Noir is alive and well and probably will never die (despite the fact that most people of my acquaintance don’t seem to know what it is when I share that I’ve written a feminist noir). When I’m asked to explain noir, too often I fall back on that old pornographic clarification: “I know it when I see it.” But the truth is, noir has traditionally rested heavily on the value of familiar tropes (as does any genre deeply entrenched and well known) and that familiar ground is what makes noir so immediately recognizable—as well as so easy to get wrong, or make stale.

Those tropes are both a challenge and an opportunity for writers: there’s so many ways to become a cliche, low rent Raymond Chandler, and also so many opportunities to remake something out of the familiar into something new.

In my debut novel, The Lady Upstairs, I wanted to take one of those most familiar of noir tropes—the femme fatale—and flip the lens so that she got to take center stage in a story. That meant expanding her into a full character, with a full spread of feeling not usually given to the femme fatale in traditional noir literature. But that’s not to say that I didn’t have plenty of examples to lean on for ways to update the noir traditions.

From Vicki Hendricks to Tod Goldberg, here are examples of writers who took on noir tropes, and reinvigorated them in new, surprising, and totally fresh ways.

Chewy language.

You can spot any writer who has read too much Raymond Chandler because he’s usually trying to unsuccessfully channel Chandler’s gorgeously bonkers metaphors and similes (the famous “tarantula on a slice of angel food” comes to mind). But a writer who has mastered the chewy language that makes you slow down and truly savor a page, Chandler-style, without in any way imitating Chandler, is Megan Abbott.

Megan Abbott’s early novels, including my personal favorite, Queenpin, are noir classic throwbacks, given a feminist and female-centered slant. And throughout, her gorgeous, sharp, breathtaking language is gorgeously on display. Chandler would be green as a goblin with jealousy.

First person narration/the monologue of a body.

There’s two different versions of this trope: in fiction, it’s the first-person point of view narration that provides a specific (and limited) look through one character’s eyes. A variation of this occurs in noir film: the first-person monologue of the dead body to set up the story (famously used in Sunset Boulevard).

Rachel Howzell Hall finds an ingenious way to play with both tropes in They All Fall Down, her sharp and modern take on Agatha Christie. By setting the earliest pages with a monologue from first-person narrator Miriam Macy, who may or may not by dying on a beach in Mexico, the reader is pulled immediately into the mystery of whether she’ll live or die…and how she ended up there in the first place.

Private investigators.

Speaking of Chandler, the man wrote an entire treatise on the type of man who would make the ideal private investigator. The gumshoe must be a man inside the world of crime, but not a part of it; the best man of his own world and a good enough man in any world, among other criteria.

One could assume that Chandler probably meant his treatise to cover the bases of the criteria required for a good fictional private dick to encompass more than one gender. But Steph Cha’s reimagining of a modern iteration of Phillip Marlowe in Los Angeles-based, Korean-American, female Jupiter Song fits the mold and breaks it. Song stalks the streets of Los Angeles in six inch heels, using her love of Marlowe, her wits, and her moral compass to follow the labyrinthine truth at the heart of each mystery she encounters—even when (especially when) finding that truth will break her heart. A good enough woman for any world.

Hardboiled detective/protagonist.

They don’t make ‘em much more hardboiled than Dashiell Hammett’s The Continental Op, but a hardboiled protagonist is a classic hallmark of noir. The hardboiled protagonist is a staple: a cynicism that conceals a heart that feels too much, a pessimistic view of the world that often curdles into antiheroism.

I first encountered Tod Goldberg’s novels about hitman-turned-rabbi Sal Cupertine at a Noir at the Bar reading in Los Angeles. I was struck immediately by the premise (a mob hitman hides out in Las Vegas as a rabbi following a botched hit in Chicago) and by Goldberg’s sharp and witty Elmore Leonard-esque writing, but as I delved deeper into the books (Gangsterland and Gangster Nation are both currently available and highly recommended), I came to appreciate even more the character evolution of Sal. At the start of the series, Sal is just about as hardboiled as they come: a mob-connected hitman who doesn’t think twice about committing a hit for his 9-5. But as Sal transitions into Rabbi David Cohen, his viewpoint begins to evolve and become more expansive and complicated as he reckons with his newfound moral compass.

Femme/homme fatale.

If you know noir, you know the femme fatale: she’s got the best lines, she’s got the best wardrobe, she’s trouble and she’s danger and she’s a lot of fun. (For noir films, she’s often front and center on the poster.) For classics, no one does the femme fatale better than James M. Cain: desire as destructive force drives the engine of two noir classics, both The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, novels that punch above their weight in terms of impact per number of pages.

But her less well-known counterpart, the homme fatale, can be just as enticing a figure, and capable of causing as much destruction in his wake. In Vicki Hendricks’ novels Miami Purity and Iguana Love, it’s hommes fatale who lead our heroines astray. Both Sherri Parlay and Ramona Romano are so tuned into their sexuality that it winds up being a deadly and destructive force in their lives, to men as dangerous as any soft-curved dame Cain thought up.

Addiction.

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that a noir protagonist helming a story is probably in search of a drink (or a fix). In classic and neo-noir alike, our tarnished protagonist often leans on substances to cope with an irreparably corrupt world. And often, the decision of whether or not to give into that vice is a central question circling the character throughout a series.

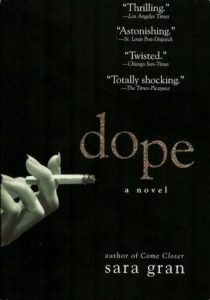

In Sara Gran’s noir gem of a novel Dope, our protagonist, Jo, is trying her damnedest not to fix. In 1950, Jo is a recovering dope addict hired by a couple to find their daughter, also an addict, who has gone missing somewhere in New York City. The realism of Gran’s character’s addiction and struggle to stay clean, even as she delves back into the streets and relationships that once lead her astray, heightens the stakes and leads to an ending as perfectly pitch-black and devastating as any noir novel I’ve ever read.

***