Dr Mortimer looked strangely at us for an instant, and his voice sank almost to a whisper as he answered: “Mr Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!”

Even now, this line from The Hound of the Baskervilles has the power to make my nape hairs prickle.

I first encountered the novel when I was ten years old. We were on a two-week family holiday in Brittany, renting a remote clifftop house overlooking the Atlantic. It was the mid-1970s, so there wasn’t much entertainment available beyond books and boardgames. There was a TV, but back then, before the advent of global satellite broadcasting, all the channels were in French. So each evening, after supper, my father would read aloud a chapter of the book.

Picture the small Breton house in its lofty, windswept location. Picture a family of five huddled in the sitting room. Picture a small boy listening rapt as Dr Mortimer tells Holmes and Watson about the awful demise of Sir Charles Baskerville.

By then, I had already read plenty of the Sherlock Holmes short stories. This was my first exposure to a full-length Holmes narrative, however, and I lapped it up. I couldn’t wait until nightfall came and we could hear the next installment of the adventure.

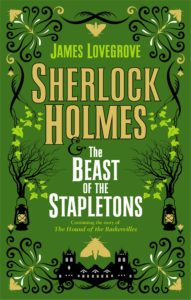

The Hound has stayed with me ever since. Of course, we all know that it was not some ghostly hell-beast, the manifestation of an ages-old curse. We all know that it was just a large, savage bloodhound/mastiff hybrid coated in a “cunning preparation” of phosphorus and unleashed on various Baskervilles by the naturalist Jack Stapleton, a ruthless relative who aspired to inherit the family title and fortune and was willing to murder anyone who came between him and his goal.

Yet the Hound remains a vividly chilling, genuinely spooky figure. Such is the skill with which Conan Doyle conjures up the menace of it, and evokes the bleak, treacherous Dartmoor landscape it inhabits, that a little part of us will always be convinced that Holmes and Watson were actually in the presence of something otherworldly after all. Our heroes may have been able to shoot the dog dead, but it lingers on in our imaginations, like any good literary monster. When we think of it, we forever see it galloping out of the mist, its chops slavering, its eyes all aglow, pounding towards us, eager to kill.

Although based on a creature from Devon folklore—the Yeth Hound, a spectral black dog that roams the moors and is believed to be a portent of death—Conan Doyle’s Hound has become more famous than its inspiration. Similarly, the novel in which it appears is certainly the best known tale in the Holmes canon, and probably the one that is most highly regarded by fans, critics and connoisseurs alike. Out of the four novels, The Hound of the Baskervilles has the cleverest plot and the purest structure. (Unlike the other three, it does not rely on a huge infodump of backstory at the end to explain what has gone before and fill out its page count.) It’s unusual in that the story requires Holmes to do surprisingly little sleuthing, and indeed he disappears from the action altogether for several chapters, leaving much of the heavy lifting to Watson. It is, above all else, a novel that revels in mystery and atmosphere, closer to Gothic fiction than crime fiction.

As Sherlock Holmes’s closest brush with the supernatural, The Hound of the Baskervilles demonstrates that the Great Detective’s powers are equal to any task, even combating forces that are seemingly beyond our ken.Yet, as Sherlock Holmes’s closest brush with the supernatural, The Hound of the Baskervilles demonstrates that the Great Detective’s powers are equal to any task, even combating forces that are seemingly beyond our ken. The Hound itself is no common blackmailer or thief or assassin. It is a thing of nightmares, so frightening that the sight of it alone can induce a fatal heart attack in one victim and send another hurtling to his death off a rocky outcrop while fleeing it. It is designed to scare not just characters in the novel but readers too, and when Holmes and Watson at last overcome it, and the artifice behind it stands revealed, our fears are not entirely allayed. This is no Scooby-Doo unmasking moment, when we can laugh as we understand that there was nothing to be afraid of, that the horror was all in our minds. We can’t help but remember that the Hound was trained, and tricked out in phosphorescent paint, and kept half-starved by its owner, for no reason other than to terrify and pursue and kill. It is an embodiment of evil. It is Stapleton’s jealousy, resentment and cruelty made flesh, a canine avatar of avarice.

That, I believe, is why the Hound has endured all this time, and why the novel, more than a century on from its first publication in serialised form in The Strand Magazine, has secured a lasting place in popular culture. Nobody can forget the book’s title character, once they have met it, even if the details of the story surrounding it may grow a little hazy in the memory afterwards. Like Count Dracula in the Bram Stoker original, the Hound looms perpetually over the events of the narrative even when it is, so to speak, offstage.

Professor Moriarty may be Sherlock Holmes’s nemesis, an archvillain every bit his equal in intelligence and perceptiveness, but the Hound is arguably the more formidable opponent, not least because—brutish, instinctual, carnal, inhuman—it represents everything Holmes is not. His ultimate victory over it is a victory over fear, proving that intellect should be the master of irrationality, that ego should always trump id.

Somewhere in all of us there is a Dartmoor haunted by a gigantic hound. We have seen its footprints. We know it lurks amid the swirling mist. We can only hope that we have an inner Holmes with the brains and fortitude to expose this demon for the monstrous fraud that it is.

***