In the morning, I’m shocked to see the envelope with the BLC Consulting logo. I hadn’t expected anything for a week, and it’s not even been three days. I open it in such a hurry that I tear off part of the letter.

Holy fuck.

I sprint up to the apartment and then back down again, and very soon it’s midday and I’ve been pacing back and forth outside Nicole’s resource center for an hour, jittery as a cat, until finally she comes out. She sees me from a distance and can tell from my body language that it’s good news. She smiles as she comes toward me, I hold out the letter, she scans it and right away says, “My love,” and her voice catches. I am overwhelmed by the certainty that a miracle has just taken place in our life. Both of us have tears in our eyes. I know I must resist the temptation, but I already have a strong urge to call the girls. Mathilde in particular, I don’t know why. Probably because she’s the more normal of the two, the one who’ll process it quicker.

Against all expectations, I have passed the tests. I’ve made it through.

Individual interview: Thursday, May 7.

This is unbelievable . . . I made it through!

Nicole hugs me tight, but she doesn’t want us to make a scene outside her workplace. I kiss a few of her colleagues and shake some hands in greeting as they head out for lunch. Everyone knows I’m looking for work, so when I go there I try hard to look my best, to appear as if I’m bearing up and not letting things get on top of me. For an unemployed person, being there when people are leaving the office is always tough. It’s not jealousy. The unemployment itself isn’t the hard part: what’s difficult is continuing to exist in a society based on labor economics. No matter where you turn, you are defined by what you don’t have.

But now everything’s different. I feel as though my chest has burst open, that for the first time in four years I can breathe. Nicole says nothing; she is jubilant, holding my arm and squeezing it as we make our way down the street.

Against all expectations, I have passed the tests. I’ve made it through.In the evening we go to Chez Paul to celebrate, even though we both know this is a real extravagance. We act as though it’s no big deal, but that doesn’t stop us from selecting our dishes via the price column on the menu.

“I’ll have a main course and a dessert,” Nicole says.

But when the waitress arrives I order two starters (œufs en gelée, which I know Nicole loves), and a half bottle of Saint-Joseph. Nicole swallows hard, then smiles with resignation.

“I’m so proud of you,” she says.

I don’t know why she says that, but it’s always good to hear. I hurry to get around to what I consider the most important point.

“I’ve thought about how I’m going to handle the interview. I figure they’ll have called in three or four of us. I have to stand out. My idea . . .”

And off I go. I’m like an excited teenager recounting his first triumph over a grown-up.

Every now and then Nicole places her hand on mine to let me know I’m speaking too loudly. I lower my voice, but within five minutes I’ve forgotten again. It makes her laugh. Good God, it’s been years since we were as happy as we are tonight. At the end of the meal, I realize that I virtually haven’t drawn breath. I try to tone it down, but I can’t control myself.

Rue de Lapp is buzzing as though it were summer. We walk arm in arm, in love.

“And you’ll be able to stop working at Logistics,” says Nicole.

It takes me by surprise, and Nicole raises a quizzical eyebrow. I put on a facial expression that would seem credible enough to me, looking rather ashen in the process. If I don’t get this job and end up in court with 25,000 euros to pay in damages . . . Thankfully Nicole doesn’t notice anything.

Instead of taking the métro at Bastille, I’m not sure why, she carries on walking, stops at a bench, and sits down. She rummages in her bag, takes out a little package, and hands it to me. I open it to find a little roll of fabric with an orange pattern, held together by a small piece of red string, at the end of which is a tiny bell.

“It’s a lucky charm. It’s Japanese. I bought it the day you were called in to take the test. So far it seems to be doing the trick.”

It seems silly, but it makes me very emotional. Not the gift itself. At least . . . I don’t really know anymore, but I feel emotional. I must have polished off the Saint-Joseph more or less on my own. It’s our life that I find moving. This woman, after everything we’ve been through, deserves every good fortune. As I stuff the talisman into my trouser pocket, I feel indestructible.

From now on, I’m in the homestretch.

No one’s going to stand in my way anymore.

Charles often used to say: “The only certainty is that nothing happens as planned.” That’s classic Charles. He loves nothing more than a momentous phrase or a lofty stance. I wonder whether he might be an orphan. Long story short, I had horrendous nightmares in the run-up to the interview, but in the end it went pretty well.

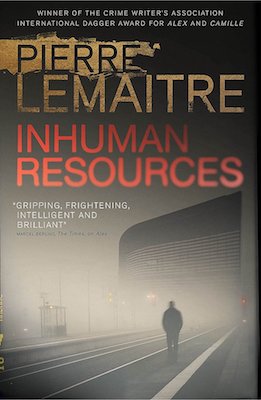

I had been invited to BLC Consulting’s headquarters in La Défense. I was biding my time in the waiting room, a large space with a luxurious carpet, uplighting, a stunning Asian receptionist, and discreet background music. A place tailor-made for boredom. I was a quarter of an hour early. Nicole had applied a very thin layer of foundation to my forehead to hide any trace of my bruise. I had a constant feeling that it was running, and I had to resist the temptation to check. In my pocket, I played the Japanese charm through my fingers.

Bertrand Lacoste came striding in and shook me by the hand. At fifty years of age, he came across as absurdly sure of himself, but quite affable.

“Would you like some coffee?”

“No, thank you, I’m fine,” I said. “Nervous?”

He asked this with a little smile. Slipping coins into the machine, he added:

“Yup, it’s always difficult finding work.”

“Difficult, but honorable,” I said.

He looked up at me, as if seeing me properly for the first time. “So no coffee?”

“Thank you, no.”

And we stayed there, in front of the machine, with him sipping his synthetic coffee. He turned his back and considered the reception area around him with an air of glum resignation.

“Fucking decorators—can’t trust them to do anything!”

Straightaway that set the tone for me. I don’t know exactly what happened after that. I was so pumped up it came out automatically.

“I see,” I said.

This made him start. “What do you see?”

“You’re going to play it all ‘casual.’”

“Sorry?”

“I said you’re going to play it all ‘relaxed,’ sort of ‘the circumstances are professional, but at the end of the day we’re all human beings.’ Am I right?”

He shot me a look. He seemed livid. I told myself I’d gotten off to a decent start, then continued:

“You’re playing on the fact that we’re more or less the same age to see whether I fall into the trap of being overfamiliar. And now I think you’re giving me this look to see if I panic and start backpedaling.”

I’m going to be open with you: you are the oldest of the four, but it’s not at all beyond the realms of possibility that your experience will make all the difference.’”His glare softened and he smiled:

“Right . . . well, we’ve succeeded in clearing the air, wouldn’t you say?”

I didn’t answer.

He chucked his plastic cup in the garbage can. “So, let’s get on with the serious stuff.”

He walked ahead of me down the corridor, still with that long stride. I felt like a confederate soldier a few minutes before the enemy charge.

He’d done his job well and studied my application carefully, incisively. The moment he came across a weakness in my CV, he pounced on it, exploiting the first sign of frailty in the candidate.

“He carried on testing me, but the tone was different now.”

“Did he tell you who he was recruiting for?” Nicole asks.

“No, not at all . . . There were just two or three clues. It’s all pretty vague, but maybe I’ll manage to find out more. It’s in my interest to get ahead of the game. You’ll see why. At the end of the interview, I said to him:

“‘I must say that I’m very surprised that you should be interested in a candidate of my age.’

“Lacoste pretended to be nonplussed, but eventually he placed his elbows on the table and stared at me.

“‘Monsieur Delambre,’ he said to me, ‘we are just another company in a competitive market. Everyone needs to stand out from the crowd. You with your employers, me with my clients. You are my wild card.’”

“But . . . what does that even mean?” Nicole asks.

“‘My client is expecting young graduates, which is what I’m going to give them; they’re not expecting an applicant like you—I’m going to surprise them. And then, between you and me, when push comes to shove in the next round, I figure the decision will make itself.’”

“Is there another round?” Nicole asks. “I thought—”

“‘There are four of you on the short list. The final decision will be based on one further test. I’m going to be open with you: you are the oldest of the four, but it’s not at all beyond the realms of possibility that your experience will make all the difference.’”

Nicole begins to look suspicious. She cocks her head to one side.

“And what is this ‘further test’?”

“‘Our client intends to assess a selection of their top execs. Your mission is to conduct this assessment. You will be tested, if you will, on your ability to test others.’”

“But . . .” Nicole still doesn’t see where this is going. “How does that work?”

“‘We are going to simulate a hostage taking . . .’” “What?!”

Nicole looks as if she’s about to choke.

“‘. . . and your task involves placing the candidates under sufficient duress for us to test various criteria: their coolness under pressure, their conduct in an extremely stressful scenario, and their loyalty to the values of the company to which they belong.’”

Nicole is struck dumb.

“But that’s outrageous!” she cries. “You have to make these people think they’ve been taken hostage? At work? Is that what you’re telling me?”

You have to make these people think they’ve been taken hostage? At work? Is that what you’re telling me?”“‘There will be a commando unit played by actors, weapons loaded with blanks, cameras to film their reactions, and you will lead the interrogations and direct the commandos. You will need to use your imagination.’”

Nicole is on her feet, disgusted. “That’s sick,” she says.

There’s Nicole in a nutshell. You’d think that her capacity for indignation would have lost its edge over time, but not a bit of it. When she feels scandalized, she can’t help herself—nothing will stop her. In these situations, you have to try to calm her down right away, to step in before her reaction gets out of control.

“You shouldn’t look at it like that, Nicole.”

“How should I look at it? An armed commando unit comes bursting into their office, threatens them, interrogates them, for how long? An hour? Two hours? They think they might die, that these people will kill them? All that just so their boss can have a bit of a laugh?”

Her voice is trembling. I haven’t seen her like this for years. I try to be patient. Her attitude is understandable. But I’m already fast-forwarding ten days, and it hits me: everything hinges on one single, palpable fact: I have to pass this test.

I try to smooth things over.

“I know it’s not very . . . But you have to look at the situation from a different angle, Nicole.”

“Why? Because you think this approach is acceptable? Why don’t we just shoot them too, while we’re at it?”

“Wait—”

“Or better still! Put some mattresses on the pavement without telling them, then hang them out the window! Just to see their reaction! Alain, have you gone completely mad?”

“Nicole, don’t—”

“And you’re really prepared to go along with this?”

“I understand where you’re coming from, but you have to see things from my side, too.”

“No way, Alain. I can understand anything, but that doesn’t mean I can forgive it!”

She has moved into our train wreck of a kitchen.

I see the two bits of drywall that have been holding up the sink for years. The current linoleum is even less resistant than last year’s, already curling up at the corners in pitiful fashion. Nicole, livid as she stands in the center of this mess, is wearing a woolen cardigan that she can’t afford to replace. It makes her look diminished. It makes her look poor. And she doesn’t even realize it. I take it as a personal insult.

“For Christ’s sake, all I know is that I’m still in the running!” I’m shouting now. The violence of my tone roots her to the spot.

“Alain . . . ,” she says, panic in her voice.

“Don’t ‘Alain’ me! Fucking hell, can’t you see we’re turning into tramps? We’ve been slowly running aground for four years . . . soon enough we’ll be in the ground! So yes, it’s disgusting, but so is our life—our life is disgusting! Yes, those people are sick, but I’m going to do it, you hear me? I’m going to do what they ask. Everything they ask! Even if I have to fucking shoot them to get the job, I’ll do it because I’m fed up . . . I’m sixty years old, and I’m fed up of having my ass kicked!”

I am beside myself.

I grab the wall unit beside me and yank it so violently that it comes away completely. Plates, mugs—everything comes tumbling down with a terrible crash.

Nicole cries out and then starts sobbing into her hands. But I don’t have the strength to console her. I can’t. Deep down that’s the worst thing about it. We’ve been fighting together for four years just to keep our heads above water, and one fine day we realize it’s over. Without knowing it, each of us has folded. Because even with the best couples, each one has a different way of seeing reality. That’s what I’m trying to say to her. But I’m so furious that I get it wrong.

“You’re able to have scruples and morals because you have a job. For me, it’s the opposite.”

It’s not the best way of putting things, but in the circumstances I can’t do any better. I think Nicole has gotten the general gist, but I don’t have time to make sure. I pull the door shut as I leave.

At the bottom of our building, I realize I’ve forgotten to put on a coat.

It’s raining and cold, so I turn up my shirt collar. Like a tramp.

__________________________________