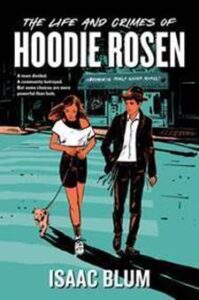

On December 10 2019, two shooters opened fire at a kosher supermarket in Jersey City, New Jersey, in a targeted antisemitic attack. Six people, including the assailants, were killed. The shooting at the market followed months of growing tension between a long-established community, and a new influx of Orthodox Jews. Within a week of the shooting, I started outlining my debut young adult novel, The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen, about Orthodox Jewish teen who finds himself caught in the middle of antisemitic violence. But I didn’t set my story in Jersey City.

Because that attack could have happened anywhere. According to the Anti-Defamation League, antisemitic incidents have been on a sharp rise in the United States, reaching an unprecedented peak in 2021–they have almost tripled since 2015. There has been deadly antisemitic violence all over the country: in Monsey, New York, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and San Diego, California. At a Texas synagogue, an armed man took four hostages during a Shabbat service. Both implicit and explicit antisemitic rhetoric has led to horrific bias incidents and hate crimes against Jews.

In my novel, Hoodie Rosen’s Orthodox Jewish community is moving to a new, mostly non-Jewish town called Tregaron. The Tregaron locals do not want the newcomers in “their” town, concerned that the sudden influx of Orthodox Jews will change the town irrevocably, for the worse. Led by their vitriolic mayor, they attempt to keep the Jewish community out, by stonewalling a construction project that would build a high-rise to house Jewish families.

Tregaron is not a real town. But it could be Jersey City. Brooklyn Orthodox Jews, priced out by high housing costs, started relocating to Jersey City, which led to tension between established residents and the Orthodox community. Tregaron could also be in the Hudson Valley, where Chester, NY officials attempted to block a housing development project that would bring a sizable Orthodox Jewish population to the town.

There are ways in which the entrenched communities are sympathetic. Residents of Chester pointed out legitimate problems that could arise from a jump in the town’s population. The new Orthodox community could stretch the public school budget, and a sudden increase in voters, especially if the newcomers vote as a single bloc, could disenfranchise other residents in local politics.

There are practical, legitimate demographic and socio-economic issues when one community, priced out of their old home, looks for someplace new to live. But it gets dangerous when that community is Jewish. We’re always one click away from an antisemitic meme or conspiracy theory, as the world has been, and continues to be, full of antisemitic sentiment. According to the ADL, Jews are the most targeted religious community in the United States when it comes to hate-motivated violence.

The perpetrators of the attack at the Jersey City kosher market were not Jersey City residents. They were not concerned about public school funding or shifts in local politics. They were radicalized anti-semites, who trained for the attack. They purchased and practiced using high-powered weapons in Ohio, before returning to the east coast to perform the attack itself. One of the attackers wrote social media posts suggesting that Jews are satanic, and are secretly in control of many powerful institutions, such as the police—satanism and secret domination are both common tropes in antisemitic extremism.

I can see how the two stories—the Orthodox community moving to a new place, and the radicalized extremists looking for a target—might appear unrelated. But they’re not. They feed into and off of each other. The Jewish community appears scarier because of the extremist rhetoric, and the extremists use the natural tension between communities to add fuel to their hateful fire.

All this plays out in my novel. An Orthodox Jewish community moves to a new town. The locals worry about how this new community will remake their long-time home. Those real concerns, fueled by insidious antisemitism from within and without, morph into hate that leads to deadly violence. I try to tell the story with as much humor as possible, and to end the novel on a hopeful note, but I also did my best to tell it as it actually happens. Because it was important to me to show that this kind of thing can happen anywhere in this country, at any time, leaving people dead and communities wrecked.

It was also important to me that it was a young adult novel. I’ve spent most of my adult life working as a middle and high school teacher. And I’m consistently impressed by my students’ earnest interest in different cultures and backgrounds. It isn’t just that they’re tolerant, though they are tolerant. It’s that they actively want to know about people who are different from them, who come from different places, who see the world through different lenses. I wanted to center teenage characters who work to understand each other, and in so doing, help to heal each other as well as their communities. Though their relationship has its ups and downs, Hoodie and the mayor’s daughter, Anna-Marie, build a strong friendship. They work to understand each other, and they help each other overcome both personal and community-based trauma.

I wanted to contrast the teens with their obstinate parents, adults who are, at best, set in their ways, at worst, bigoted and intolerant. Anna-Marie’s mother leads the charge to keep the Orthodox community out of Tregaron. Hoodie’s father is almost singularly focused on his construction project, trying to build a high-rise that will house more Orthodox families. When Hoodie and Anna-Marie erase antisemitic graffiti from headstones at the local cemetery, Hoodie’s father is furious, because he feels that the graffiti could be used as political leverage to help get the construction project off the ground.

I wanted the novel to reflect my earnest belief in kids. I believe that they can be better than the adults around them, and that they’ll be interested in reading a novel about a community most of them know almost nothing about. I also believe that this is the type of literature that helps tolerant young adults become proactive, activist adults, who will fight against the unnecessary hate and bias the rest of us have failed to eradicate.

***