Writing a novel is a series of decisions—millions of them, from big ones like whodunnit and where to begin all the way down to a character’s eye colour and footwear. One of the most important choices a writer can make is the main character’s profession, which has implications far beyond the practical concern of whether you know enough about a specific job to write about it. The profession of your main character might affect the entire tone and character of the book you write: in fiction, perspective is everything.

At the beginning of the Golden Age of crime fiction, the amateur detective was a key figure, from Agatha Christie’s little old lady Miss Marple to Dorothy L. Sayers’ aristocratic hero, Lord Peter Wimsey. Christie made a point of choosing main characters who were likely to be underestimated: Poirot with his ridiculous moustache was an eccentric little Belgian immigrant, and Miss Marple was a gentle spinster from a tiny village, yet both of them outpaced the slow-thinking police officers who were officially in charge. Sayers’ Wimsey has the luxury of great wealth and social standing so he was able to elbow his way into places no civilian could go these days. It’s simply not credible to suggest that any of these great detectives could launch themselves into a twenty-first century crime scene and expect to be welcomed – so it’s a question of thinking about professions that provide characters with the skills and expertise to justify their position at the heart of the story.

For many years, the obvious choice has been to put a police officer at the centre of your plot. You are writing about the hunt for a killer—why not focus on the hunter? Well, because if you choose to write about a police officer, suddenly you are writing a police procedural, whether you intended to or not. More than any other genre, contemporary crime reflects the world around us as we write. In recent times the role and conduct of police officers has become ever more politically charged and ethically complex. As a writer I appreciate the challenge this presents, and I will always love it as a genre, but there’s no doubt it changes the dynamic of a novel considerably.

There is something familiar about a police procedural too—the structure and content can feel predictable, and a little bit safe. To come up with a new twist on the very stories we are telling can require changing our angle on the investigation. Some of the most memorable crime fiction characters of recent years are not police officers but pathologists or medical examiners like Patricia Cornwell’s Scarpetta, CSI technicians, forensic psychologists, forensic anthropologists, lawyers—jobs that involve people in some aspect of a crime and give them a unique role to perform. I have learned so much from reading about the ‘other’ jobs that people do in police investigations, especially when their jobs are integral to the resolution of the plot. What could be better than a new world to explore?

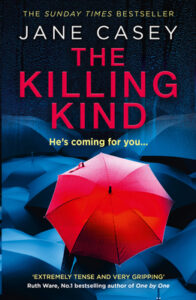

When I came to write my new book, The Killing Kind, I decided that I wanted to focus the narrative on someone whose job was crime-adjacent rather than a police officer. I already write a series of police procedural novels featuring London-Irish Met Police detective Maeve Kerrigan, and I wanted to shake things up for myself. I wanted a main character whose job brought them into contact with crimes and criminals in a way that was new to me, and hopefully to readers.

What I settled on was a job that fascinates me: a particular kind of lawyer called a barrister. As a job it specifically requires something that most of us find terrifying—public speaking. In the UK, Ireland and many other countries around the world, barristers are the lawyers who present cases in court. As a profession they tend to be charismatic, argumentative, a little egotistical and very bright. If they were doctors, they would be surgeons. If they were actors, they’d want to be centre stage.

Barristers can work on both sides, prosecution or defence, and most of them do both without hesitating. In other jurisdictions, a character’s choice to work for the prosecution or the defence may give an insight into their personal beliefs, but barristers are required to leave their own feelings out of their work, much as a doctor must treat any patient who needs their help. They follow a guideline known as the cab-rank rule, where if a case comes to you, you must take it, no matter whether you like the defendant or agree with the principles at stake. Justice must be done, and it is done when the prosecution case, whatever it may be, is tested to its limits. As a prosecutor, you do everything you can to state the facts of the case clearly and convincingly. In defence, you do everything you can to challenge the facts and the arguments being floated by your learned colleague on the other side.

It’s an ancient system, as reflected in some of the little eccentricities of the job – British barristers wear a horsehair wig and a black gown in court; they won’t shake hands with one another as it is traditionally regarded as an insult since it is one way to check whether your opponent is about to threaten you with a sword (yes, really!). They change in ‘robing rooms’ at court; they work out of sets of chambers where groups of barristers have their working day organised by the clerks who manage their diaries. Their working day can range from the glamour of the High Court to the grimiest of holding cells under a busy court. If they are successful, they may become Queen’s Counsel and write QC after their names. They are intimately familiar with the worst things that people can do to one another, and with the people accused of those crimes, and their professional life generally consists of things most of us would rather not think about. It’s both glamorous and gritty. That, to me, has endless dramatic potential.

The Killing Kind is not a legal thriller in the usual sense: it’s a thriller with a legal setting. Ingrid Lewis, my main character, is a very good young barrister, but through her job she has encountered a number of disturbing people—not all of whom wish her well. One former client, John Webster, has stalked her for years, tearing away at the fabric of her life. When someone threatens Ingrid, she assumes it’s Webster, but if it isn’t, she might need the help he offers her. The story forces her to choose between right and wrong, between keeping to the rules and breaking them, between accepted wisdom and a leap of faith. The plot wouldn’t work without her specific job but the law is not the means by which it is resolved. Cold law may provide the mechanics of the plot but pure emotion is what powers The Killing Kind: envy and frustration, love and hate.

The best crime novels are the ones that challenge, that question, that reflect our contemporary reality in a way that makes readers see it in a new light. It may be that the traditional police procedural isn’t the best means to do that anymore—and certainly it isn’t the only way.

***