Writing a good crime novel is difficult, soulful work. These books we love take on some of humanity’s darkest moments, looking for answers, meaning, or just the catharsis of a full recording. Yes, there are pillars of the form—the disappearance, the sleuth, the colorful side characters and suspects, the insistent search for truth. But there’s no magic formula, no instruction guide that can take you chapter by chapter through writing a successful mystery. There is, however, the wisdom of the greats. From Christie to Chandler to the modern-day masters, many of our favorite authors have turned their attention to the craft of the mystery novel. Scouring the books, interviews, letters, and articles of these icons, we’ve assembled a handy guide to writing a great crime/mystery novel. Some of the advice is easier said than followed; other times the ideas are downright contradictory. Take the wisdom in doses, chew it all over and use what works for you. Above all, keep on writing mysteries and we’ll promise to keep on reading them.

GETTING STARTED

Don’t fret about outlines. Don’t over-plan.

“The plans for a detective novel in the making are less like blueprints than like travel notes set down as you once revisited a city. The city had changed since you saw it last. It keeps changing around you. Some of the people you knew there have changed their names. Some of them wear disguises.”

–Ross Macdonald, On Crime Writing (1973)

“At the time I begin writing a novel, the last thing I want to do is follow a plot outline. To know too much at the start takes the pleasure out of discovering what the book is about.”

–Elmore Leonard, “Making It Up As I Go Along,” AARP Magazine, (2009)

Remember, you’re never too old to start, although you may be too young.

“A lot of novelists start late—Conrad, Pirandello, even Mark Twain. When you’re young, chess is all right, and music and poetry. But novel-writing is something else. It has to be learned, but it can’t be taught. This bunkum and stinkum of college creative-writing courses! The academics don’t know that the only thing you can do for someone who wants to write is to buy him a typewriter.”

–James M. Cain, “The Art of Fiction No. 69,” The Paris Review (1978)

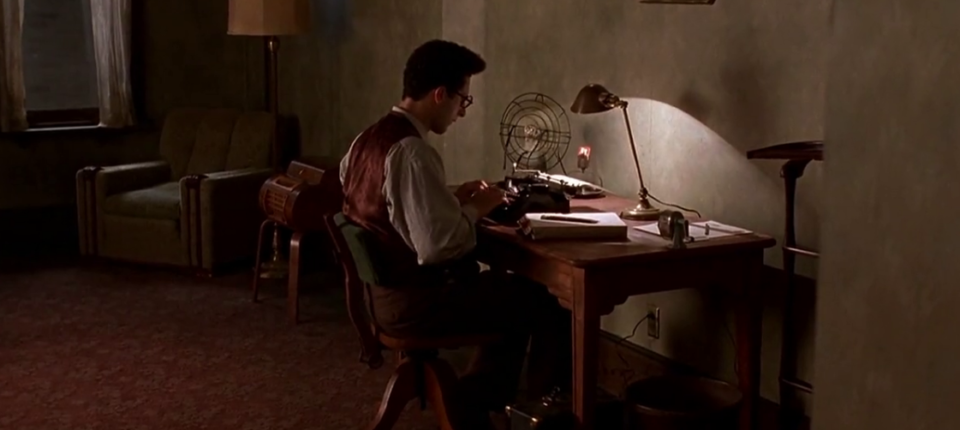

Arrange your surroundings. Prepare for contingencies.

“In my hotel room in Paris I only needed cigarettes, a bottle of scotch, and occasionally a good dish of meat and vegetables cooking on the burner behind me. Writing’s always whetted my appetite.”

–Chester Himes, Interview with Michel Fabre (1983)

FINDING A STORY

Look for a story that would keep a child entertained on a rainy day.

“The writer is like a person trying to entertain a listless child on a rainy afternoon. You set up a card table, and you lay out pieces of cardboard, construction paper, scissors, paste, crayons. You draw a rectangle and you construct a very colorful little fowl and stick it in the foreground, and you say, ‘This is a chicken.’ You cut out a red square and put it in the background and say, ‘This is a barn.’ You construct a bright yellow truck and put it in the background on the other side of the frame and say, ‘This is a speeding truck. Is the chicken going to get out of the way in time? Now you finish the picture.'”

–John D. MacDonald, The Writer (1974)

Collision is good, and retribution is even better.

“The cat sat on the mat is not a story; the cat sat on the dog’s mat is the beginning of an exciting story, and out of that collision, perhaps, there comes a sense of retribution. Now you may call that God, or you may call it the presence of fatalistic forces in society, or you may call it man’s inhumanity to man. But, in the immortal words of P.G. Wodehouse, what it boils down to is that if your character does something wrong, sooner or later if he walks down a dark street, fate will slip out with a stuffed eel-skin and get him.”

–John Le Carré, “The Writer Who Came in from the Cold,” BBC/Michael Dean (1974)

THE CHARACTERS

Make your characters worth saving, whether you save them or not.

“The more passionately alive the victim, the more glorious indignation I have on his behalf, and am full of delighted triumph when I have delivered a near-victim out of the valley of the shadow of death.”

–Agatha Christie, An Autobiography (1977, posthumous)

Give every character a dose of humanity.

“A man once asked me … how I managed in my books to write such natural conversation between men when they were by themselves. Was I, by any chance, a member of a large, mixed family with a lot of male friends?…I replied that I had coped with this difficult problem by making my men talk, as far as possible, like ordinary human beings. This aspect of the matter seemed to surprise the other speaker; he said no more, but took it away to chew it over. One of these days it may quite likely occur to him that women, as well as men, when left to themselves, talk very much like human beings also.”

–Dorothy L. Sayers, Are Women Human? Astute and Witty Essays on the Role of Women in Society

THE SETTING

A good setting may be the spark your story needs

“Something always sparks off a novel, of course. With me, it’s always the setting. I think I have a strong response to what I think of as the ‘spirit of a place.’ I remember I was looking for an idea in East Anglia and standing on a very lonely stretch of beach. I shut my eyes and listened to the sound of the waves breaking over the pebble shore. Then I opened them and turned from looking at the dangerous and cold North Sea to look up and there, overshadowing this lonely stretch of beach was the great, empty, huge white outline of Sizewell nuclear power station. In that moment I knew I had a novel.”

–PD James, “PD James’ 10 Tips for Writing Novels,” BBC (2013)

THE ACTION

Hold onto the mood with as little as possible.

“To say little and convey much, to break the mood of the scene with some completely irrelevant wisecrack without entirely losing the mood—these small things for me stand in lieu of accomplishment. My theory of fiction writing … is that the objective method has hardly been scratched, that if you know how to use it you can tell more in a paragraph than the probing writers can tell in a chapter.”

–Raymond Chandler, June 1949 letter to his UK publisher, Hamish Hamilton

Forget set pieces and focus on dialogue and concrete description.

“I may satisfy myself with Richard II or a crime novel and tell all the fancy boys to go to hell, all the subtle-subtle ones that they did us a service by exposing the truth that subtlety is only a technique, and a weak technique at that…all the editorial novelists that they should go back to school and stay there until they can make a story come alive with nothing but dialogue and concrete description: oh, we’ll allow them one chapter of set-piece writing per book, even two, but no more; and finally all the clever-clever darlings with the fluty voices that cleverness, like perhaps strawberries, is a perishable commodity…The test of a writer is whether you want to read him again years after he should by the rules be dated.”

–Raymond Chandler, September 1947 letter to his agent, Helga Greene

Forget about good taste and focus on what the world is really like.

“Many times I’ve been told by people I respect, ‘There’s too much emphasis on race in this book,’ or ‘The government and the police aren’t really like that.’ I am asked not to stand down but to stand back—behind the line of good taste. ‘Books are entertainments,’ I am told. ‘No one wants to hear your ideas about how the world works or what’s wrong with America.’ Of course they don’t. The job of the writer is to take a close and uncomfortable look at the world they inhabit, the world we all inhabit, and the job of the novel is to make the corpse stink.”

–Walter Mosley, “The Writing Life,” Washington Post (2005)

REVISION AND EDITING

Cut everything you possibly can, then cut four pages more.

“For all your cutting, there is usually more to come. Cutting becomes more and more painful, more and more difficult. At last you don’t see a single sentence anywhere that can be cut, and then you must say, “Four more whole pages have got to come out of this thing,” and begin again on page one with perhaps a different colored pencil or crayon in hand to make the recounting easier, and be as ruthless as if you were throwing excess baggage, even fuel, out of an overloaded airplane.”

–Patricia Highsmith, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966)

Identify your favorite sentences and then cut them.

“Just one piece of general advice from a writer has been very useful to me. It was from Colette. I was writing short stories for Le Matin, and Colette was literary editor at that time. I remember I gave her two short stories and she returned them and I tried again and tried again. Finally she said, ‘Look, it is too literary, always too literary.’ So I followed her advice. It’s what I do when I write, the main job when I rewrite…Adjectives, adverbs, and every word which is there just to make an effect. Every sentence which is there just for the sentence. You know, you have a beautiful sentence—cut it. Every time I find such a thing in one of my novels it is to be cut.”

–Georges Simenon, “The Art of Fiction No. 9,” The Paris Review (1955)

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

–Elmore Leonard, “Easy on the Adverbs, Exclamation Points and Especially Hooptedoodle,” New York Times (2001)