Quite how Ian Fleming got to Portugal in June 1940 is unclear. To have gone overland would have been extremely unlikely, and as his objective was to get to Madrid if going overland, why go to Portugal? He could have gone by sea, but he would have had to obtain a visa from the Portuguese Consul in Bordeaux. These were freely obtainable, thousands being issued by the consul, Aristides de Sousa Mendes. However, most people traveled by land and the influx was so great that it led to the Spanish closing the border with France, and an increase in tension between Lisbon and Madrid. Sousa Mendes paid for this humanitarian act with his career and the ruin of his family by a furious Dr. Antonio De Oliveira Salazar, dictator of Portugal.

Could Ian have taken a flight from Bordeaux? Two weeks before, Sir Samuel Hoare flew south with his wife to take up his post as ambassador in Madrid. His aircraft had refueled at Bordeaux, where he found the “aerodrome was nominally still in use.” His flight was going via Lisbon and would be the last civilian one to leave Bordeaux. He recalled, “Our arrival created little interest amongst the handful of employees who were still on the aerodrome and it was with a feeling of foreboding that having lunched, we quitted France.” Hoare, a nervous man, was not looking forward to taking up his new post in Madrid.

John Pearson, in his book The Life of Ian Fleming, claims that Fleming returned to England by sea first: “HMS Arethusa was waiting off Arcachon to take away the British Ambassador and when she sailed Lieutenant Commander Fleming would sail in her.”

This is maybe more likely as Fleming could then have got a flight to Lisbon; on June 4, BOAC started operating a service from Heston aerodrome, west of London, to the Portuguese capital. In the Spanish capital events had taken a turn for the worse for Britain. The Franco regime had changed the war status of Spain from “neutrality” to an undefined “nonbelligerence,” which showed a clear sympathy for the Axis. On June 10, Mussolini’s Italy had entered the war and many expected Spain to follow suit.

***

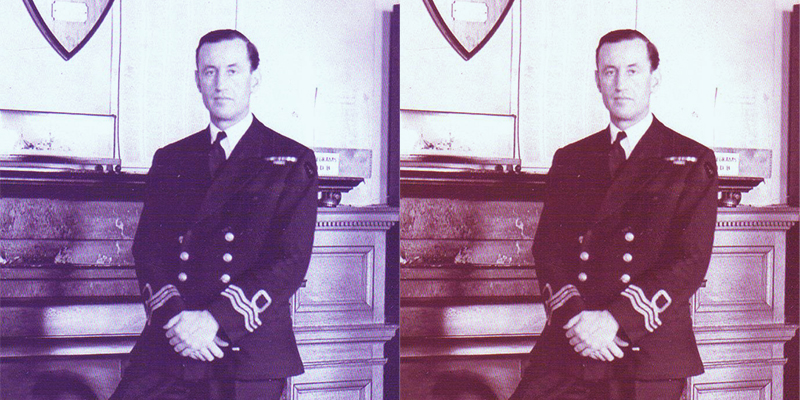

In June 1940, Alan Hillgarth was forty-one years old, nearly ten years older than Fleming, a handsome man with an olive complexion and dark flashing eyes. Aged twelve, he had been sent to Osborne College on the Isle of Wight in preparation to join the Royal Navy, where he had been nicknamed “the little dago.” He served through the First World War, mainly in the Mediterranean. It was in the Navy that he started writing, his first story being published in Sketch magazine in July 1918. In 1922, after eight years’ service, Alan was placed on the retired list at his own request. He did not have the burning ambition to stay in the Navy. In 1923 he commuted his annual pension of £97 for a one-off sum of £1,370. He then took up his pen to earn a living as a writer and traveled a lot.

Two years after leaving the Navy he changed his given name of George Hugh Jocelyn Evans to Alan Hillgarth, having first used it as a nom de plume in his writing.

In 1930 Hillgarth married the divorcee Mary Hope-Morley and they moved to Majorca. None of his adventure novels sold particularly well. He did sell the film rights of The Black Mountain to an American company for $5,000 but it was never made. In 1932 he was appointed acting “vice consul” in Palma by the British government.

Godfrey and Alan met in 1938 when Repulse visited Majorca. They found they had much in common, having both served in the Gallipoli campaign as junior officers. Godfrey had a mission to visit the British Legation near Barcelona. This was during the height of the Spanish Civil War and he was worried his ship might get caught up in Italian air raids. However, Hillgarth, through his contacts within the Spanish Command and Italian Air Force, obtained an agreement that no raids would be conducted in the area during Repulse’s visit. Godfrey was impressed and called it an outstanding feat “in practical diplomacy.” In August 1939, instigated by Godfrey, Hillgarth took up the post of naval attaché in Madrid and was recalled to the Navy’s active list.

***

The enemy Alan Hillgarth faced in Spain in the early months of the war was powerful and well established. The shrewd head of Abwehr, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, knew Spain well, having served there in the First World War, and since 1937 had built up several stations on the Iberian Peninsula. Running a large number of agents and contacts, the Abwehr enjoyed another advantage of being able to work closely with the Spanish Secret Service, the Sirene, run by General Martinez Campos, another old friend of Canaris.

Ian Fleming stayed with the Hillgarths in Madrid. He and Alan then went by road to Gibraltar, taking Mary along with them to give the outing the cover of a sightseeing trip, although they flew a White Ensign from the car’s aerial. Mary was not impressed with Ian as an NI officer, as he left his wallet behind at a restaurant, but she found him amusing.

Their main aim from the trip was to lay the foundations of a stay-behind sabotage and intelligence-gathering operation within the Iberian Peninsula, in case the Germans invaded, and also to establish an NI office in Gibraltar. On the way they met Colonel William Donovan, the United States intelligence chief, who was on a fact-finding visit to Europe. They briefed him on the vital efforts being made to keep Spain neutral. From Gibraltar Ian went on to Tangier to create a haven there in the event the Rock should fall.

Back at his desk in London by August, Ian began work on the stay-behind operation for Spain and Gibraltar should the Germans move in. So, where did the name Golden Eye come from? Fleming would later name his Jamaican home Goldeneye, after all. It seems likely that at the time he was reading the Carson McCuller novel Reflections in a Golden Eye. Maybe the name, in some way, reminded him of Spain. The novel was not published until 1941 by Houghton & Mifflin but was serialized in the October–November issue of Harper’s Bazaar magazine and likely advertised in the August–September issue.

Soon after returning, Fleming wrote to Hillgarth, thanking him and Mary for their hospitality and kindness to him and praising Alan’s excellent work as naval attaché in Madrid. He added that NI was fortunate to have such a strong team “in our last European strong hold,” resulting in the “great contribution you are making to winning the war.” Later in the same letter he turned to Golden Eye:

4) You will by now have a signal about receiving Golden Eye messages. Mason Macfarlane [Lt-General Noel Mason-Macfarlane Governor of Gibraltar] has no objection, and C.N.S [Commander Naval Station] is about to give his decision, which I have no doubt will be favorable.

He concluded with Portugal:

7) I discussed the inclusion of Portugal in Golden Eye on my way through Lisbon, and got the Naval Attaché’s reaction on a very general plane. This has been put up to the Planners, and I have no doubt that the answer will be “yes” and that Owen will be instructed to go down to Gibraltar to report to the delegation.

There was a lot involved in the planning of Golden Eye at a time when Ian had many calls on his time. For a start, the operation had to be sub-divided into two plans: Operation Sprinkler to assist the Spanish if they resisted a German invasion and Operation Sconce if the Spanish cooperated with the Germans. Both would mean that Section H of the newly formed SOE would deploy sabotage teams using Spanish guerrillas to hit transport links and fuel stores. Selected members of these teams started training in the highlands of Scotland at a converted farmhouse in Camusdarach near Inverness in December 1940. One report commented that, “the most striking thing about the Spanish troops is their pride in being members of the British Army, and also their gratitude for the work that has been done in this country on their behalf.”

Ian was no doubt glad to head for Spain again in February 1941 to review Golden Eye on the ground. He would be happy to get away from his desk, and the bickering between the SIS and SOE over the operation, but also to get away from the Luftwaffe bombs. In the Blitz he managed to survive three buildings that were badly damaged. One was the Carlton Hotel, where he stayed because the skylights at his flat at 22 Ebury Street could not easily be blacked out so he had to find temporary accommodation. Here his third-floor room was destroyed by a bomb. Ian helped rescue a waiter and maid who had been buried under the wreckage. Later he went to sleep with the other residents in the grill room.

On February 16, Ian flew out to Lisbon and then to Madrid, where he was issued with a courier’s passport from the embassy dated the same day. It was issued in order to ease his travel between the Rock and Madrid. He carried a commando fighting knife, which he bought from Wilkinsons and carried on his foreign assignments. It was engraved with his name and rank on the blade. His fascination with gadgets extended to a fountain pen that could be fitted with a cyanide or tear gas cartridge, which he carried as well. He was fully prepared to explore his fantasies of life as a secret agent.

Fleming equips his hero Bond with a Swaine Adeney “slim, expensive-looking attaché case,” to take to Istanbul in From Russia with Love, full of secret agent goodies. It contains “50 rounds of .25 ammunition” for his Beretta, while his Palmolive shaving cream tube houses the silencer.

*

Accommodation, hospitals, storage caves, water, and sanitary arrangements were built into a vast network of tunnels and chambers running the length of the Rock. In all there would be thirty-four miles of tunnels, most of which were finished by 1943. The work was carried out by four companies of Royal Engineers and a Canadian tunneling firm that had perfected a diamond drill blast method, a new drilling technique that saved a lot of manual labor.

This clearly had an influence on Fleming’s later writing. In Dr. No, Bond and Honeychile Rider are imprisoned by Dr. Julius No in a warren of rooms built into the “side of the mountain” on Crab Key, the island that ended in a “cliff face.” The walls of the corridors were moisture free, and “the air was cool and pure with a strongest breeze coming toward them. A lot of money and good engineering had gone into the job.”

At Gibraltar, Ian set up a Golden Eye liaison office with its own cipher link. It was to consist of a team of ten naval personnel led by a commander, and including demolition officers and a petty officer telegraphist. However, if Spain succumbed to German entreaties to join the war or was invaded, it was unlikely Britain would be able to hold Gibraltar. To be able to continue monitoring Allied shipping in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic another back-up office was set up in Tangier and commanded by Henry Greenleaves.

On June 14, 1940, Spain had occupied the international zone of Tangier on the pretext of guaranteeing its neutrality. This, however, was a ploy as Franco dreamed of annexing the whole of Morocco. At the time, the city of Tangier was a hotbed of agents from both sides. The Abwehr had established offices there. It was only two and a half hours by boat across the straits to Spain, seven hours by road from Casablanca, and three hours on a flight from Lisbon.

The old town with its Grand Socco market square was called the Medina, and was made up of narrow streets that no traffic could enter. Ian Fleming enjoyed a night on the town with Henry Greenleaves there and the heady atmosphere for him was like a tonic. The mysterious Mr. Greenleaves does emerge in the Admiralty files in his report to Commander G. H. Birley at Gibraltar dated April 17, 1941, on his work in Tangier, which Birley passed on to Godfrey. In it, Birley summed up, “Finally I wish to report that I am more than satisfied with Mr. Greenleaves’ activities; he mixes well; is a popular member of the community and has enough private means to entertain judiciously.” The drinking antics of Fleming and Greenleaves would become famous in NID; is this a Felix Leiter-type character who like Bond was fond of his hard liquor? “Better have one last Bourbon and branch-water,” he tells Bond before he heads for Las Vegas in Diamonds are Forever, when they have already consumed a huge quantity.

Fleming’s work would seem to have brought tangible results, which must have been a fillip for him, for even in the short time he was there he learned that General Erwin Rommel had arrived in Tripoli, Libya, to command the newly formed Afrika Korps.

The British Consul to Tangier, the straight-laced former Guardsman Major Alvary Trench-Gascoigne, had been in the post for less than a year. He is likely not to have been too impressed with his new attaché, or the visiting NID officer, for carousing around the town. After all, he already had enough on his plate. Despite his protests, Franco had allowed the German Consulate, closed since 1914, to reopen. The consulate became a large legation on the site of the Mendoub’s palace that was to run a serious espionage center for the next three years. In the report Fleming sent to Godfrey he noted, “Although H. M. Consul-General [Trench-Gascoigne] and Greenleaves are on friendly terms, the former still cannot, I think, rid himself of the feeling that Greenleaves is an interloper.” This state of affairs was not helped by “the fact that Greenleaves and the SIS do not get on well together whereas H. M. Consul-General has implicit faith in SIS.” In an earlier report by Greenleaves to Birley he had noted in regard to SIS, “On your instructions, I shall have no further contact with this Department.”

In Madrid, Hillgarth and Fleming held final discussions on Golden Eye before Ian returned to London. There was likely a rift between the two men, who did not agree on the best way of going forward with it. Hillgarth was beginning to sense that there were too many people involved, and was concerned about the wisdom of sending so many agents from the SOE, then known as SO2, from the sabotage section of SIS, into the country, where they were colluding with the left in Spain. He referred to this as “dangerous, amateurish activities.” Fleming also had reservations, confiding to Dykes that he believed SIS and SO2 were on course for a “crash-out.”

In April, Ian wrote a report on “divisions of interests between SIS & SO2 (SOE).” He observed that since the creation of SO2 “as a separate entity, charged with sabotage in enemy countries, SO2 and SIS have been in competition.” In Spain he felt the attempts by SO2 to form a “sabotage organization” had left the naval attaché trying to direct these operations “compromised to a certain degree.”

Yet in January only a few weeks before, Hillgarth had been in London and met with Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare and head of SOE, who told the prime minister that Hillgarth “has consented to supervise the whole of our activities in Spain.” Godfrey was not happy with his star attaché being compromised and wrote to the chiefs of staff in April that “intelligence is of primary importance” and SIS should be given precedence and have the right of “veto” over SO2 projects.

Hillgarth tried to smooth things over with Godfrey, and even tried to persuade Hoare, the British Consul in Madrid, who was dead set against any cloak and dagger business, that SO2 [SOE] could do important work in preparation for a German invasion “provided they were rigidly controlled.” He later wrote a report on “The role of the Naval Attaché,” as he felt he had had to create a sort of “substitute SIS in Spain.” He explained that this would not cause trouble because “a) my reports were to both DNI and CSS and b) my relations with SIS in Madrid were first class.”

*

Two incidents with SIS caused alarm within the British Embassy Madrid and created more work for Hillgarth. The first centered on Paul Lewis Claire, a French naval officer, who transferred to the Royal Navy after France fell. He was taken on by SIS O Section to land agents in France by sea. On July 23, he was in the Vichy Embassy in Madrid revealing SIS secrets to the naval attaché. This news reached Hoare, who requested immediate instructions from SIS as Claire was expected at the British Embassy the next day to pick up his passport. Frank Slocum at SIS advised that Hillgarth should take “what steps he can to intercept Claire.” He also suggested that SOE might “liquidate Claire” and even thought about kidnapping Claire’s wife in an attempt to bring him to heel. Colonel Stewart Menzies “C” of SIS was in favor of capture.

Leonard Hamilton Stokes, head of SIS Madrid section, and Hillgarth lured Claire to the embassy, where he was beaten up and drugged with morphine. He was then bundled into a car and they set off for Gibraltar, with instructions that under no circumstances should he be allowed to escape.

On the long journey south, Claire began to regain consciousness and called for help in a Spanish village. To keep him quiet, he was hit over the head with a pistol, but the blow proved too hard and he died. The message from the SIS agent in Gibraltar read that the “consignment arrived in this town completely destroyed owing to over attention in transit” and would be disposed of. Hoare claimed in Madrid “once again we here have had to save SIS from catastrophe,” rather ignoring that Hamilton Stokes was an SIS officer.

However, Claire was hardly dispatched with the calm skill of 007 when the need had arisen, such as when Bond deals with the Mexican Bandit at the start of Goldfinger, and then “looked down at the weapon that had done it. The cutting edge of his right hand was red and swollen.” He keeps exercising the hand on a plane so that it will heal “quickly” as “one couldn’t tell how soon the weapon would be needed again.”

There were protests from the Spanish Foreign Ministry after Vichy France broadcast on the radio about the affair. Two days later, the London Daily Telegraph hit back with the headline “Nazis Invent Kidnapping.” Later, Fleming informed the Red Cross that Claire was “missing believed drowned” while on board the SS Empire Hurst, which had been sunk by enemy aircraft on August 11, 1941. After the war, to protect SIS, Claire’s widow was paid a pension.

The second incident to cause alarm was that of Lieutenant Colonel Dudley Wrangel Clarke. In this case, Hillgarth had to retrieve him out of a Spanish jail after he had been arrested in drag.

Clarke was the head of the deception unit in Cairo at GHQ Middle East. He traveled to Lisbon, then Madrid, his cover being a war correspondent for The Times. He was actually there to develop contacts to help his department with the assistance of SIS. He saw Hamilton Stokes at the embassy on October 17, 1941, and the next day he was arrested by the Spanish Police in a main street dressed as a woman, brassiere and all. He told the police he was a novelist trying to get under the skin of a female character. Then he told Hillgarth that he was taking the garments to a lady friend in Gibraltar, despite the fact that the clothes all fitted him, including the high-heel shoes. Later he maintained it was a ploy to see if his cover could hold with the Spanish and Germans.

When the risk of German invasion in the spring of 1941 seemed likely, Hillgarth visited Gibraltar to check all was in order. He found to his fury that when the mission moved to Spain, Brigadier Bill Torr, the military attaché, would command it. He wrote to Godfrey in anger: “I am not quite clear what I’m to be or do—either just a lackey to the Ambassador and separated from the mission or a sort of glorified interpreter… Please take me away out of it to another job where I can be of some use.” Godfrey quickly intervened to promote Hillgarth to the dormant rank of commodore and designated him as the Chief British Liaison Officer. Godfrey wrote to him that he had spoken to the prime minister about Golden Eye and that the operation was still under review. He assured him that he had put forward proposals that were in “accordance with your wishes and in accordance with the recommendations which Fleming brought back from Spain and of which I know you are aware.”

Godfrey thought that Hillgarth had written his letter “rather hastily” and assured Hillgarth that he had his “best interests in mind and that I appreciate your services in Spain sufficiently to make every effort to protect your future status against incursions from whatever quarter.”

Later that year Hillgarth wrote a report on Golden Eye to argue that the “fact that no invasion has yet taken place does not justify any relaxation. I feel however that the original plan from a naval point of view was unnecessarily ambitious.”

It was, of course, Fleming’s original plan, but Admiral Godfrey was happy with his work. On his return to London, Ian was tight-lipped about the trip, though he did tell Maud Russell, who worked in NI, that “he had enjoyed the spring almond blossom in Seville.”

In a letter to Hillgarth, he commended him: “It is lucky that we have such a team in our last European stronghold and results have already shown the great contribution you are all making toward winning the war.” He also promised Hillgarth some Henry Clay cigars, which he begged him to smoke himself “and not give them to [his] rascally friends.”

__________________________________