Growing up poor in the rural Midwest in the ’80s, I never saw my life reflected in pop culture. A staggering number of sitcoms took place in mansions, boarding schools, and penthouses. Movies were set in affluent Chicago suburbs or sunny California subdivisions. Roseanne came the closest to familiarity—a working class family with ugly furniture and real-world problems—but if you wanted a gritty rural tale, with kids in home-sewn clothes scraping by in the middle of nowhere, you were out of luck.

Books were no better. Most novels from my home state of Missouri were a hundred years old, classics like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Shepherd of the Hills, and anything set in a small town tended toward the idyllic. There was no library where I lived, so it was difficult to get my hands on anything contemporary.

While I loved escaping my own environment to live vicariously through the page and screen (I fantasized about living in a suburb, in a house with plush carpeting), I sometimes wondered why I didn’t see a world like mine, a landscape of rusted trailers and hand-me-downs and deer carcasses hanging from trees. There were no neighbors toting shotguns and living off the land in primetime, no families entrenched in rural poverty, struggling to get by. We were largely excluded from popular culture. I felt isolated, as though my experience wasn’t interesting enough or important enough—or entertaining enough—to show the outside world.

Yet those were the only stories I knew, and the stories I wanted to tell. I was endlessly fascinated by the Ozarks, my childhood home. The place held a darkness for me, the rugged and beautiful landscape filled with foreboding, the close-knit communities bound together by complex webs of blood and loyalty, by generations of shared history and survival. Bitter and bare-boned as my life could be, there was plenty of fuel for the imagination. I wrote the stories I wanted to read. They all centered around terrible, small-town crimes.

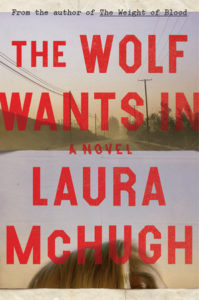

Unbeknownst to me, Daniel Woodrell was starting his career the next county over. Years later, while writing my first novel, The Weight of Blood, I would discover his work. It was exhilarating to find a living author writing so beautifully about dark deeds in the hills and hollers of my home. I’d been waiting all my life for such a thing. I wondered if there was any point in finishing my own novel—Woodrell had already done what I was trying to do, with great success. How many Ozark crime novels could find an audience? Was there room for one more?

Luckily, there was an appetite for rural noir, and it has continued to grow and thrive in pop culture. Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone was made into a highly-acclaimed film. Gillian Flynn’s wildly bestselling novels, set in and around Missouri, have all been adapted for the screen. Ozark, True Detective, and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri have all plumbed the depths of this territory. A new documentary series on Sundance TV, No One Saw a Thing, digs into one of the most notorious crimes in Missouri; it was created by an Israeli filmmaker who was inspired by the shocking tale of violence and vigilantism in a small, Midwestern town.

Part of the appeal of rural noir is that, to people living elsewhere, the way of life might seem a bit exotic and unexplored. The isolation and the forbidding landscape lend a sense danger and tension. Anything could happen in a place that feels beyond the bounds of law, where people might cross lines to survive, where there are plenty of places to hide bodies so they’ll never be found.

While I’ve been thrilled to see my home represented on a larger stage, not everyone here is happy about the boom in rural noir. Some people complain that it’s making us look bad to the rest of the world, that we’re being portrayed as degenerate hillbillies. There’s merit in that argument. There’s a fine line between depicting the flavor of a region and crossing into mockery by reinforcing stereotypes, but for me it goes back to my poverty-stricken childhood in the Ozarks and the feeling that my own life, my own stories, were not valid or relevant, that they weren’t worthy of being visible to an audience. For a decade, Missouri was the meth capital of the United States. Poverty and drugs and a lack of opportunity are real problems here. Name any crime novel or TV show and I’ll tell you about a real crime that happened here that was more savage, more unbelievable, than anything that could be made up. Give me any backwoods stereotype and I’ll take you down a dirt road and show you something worse. There are good and bad people everywhere, and rural America is no different. Noir, by nature, shows the darker side.

When I meet people, they often comment that I, an ordinary Midwestern mom with two daughters, seem too pleasant to be writing gritty crime novels. If they could peek inside my head, they wouldn’t say that, but it’s a common misperception. As the popularity of rural noir grows, you can find plenty of lists of book recommendations in the genre, and nearly all of them contain the same handful of authors. There is no doubt that writers like Woodrell and Ron Rash, who are among my favorites, are must-reads in rural noir, but there’s an incredible wealth of authors and a wide variety of books to check out if you enjoy the genre. A few to try are Bonnie Jo Campbell’s American Salvage or Once Upon a River, Steph Post’s Lightwood, Mesha Maren’s Sugar Run, Amy Greene’s Bloodroot, Bryn Greenwood’s All the Ugly and Wonderful Things, Attica Locke’s Bluebird, Bluebird, Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects, Leah Thomas’s Wild and Crooked, and Amy Engel’s The Roanoke Girls.

I never imagined, as a kid, that dark, small-town tales would one day be so prevalent in pop culture, or that my own stories would be among them; that in some enviable suburb, a kid would sprawl out on plush carpeting, open a book or turn on the television, and see someone like me.

***