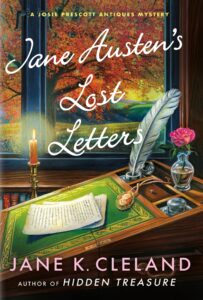

I come by my affection for Jane Austen honestly. My mother, Ruth Chessman, an author in her own right, was a devoted fan who wanted to share her greatest pleasures with the unborn me. She played classical music, ate a lot of fried chicken, vanilla ice cream, and tomatoes. (I know, I know. No surprise, these are three of my favorite foods.) My mother also believed that writing was the highest possible calling, so she read Pride and Prejudice, her favorite Jane Austen novel, aloud to me in the womb.

She wanted me to hear the words, the magnificent prose; to enjoy the wit; to appreciate the insights; to value exemplary work. Speaking of wit, in writing Jane Austen’s Lost Letters, I learned that Jane Austen’s incisive humor extended beyond her novel writing—some of her letters are laugh-out-loud funny. And just consider the title of one of her early works, a book she wrote in 1791, “The History of England from the reign of Henry the 4th to the death of Charles the 1st, By a partial, prejudiced, & ignorant Historian.” Isn’t that hysterical?

Lest you think I’m exaggerating my mother’s devotion to Jane Austen, I will tell you that I was named for her.

*

When I decided to write about Jane Austen’s letters, I embarked on a journey of research.

I researched Jane Austen’s publishing history, her business model, events that occurred during the relevant time (by relevant, I mean 1812 to 1814, which is the era I deal with in the letters in my book, Jane Austen’s Lost Letters), her stationery choices, how to mix gall ink, her pens, her attitudes toward her nieces and nephews, and so on.

Jane Austen’s letters represent a treasure trove of insights into her creative genius and allow us to know her in a more intimate manner than is possible through her novels alone. Consider this excerpt from the preface of the 1892 edition of The Letters of Jane Austen, edited by Sarah Chauncey Woolsey.

“Miss Austen’s life coincided with two of the momentous epochs of history—the American struggle for independence, and the French Revolution; but there is scarcely an allusion to either in her letters. She was interested in the fleet and its victories because two of her brothers were in the navy and had promotion and prize-money to look forward to. In this connection she mentions Trafalgar and the Egyptian expedition, and generously remarks that she would read Southey’s ‘Life of Nelson’ if there was anything in it about her brother Frank! She [remarks] that the making of the gooseberry jam and a good recipe for orange wine interests her more than all the marchings and countermarchings, the man[oe]uvres and diplomacies, going on the world over. In the midst of the universal vortex of fear and hope, triumph and defeat, while the fate of Britain and British liberty hung trembling in the balance, she sits writing her letters, trimming her caps, and discussing small beer with her sister in a lively and unruffled fashion wonderful to contemplate.”

Which is to say that Jane Austen’s letters provide a window into her personality and views of the world. Oh, how I wish more of her letters had survived!

*

Ms. Austen was, by any measure, an inveterate letter writer. Scholars agree that of the more than 3,000 letters Jane Austen probably wrote over the course of her life, only about 160 are extant. That we know of. The reason there are only about 160 letters is because her sister Cassandra burned the rest when she, Cassandra, was 70, decades after Jane’s death. No one knows why. According to her niece, Cassandra thought Jane was too “open and confidential.” But if that’s the case, why didn’t she destroy them all? Regardless, just as no one knows for sure how many letters escaped that fiery fate, no one knows how many are extant. Just because the world thinks 160 letters survived, what if there are one or two or even a dozen more? This is not idle speculation: On February 17, 2019 the news broke that six lines that had been cut from one of Jane Austen’s letters had been found. Six lines discovered after 200 years. Hello! It doesn’t get much more exciting than that! Except the lines didn’t refer to anything titillating or unseemly, worthy of being exorcised—they referred to laundry! By the way, the day after the discovery, the headline in The Daily Telegraph read, “Lost letter airs Jane Austen’s dirty linen in public.” How funny is that?

As Sarah Chauncey Woolsey observed, most of Ms. Austen’s letters focused on the minutia of daily life. Some addressed business matters related to her publishing career, and others dealt with more significant issues, but most reflected the joy she felt in her daily life. Let me give you some examples. I’ll start with an excerpt from a delightful letter to her beloved sister Cassandra.

Sloane St., Thursday (April 18, 1811).

My dear Cassandra,—I have so many little matters to tell you of, that I cannot wait any longer before I begin to put them down.

The badness of the weather disconcerted an excellent plan of mine—that of calling on Miss Beckford again; but from the middle of the day it rained incessantly. Mary and I, after disposing of her father and mother, went to the Liverpool Museum and the British Gallery, and I had some amusement at each, though my preference for men and women always inclines me to attend more to the company than the sight.

I love that! Robert B. Parker, in one of his Spencer novels, wrote that Spencer prefers spending time with that which man makes, rather than that which nature makes. People, not things. Me, too. I like a nature walk as much as the next girl, but mostly, I want to spend time conversing with people. Don’t you?

I also love Jane’s writing advice to her much-adored niece, Anna. Anna sent a partial manuscript of a novel to Jane. After complimenting a number of the characters, Austen advices avoiding clichés. She wrote, “I have only taken the liberty of expunging one phrase … ‘Bless my heart!’ It is too familiar and inelegant.”

Wonderful! And then there’s Jane’s marital advice to her niece, Fanny.

The scholar Janet Todd wrote, “Fanny saw Jane as a close friend, seeking her advice on love and marriage…. Despite Jane’s singlehood, Fanny obviously recognised her aunt’s wisdom and intellect.”

“Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without affection; and if his deficiencies of manner, etc., etc., strike you more than all his good qualities, if you continue to think strongly of them, give him up at once.”

Quite a trail-blazing attitude during a time of arranged marriages.

Jane Austen was her own woman, a woman of her times, certainly, but she followed her own light, and it is for that originality that we readers are most indebted. Thank you, Jane Austen. And thanks, mom, for making the introduction!

***