit all said that they were certain he had fallen through the ice when out for a walk.”

Henson’s personal life, like his professional one, was complicated. Counter’s book North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo, put Henson and Peary on blast. He revealed their Inuit children as neither man had done so in their respective books. The divorced Henson fathered a son named Anaukaq, while the married Peary had two sons, Kali and an older brother also named Anaukaq, who died in his twenties. In the 1980s, Counter brought the surviving sons to the states to be feted when they were in their eighties and grandfathers several times over.

Add in a big dose of strange and you’ve got the perfect recipe for fiction. The best nugget in terms of pulpy goodness potential is the Cape York meteorite; massive pieces of iron space rock Peary and Henson brought back from Northern Greenland further funding their explorations. The alm-nah (woman), her kim-milk (dog), and ahnighito (tent) torn from the sky by the evil spirit Tornarsuk.

This was material from which I could forge a retro-pulp hardscrabble Matthew Henson. Here could be a character set in motion during the Roaring ‘20s, specifically the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance in 1928. Why bring Henson into the ‘20s, decades after his first polar adventures? Partly because the heyday of the pulps was the 1930s with the advent of the Great Depression. New York City was the locale for the Shadow (1931), Doc Savage (1933) and so many others who burst forth from their garish four-color covers to offer readers for a thin dime a “novel-length” bloody thunder quixotic tale of right over super-villain wrong in a time of societal upheaval. But as the Harlem Renaissance was on the wane by then, Henson’s initial fictional outing had to occur a couple of years beforehand so I could set the stage properly.

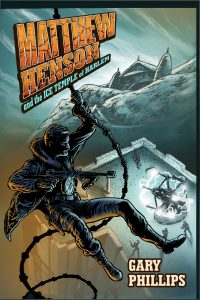

His would be a world of gangsters such as numbers boss Queenie St. Clair, Dutch Schultz looking to muscle her out, and a jackleg spiritualist touting a vision for the oppressed in the vein of Daddy Grace and Father Divine. On top of that, a purported fourth piece of the meteorite is sought by evildoers seeking to mass produce Nikola Tesla’s death ray derived from stolen blueprints. It’s a fragment in the possession of our bold adventurer and the knives are out for him once this is known. America’s first black aviatrix Bessie Coleman also makes the scene to help out her pal Matt (even though in actuality she’d been dead two years from an aviation accident in the time period of the novel). But as every Marvel Comics movie and the recent Watchmen mini-series has shown us, death don’t stop a stepper. For my Mahri-Pahluk, Matthew the Kind One, his smile masks a heart of iron as he faces down the Grim Destroyer in Matthew Henson and the Ice Temple of Harlem.