How many times have you walked into a bookstore with a particular title in mind, and walked out with three others you hadn’t planned to buy? As readers, we’re drawn to a snappy title, a cool cover, a shout line that intrigues and excites. We decide, on a whim, to revisit an old favorite, or to try a new author, recommended by the bookseller’s handwritten review card. It happens to me all the time and, despite being a die-hard crime fiction fan, the books that end up in my bag come from a variety of genres.

I find myself continually frustrated by publishing’s obsession with genre; an obsession which is largely fueled by online browsing, where consumers rely on digital tags to lead them to a novel they’re likely to enjoy. But genre shouldn’t contain our preferences, only signpost them: the equivalent of a supermarket aisle marked as ‘breakfast cereals’ or ‘fruit & vegetables’. Sure, you might fill your cart more heavily from one aisle than another (hello, wine aisle) but you still shop the rest of the store.

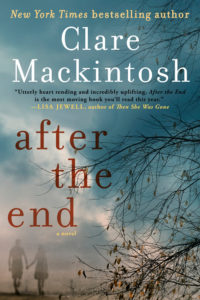

As a former police officer, it was perhaps inevitable I would turn to crime when I started writing fiction. My first three novels were psychological thrillers, and I would have written another, were it not for a story that tapped me on the shoulder and demanded to be told. A couple torn apart by a difference of opinion; a medical drama with a ‘sliding doors’ narrative and a moral dilemma at its heart. And not a single crime.

‘Write it,’ my editor said.

But I’d been conditioned to believe that readers demanded consistency; that a switch of genre would cause them to hurl a novel across the room in disgust. To test this theory, my publishers carried out a series of focus groups and market research activities, asking die-hard crime fiction fans what they loved about the genre—and about my own books specifically. The answers were illuminating. Not a single mention of ‘murder’, ‘deaths’, or ‘crime’; instead, what readers wanted were ‘twists’, ‘compelling characters’, ‘authentic writing’ and ‘tension.’

Doesn’t Jojo Moyes’ Me Before You have compelling characters? Isn’t Nicholas Sparks’ The Return packed with tension? And don’t tell me you guessed the twist in Rosie Walsh’s Ghosted…

The point I’m making is that it isn’t genre that matters, but story. I did write that book—After the End—and not a single reviewer complained about my genre-sidestep. Far from losing readers, expanding my writing has brought me additional ones.

‘People always want to ask a genre question,’ Kate Atkinson said, when she was interviewed following the publication of One Good Turn, part of her Jackson Brodie series. ‘It’s just the book I’m writing.’ Atkinson’s novels are variously found under ‘Thrillers & Suspense’, ‘Literary Fiction’ and ‘Private Investigator Mysteries’, and she’s far from the only author to flit between genres. Minette Walters was famous for crime before switching to historical fiction; John Connolly moves seamlessly between detective novels, horror and science-fiction; Nora Roberts crossed from romance to futuristic police procedurals. Even Agatha Christie—the doyenne of crime fiction—flirted with romance, under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott.

‘If I can do a detective novel,’ Colson Whitehead said, in a 2013 interview with Guernica, ‘and if I can do a horror novel, then why do it again? To keep the work challenging, I have to keep moving.’ Authors write for their readers, of course, but I have never met a writer who didn’t first and foremost write for themselves. We want to push boundaries, to test ourselves.

When I wrote After the End—a book variously shelved under ‘family suspense’, ‘medical drama’ and ‘contemporary fiction’—I learned a great deal about the writing process. A good novel should never be formulaic, but crime fiction comes with a built-in structure that can be missing in other genres. If your characters aren’t solving a crime, what are they doing? If they’re not running from a killer, what is propelling them forwards? The answer tends to lie in the protagonists themselves, rather than the plot, making my research less about forensics and prison sentences, and more about character values and backgrounds. Who were Pip and Max—the parents in After the End—and where did they come from? Did their cultural backgrounds impact on the way they dealt with a crisis? By getting to know my protagonists as well as I knew my own family, I could allow the story to develop organically from the choices I knew they would make.

The presence of crime alone isn’t enough to define a genre. Victor Hugo’s classic tale Les Misérables centers around a thief, but you won’t find the novel nestled next to Mo Hayder’s books, any more than you’ll find Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird by Stieg Larsson’s. One of my favorite novels of recent times is Where the Crawdads Sing; a novel I would never categorize as crime, despite the presence of a murder trial.

If you are a reader who only reads crime novels, I (tentatively, and ducking behind a wall for protection) suggest that you are missing out. Reading outside our comfort zone is a great way to get out of a reading rut, or to expand our horizons, and switching genres can be exciting and rewarding. Start by looking to see if any of your favorite crime novelists have written other types of books. If you love Stephen King’s writing style for crime, why not try his horror or fantasy novels? If you can’t bear to abandon crime altogether, add a few cross-genre novels to your reading pile, like Stuart Turton’s The 7 ½ Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle (crime mystery/science-fiction), The Crow Road, by Iain Banks (family saga/mystery), My Sister, the Serial Killer, by Oyinkan Braithwaite (crime/satire) or Sarah Pinborough’s Behind Her Eyes (psychological thriller/supernatural).

Right now, I’m working on Hostage, a thriller set on an airplane. It’s unarguably a crime novel, but my ‘writer’s toolbox’ has grown as a result of writing outside the genre. After the End taught me to put character first, to raise the emotional stakes, and to challenge the reader with moral dilemma. Whether we approach a book as a writer or as a reader, we shouldn’t be led by genre, but by story.

Step outside your crime reading comfort zone, and you might find a love of horror, or paranormal romance. How’s that for a plot twist?