Who knows what, and how soon will the heroine know everything she needs to know before the encroaching danger finds her? In horror and thriller novels that use multiple points of view to create tension, the heroine is often the last to know.

Sometimes characters possess information they think is unimportant but is actually vital; sometimes characters keep that information to themselves to hide their own sins, much to the detriment of people around them. Very often multiple points of view allow the reader to anticipate a collision approaching between two characters that have no idea their paths about to cross.

Stories with multiple points of view can allow the killer/vampire/monster under the bed/carny with sinister intentions to have their say, for better or worse. The reader knows things the heroine doesn’t, and that knowledge can induce the same agony as spotting Michael Myers’ silhouette behind some hapless babysitter—you know what’s coming, and you’re helpless to stop it, but you yell at the screen all the same, “Run! Run!”

In Natsuo Kirino’s Out, a young mother, Yayoi, murders her abusive husband and enlists the help of her night-shift coworkers—Masako, Yoshie and Kuniko—to hide the body. The point of view swings between the conspirators, each of whom has different motivations for assisting with the crime and differing degrees of ability to handle the pressure of the police investigation. There’s also a frightening sociopath who becomes inextricably bound up in the conspiracy, and as he stalks ever closer to the women the book becomes almost unbearably tense. The reader knows he’s coming, but the women don’t.

Because Kirino chooses to write scenes from the point of view of this sociopath, we know exactly what he has in store for these women when he finds them. As the clock ticks down, the question of escape becomes paramount—will Masako, the coolheaded leader, get away before she’s found by either the police or the killer stalking her?

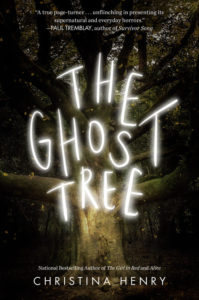

The Ghost Tree, my coming-of-age horror novel about a midwestern town and its inhabitants, features several different point of view characters. Two of the characters have knowledge that nobody else does, knowledge about the mystery at the center of the story. These characters each have different motivations for hiding what they know, even as two other characters, Alex and Lauren, try to discover the why behind what’s happening in their town. One character is an outsider that could uncover things better kept hidden. One character is a mother just trying to figure out what’s happening to her children. Each person brings a fresh perspective to the mysterious happenings in the town of Smiths Hollow.

The genesis of this book came from a single sentence that I wrote in my notebook in 2016—“Meet me by the old ghost tree.” I wrote this book as an homage to all the coming-of-age horror novels I loved when I was younger, and to that end I play around with those horror tropes in the book.

Stephen King and Ray Bradbury wrote lovingly of the times of their childhood in their novels, and in The Ghost Tree there’s a small town nostalgically drawn from the era of my youth (in my case, the 1980’s). There’s a sinister conspiracy, a curse, unexplained disappearances and deaths, a policeman determined to find the answers, a child who knows things he shouldn’t and that bigoted old lady that everyone hates who lives at the end of the block.

But there’s also something that was missing from so many of those coming-of-age books that I loved—girls. Girl voices, girl perspectives, girl relationships. Lauren and Miranda are the heart of the book, and the changing nature of their childhood friendship reflects the struggles that so many girls have as they grow older and grow apart from the person they thought was their best friend forever.

Writing point-of-view scenes from both Miranda and Lauren shows the different perspectives they each have on their friendship, as well as the ways they each brush up against the danger present in their town. Their relationship is straining at the seams. When one person gains information that isn’t shared with the other, this puts both of them at risk.

In Paul Tremblay’s Disappearance At Devil’s Rock, thirteen-year-old Tommy goes missing. Tommy’s friends, Josh and Luis, claim not to know exactly what happened to him, and a massive search begins. Tension is created from the start, as Tommy’s mother Kate tries to discover what happened to her son.

Her search is interspersed with Tommy’s journal entries, which allow the missing boy a presence in the story he wouldn’t otherwise have, and scenes from Tommy’s sister, Kate, which offers another layer of perspective on the family and the terror of searching for a missing loved one. The inclusion of Tommy’s journal entries, in particular, is an inspired choice that gives a voice to a character who is physically missing from the story.

Other characters—the detective investigating the case, the boys who last saw Tommy—contribute to the suspense as they uncover new information or reveal what they know. Josh and Luis, in particular, seem to reluctant to tell the police exactly what happened, and the reader becomes desperate to hear their whole story in the same way that Kate does.

A story told from one point of view necessarily limits the reader’s knowledge to what the protagonist knows, and this can certainly generate suspense as the reader uncovers the mystery alongside the main character. Widening the lens can allow the story to be viewed like a mixed-up Rubik’s cube—there are many sides, and the colors are out of alignment. As the story draws towards its climax, the colors start aligning in a meaningful way, and the reader (and protagonist) starts seeing patterns that weren’t there before. Suddenly, almost as if by magic, the individual points-of view—the cubes—line up and the puzzle is complete.

***