Louis Armstrong did not need to be told that the honky-tonks that were connected were the honky-tonks where you wanted to be. He learned this from King Oliver, whom he worshipped. Oliver was twenty years older than Armstrong. In many ways, the veteran cornetist and bandleader was both a mentor and father figure to the young musician. “I never stop loving Joe Oliver,” said Armstrong. “He was always ready to come to my rescue when I needed someone to tell me about life and its little intricate things and help me out of difficult situations.”

Oliver had a big, bald head that he often topped with a bowler hat. He could be formal and stern, but he had a laying style on the horn that was raw and spontaneous. His genius was arranging his playing in such a way that it melded in interesting ways with others in the band. As a composer and arranger, Oliver created musical configurations that gave new meaning to jazz. His band, which he co-led with trombonist Kid Ory, was at the vanguard of the new music.

Armstrong would come to watch King Oliver play nearly every night at Pete Lala’s, one of the most renowned jazz venues in Storyville. Clarence Williams, a pianist born in Plaquemine, Louisiana, who was part of the deluge of musicians who had arrived in New Orleans around the turn of the century, remembered Lala’s as the center of the universe:

Round about 4 a.m., the girls would get through work and meet their P.I.’s—that’s what we called pimps—at the wine rooms. Pete Lala’s was the headquarters, the place where all the bands would come when they got off work, and where the girls would come to meet their main man. It was a place where they would come to drink and play and have breakfast and then go home to bed.

Armstrong also remembered Lala’s:

These pimps and hustlers, et cetera, would spend most of their time at [Lala’s] until their girls would finish turning tricks in their cribs . . . They would meet them and check up on the night’s take . . . Lots of prostitutes lived in different sections of the city and would come down to Storyville just like they had a job . . . There were different shifts for them . . . Sometimes two prostitutes would share the rent in the same crib together . . . One would work in the day and the other would beat out that night shift . . . And business was so good in those days with the fleet sailors and the crews from those big ships that come in the Mississippi River from all over the world—kept them very, very busy.

Everyone knew that Pete Lala’s was a mob-connected club. The owner was Peter Ciaccio, a Sicilian immigrant, which was confusing because there were two other clubs in the district owned by men named Lala, including Big 25, another popular club with a business license issued to John T. Lala. All of these localities were part of a group of clubs owned and operated by Italians. Rightly or wrongly, clubs in the district owned by Italians were believed to be mafia-connected. King Oliver didn’t even need to tell Little Louis that these clubs were the place to be. The connected clubs were, ostensibly, the most reliable when it came to their dealings with the musicians.

Armstrong knew this partly from experience. One of the first places he held a steady gig was at Matranga’s, which was located in Black Storyville.

Matranga’s was nothing like Pete Lala’s, which was cavernous and well appointed. Matranga’s was a barrelhouse saloon that had been in existence since at least the late 1880s. Its clientele was primarily Black though the ownership was Sicilian—a common arrangement in New Orleans at the time. Being a Matranga, the owner of the club, Henry Matranga, was “a man of respect.” Remembered Armstrong, “Henry Matranga was sharp as a tack and a playboy in his own right. He treated everybody fine, and the colored people who patronized his tonk loved him very much.”

Armstrong knew that Matranga’s was a mafia club. Using King Oliver’s example as his guide, he not only tolerated the fact that the club was connected, he preferred it. In his memoir, he gave an example of why. One night at Matranga’s, a fight broke out that was quelled by the club’s bouncer, who went by the name of Slippers. It was Slippers, as Armstrong remembered it, who got him the gig at Matranga’s in the first place. Slippers may have been a hulking thug, but he loved jazz.

[He] liked my way of playing so much that he himself suggested to Henry Matranga that I replace the cornet player who had just left. He was a pretty good man, and Matranga was a little in doubt about my ability to hold the job down. When I opened up, Slippers was in my corner cheering me on. “Listen to that kid,” he said to Matranga. “Just listen to that little son-of- a- bitch play that quail!” That is what Slippers called my cornet . . . Sometimes when we would really start going to town while Slippers was out in the gambling room in the back, he would run out on the dance floor saying: “Just listen to that little son-of-a-bitch blow that quail.” Then he would look at me. “Boy, if you keep on like that, you’re gonna be the best quail blower in the world. Mark my words.”

The night a fight broke out, Slippers was in fine form. To Armstrong, it was further example of why a jazz musician was better off in a mob-controlled club.

That night, a ditchdigger from one of the levee work camps came into the place and gambled away all of his earnings in the back gambling room. Slippers had his eye on the guy from the moment he entered. The guy became angry upon losing, as gamblers sometimes do; he vented his frustration in the bar area by threatening to rob everyone in the place. Slippers tried to reason with the fellow: “Shut your mouth, friend, or you’ll be out of here on your back side.” The guy quieted down, but after a few minutes he was at it again, claiming that the house was running a crooked game. So Slippers grabbed the guy by the scruff of his neck and led him aggressively toward the door.

The guy had a gun, a large .45, which he pulled out and fired wildly in the direction of Slippers.

Through all of this, Louis Armstrong and his band were playing some down-home barrelhouse blues—until the shots rang out. Color drained from the face of Boogus, the piano layer, while Garbee, the drummer, started to stammer, “Wha, wha, wha . . . what was that?”

“Nothing,” said Louis, trying to act nonchalant, though he also was terrified.

Slippers pulled out his pistol and fired back; he winged the ditchdigger in the leg. The guy went down. Slippers walked over and relieved the man of his gun, then continued what he started by tossing the man out onto the sidewalk. A horse-drawn ambulance arrived and the troublemaker was carted off to the hospital. Said Armstrong, “Around four o’clock the gals started piling in from their night’s work. They bought us drinks, and we started those good old blues.” In some honky-tonks, a shooting was a startling event that would lead, at least, to the club closing for the night. Not at Matranga’s.

To Armstrong, it was a mutually beneficial alliance: “One thing I always admired about those bad men when I was a youngster in New Orleans is that they all liked good music.”

Being aficionados of jazz was one thing, but even more significant was the role men like Henry Matranga could play in making it possible for Armstrong to function in an unjust world. One night when Armstrong wasn’t even scheduled to perform at Matranga’s, he stopped in for a beer.

The tonk was not running, but the saloon was open and some of the old-timers were standing around the bar running their mouths. I just said hello to Matranga when Captain Jackson, the meanest guy on the police force, walked in. “Everybody line up,” he said. “We are looking for some stick-up guys who just held up a man on Rampart Street.” We tried to explain that we were innocent, but he told his men to lock us up and take us to the Parish Prison only a block away. There I was trapped, and I had to send a message to Maryann: “Going to jail. Try and find somebody to get me out.”

Louis spent the night in jail, and then, miraculously and without explanation, he was released.

While I was in the prison yard I did not realize that Matranga had contacted his lawyer to have us all let out on parole. I did not even have to appear in court. It was part of a system that always worked in those days. Whenever a crowd of fellows were rounded up in a raid on a gambling house or saloon, the proprietor knew how to “spring” them, that is, get them out of jail.

Armstrong now had a protector in New Orleans; that protector was the mafia.

___________________________________

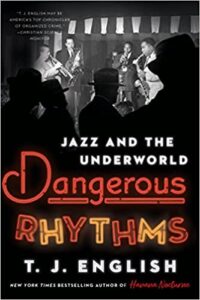

Excerpted from Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld, by T.J. English. Published by William Morrow & Company. Copyright, 2022, T.J. English. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.