Is January 2nd the saddest day of the year? It’s the day after the day after. It’s cold and snowy (but then, I live in Canada, and it’s cold and snowy around eight months a year). It’s a day of breaking resolutions and swearing that it—the bite of cake, the puff of smoke, the gnawed fingernail—didn’t count. Usually, as I look over the month’s thrillers, I know which ones will make the cut but this January is unusually rich, and there are excellent books this February and March too. I focused on the many impressive and inventive new voices in the mix, with a book by a favorite because there are not enough Lisa Lutz readers in the world.

Jessamine Chan, The School for Good Mothers

(Simon & Schuster)

Any of you ever argued about how many literary books are actually thrillers? I think of it as the Celeste Ng argument (or the Dostoyevsky argument, or the Gatsby argument) but the overlap between literary and thriller is quite large once you start thinking of all the classics which have crime as a device or an engine. In the case of Chan’s devastating debut, I thought about the Handmaid’s Tale. I thought about 1984, and I thought about the more recent Red Clocks by Leni Zumas. But I also thought of great nonfiction books about surveillance and poverty, like Matthew Desmond’s Eviction or Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family. But back to Chan’s book with its simple premise: A mother is having a very bad day, made worse by the interference of social workers and their mandate to investigate child abuse and neglect. Chan’s execution of her all too relatable story is a novel so good it feels like life, and so terrifying I wished for less verisimilitude.

Lisa Lutz, The Accomplice

(Ballantine Books)

Lisa Lutz has done quite a few things. She did funny with the Spellman files (which are very, very funny). She did a woman on the run with The Passenger. She did the hostile-to-toxic masculine culture of a tony private school in the Swallows. And she pulls off an inexplicable reading experience in the weird and, well, inexplicable Heads You Win. Given this stellar track record I had high hopes for The Accomplice, and Lutz delivers a humdinger. There are notes of past books in the story of Own Mann and Luna Gray, best friends and co-leaders of their pack in college. Everyone wonders why they are so close and not a couple; then everyone wonders while people around them keep turning up dead.

Nita Prose, The Maid

(Ballantine Books)

The Maid had me from its creepy Prologue, where a maid reminds the reader how much of your life she is privy to, to its sly ending in which the same maid slides out of view. Prose’s book uses the protagonist’s profession to great effect. Set in a small hotel—small enough so that the maid is a character and not a faceless provider of pillows and little bottles of shampoo—The Maid manages to make eccentricity charming. The resolution of the mystery is a lesson in seeing the hidden people who know much more about us than we do them. Take a maid.

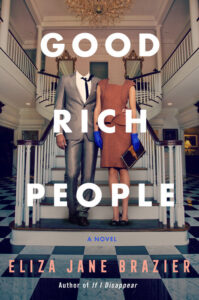

Eliza Jane Brazier, Good Rich People

(Berkley)

Brazier’s debut, If I Should Disappear, was a relative success. It was one of the many podcast-focused books I passed on reading. You see, I hate podcasts, and even typing the word is making me fidgety and bored, and there were a slew of podcast premises I was more than happy to skip. Yet when Good Rich People arrived, there was a fun premise: rich people bet against one another’s pet projects. Oh, not literal pets. They are playing the Most Dangerous Game: messing with people who already have messy lives. One invites a commoner to live in the guesthouse on their property Kato Kaelin-style. Then the others try to destroy the usurper. It makes for an unsubtle but fun skewering of good rich people, something my fellow Real Housewives watchers will appreciate.

Janice Hallett, The Appeal

(Atria)

As a book critic, I am not thrilled to thumb through something with over-the-top gimmicks or other cute ideas. The Appeal, a book deftly balancing the old and new, leans hard into its piecemeal structure comprised of e-mails, very local news stories, attorney correspondence, texts, police reports, and the ephemera of a community theater troupe, the Fairway Players (see above for the level of difficulty in making eccentricity charming). To say that I didn’t hate it is already giving Hallett the win, but I will venture further and say she takes her structure and crushes it. Thus Hallett has written a not twee mystery set in the amateur theatrical society of a quaint English village. Well done.