The writers’ arsenal may come similarly equipped for most authors, but Jenny Milchman has a secret weapon that can’t be equalized: Joy.

It’s the thing that sustained her through eleven years and seven unpublished manuscripts before Cover of Snow debuted in 2013. That book won the coveted Mary Higgins Clark Award. It also introduced readers to what would become the hallmarks of Milchman’s fictional landscape: character driven suspense featuring (perhaps unknowingly) strong female protagonists who are made to confront the internal and external threats that afflict them, all set against the backdrop of a fictional town in the Adirondack mountains named Wedeskyull.

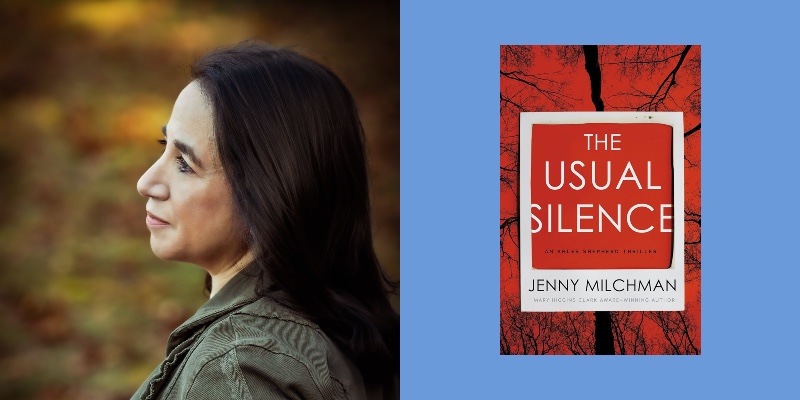

It may come as no surprise, then, that Milchman’s sixth novel, The Usual Silence (Thomas & Mercer: October 1, 2024)—the first in a series, connected by community and character—takes those elements and spins them into familiar yet fertile new territory. Psychologist Arles Shepherd, traumatized by the secrets of her own shadowy past, has devoted her professional life to helping troubled children (even as her personal life is in a state of crisis)—a mission she intends to continue with the opening her own treatment center in the wilds of upstate New York.

It’s here that Arles manufactures the opportunity to treat twelve-year-old Geary Monroe, whose harried (and unsuspecting) mother, Louise, has dominated her thoughts for a quarter century, ever since Arles encountered her picture as a child. Little does she know that their reunion will come to intertwine with a current missing persons case in which a young girl’s desperate father has enlisted the help of two true crime podcasters to do what the police cannot: find his daughter and bring her home.

Drawing on the author’s own background—Jenny Milchman holds a degree in clinical psychology and spent a decade in practice—The Usual Silence introduces a dynamic heroine who may yet find her own joy if she can first learn to make peace with the lingering remnants of her haunted history.

John B. Valeri: The Usual Silence is your first true series book (whereas your earlier books shared a common place but with singular protagonists). What was the conceptualization process like for developing a character and circumstances that would carry over – and how did that impact your approach to writing the story itself?

Jenny Milchman: I had no idea, I mean really no clue, how much I would love writing a series. You’re right, my first five novels share the same setting, the fictional Adirondack town of Wedeskyull, and The Usual Silence takes place there too. Arles Shepherd is a local who’s grown up in Wedeskyull and after graduate school—she’s a psychologist—comes back to live.

The way Arles came into existence is one of those stories writers dream of, and if we’re very lucky, get to have every once in a while. My new publisher at Thomas and Mercer reached out to my agent and invited me to breakfast. Naturally, I was so excited I could barely eat, though the publisher graciously plied me with pastries. She also asked if I’d ever thought about writing a series, especially one that might take into account my first career as a psychotherapist, which the publisher said readers are fascinated by, but don’t get to see as frequently in fiction as, say, police and legal procedurals (a subgenre I love—Tana French! Robert Dugoni!) With that suggestion, the idea of a psychological procedural, and Arles Shepherd, were both born.

As I wrote The Usual Silence, I felt Arles’s world unfolding in ways that will take many books—should I be so lucky—to flesh out. For instance, at thirty-seven years of age, she’s never had a love interest before, but she meets someone she holds at arm’s length in this first book. She also has a vicious stepfather who needs dealing with, but that doesn’t happen until the second novel, due out next September.

JBV: Arles Shepherd epitomizes the notion of the “complex character,” complete with a mysterious past and self-sabotaging tendencies. How did you endeavor to balance her darker qualities with more relatable or sympathetic ones? Also, what degree of her backstory did you need to know before committing her character to paper?

JM: You’re the second person to talk about Arles’s less “likeable” character traits, and given how depthful your literary analysis always is, I now know this to be a thing! But it’s funny because in writing Arles, I didn’t see those dark qualities in the same way. She does have a mysterious past, which severely damaged her, giving rise to self-sabotage and dissociation and things that threaten to derail her life. In many ways, her life already is derailed—at thirty-seven years of age, she meets her very first love interest in this book.

The Usual Silence is about trauma and the long shadow it casts. The less lovely traits and behaviors and thought processes trauma gives rise to. A trauma survivor never fully gets out of that shadow. But if the trauma is faced and dealt with, which is what Arles helps other people do, and tries to varying degrees of success to do for herself, there can also be days spent in the sun.

And trauma survivors are tough! They know how to fight, for themselves and sometimes others. I admire Arles so much because she will literally kill if someone needs her to.

In terms of how much I knew before I began writing—almost nothing. Arles sat down in that chair in her office in chapter one, and then revealed what she’d been through.

JBV: Arles is a psychologist who treats troubled children with traumatized pasts. You hold a degree in clinical psychology and spent a decade in practice at a community health center and your mother holds a PhD in the subject. Please talk about your approach to drawing on your own knowledge and the expert insights of others to achieve an authentic and sensitive portrayal of the work (and the resultant ethical and moral dilemmas that sometimes result).

JM: So, here’s how that happened. The whole family business thing.

When I was in my second year of college, my parents asked me if I had any thoughts about my major and future career possibilities and life after graduation. How I was going to earn a living, you might say.

This was a fine thing to ask because I had a plan, a great plan. I was going to major in literature and become a poet and live in the woods in a cabin. I might’ve planned to build the cabin myself—is that how Thoreau did it?—I’m not sure.

Because I had never wielded a hammer, and also because I loved people and had taken abnormal psych and loved it, my mother ventured to ask whether I wanted to consider a double major, lit and psychology?

But the siren’s call of writing never ceased. And while doing my internship at the community mental health clinic you reference, I was assigned this very scary case.

Content warning here for violence against an animal.

A mother brought in her tiny, five-year-old daughter to see me because the child had just killed a bird. It was the family pet.

And as I raced to figure out what had made the girl commit this act, how to make sure she didn’t do anything like that or worse again—violent acts often escalate—it was almost as if life were a suspense novel. I sat down and wrote my very first (never to be published) psychological thriller.

So in many ways, my career as an author was born, Athena-like, from the Zeus’s head of psychology. Till then I had wanted to be a poet. I had no idea how compelling crime and suspense and even horror fiction could be—even though I read it!

In terms of ethical or moral dilemmas, there’s a reason that first novel never got published. Though I didn’t include any identifying details, it followed my real life as an intern much too closely. My first career now informs my writing, but everything else is made up, or talked over with experts, as you say—which include my mother!

JBV: One of the story’s young characters, Geary, is neurodivergent (Autistic). How did you tap into Geary’s inner-self and unique abilities to render a nuanced portrayal of his being (rather than allowing him to become a convenient plot device). Also, tell us about the importance of capturing the dichotomous feelings of hope and frustration that parents or loved ones feel in their desire to relate to, or understand, such a child as Geary.

JM: I’m really happy you read Geary that way because that was my intent and I love that kid.

That said, if a much earlier draft than the final one—and this novel went through full rewrites in the close to double digits—you would have encountered a different, lesser version of him.

I knew that I owed Autistic individuals a complex portrait, which put on the page how someone with a mind that works in unique and different ways lives and experiences the world. But Geary evolved over those nine drafts, and one big way he did so was when my publisher and I decided to enlist a culture reader. That person—whom I thank in my acknowledgements—helped me see the ways I had inadvertently fallen into patterns of projecting my own lens and not fully making room for Geary’s.

I also very intentionally chose not to make Geary a point of view character. Although I deeply hope Autistic people and their loved ones will find representation in this book—and the full range of love and also frustration you mention—I recognized the limits of my ability to enter a vastly different type of perceiving and experiencing.

We authors are always doing that, to some extent, and I love deep POV—another of the characters in The Usual Silence is a forty-something male Maine old timer! Which is not me clearly. But I personally feel there are limits. The reader sees how Geary’s mother—who is not neurodivergent—and his psychologist perceive and relate to him, but not how Geary perceives and internally engages, and for me that’s a crucial distinction.

JBV: Much of the book plays out against the backdrop of the remote Adirondack Mountains. Tell us about the importance of this setting – both in terms of its thematic resonance and the realistic distancing from modern technology and surveillance.

JM: A fictional town in the Adirondacks called Wedeskyull has been the setting of all five—soon to be six—of my published books. (And a lot of unpublished ones besides). Wedeskyull is my Castle Rock. My Yoknapatawpha County. It’s the movie camera that pulls back to an aerial view such that the viewer sees thousands of points of light, each one a lit-up home or a campfire; a person or a group of them. There’s a story to each and every one of those. And they all interact, layer upon layer, in the way of small towns.

I also love—and fear—nature. And within that awe is the potential for an awful lot of drama. Three of my prior books have been wilderness thrillers, and in some ways The Usual Silence is one too. The remote location compels the characters to confront forces—both within themselves and without—that couldn’t exist in another kind of setting.

The isolation that surrounds every one of us—even in a crowd—is a theme in this book and reflected by its sense of place.

In terms of the fact that this also means there’s often no Wi-Fi or cell signal—well, that definitely contributes an ominous overtone! But I am careful not to make crucial plot points rely on this lack, even though it is true to the region. Because of how remote the setting is, even if a call were able to be placed, help would not arrive quickly.

JBV: In the book’s acknowledgments, you note the exhilaration of working with a new agent and editor. In what ways did the collaborative process benefit the final manuscript – and how did you find this particular experience to be creatively (and maybe even spiritually) fulfilling in ways that others hadn’t?

JM: This book came to be because a publisher reached out to my new agent and asked if I would have breakfast with her. This is a thrilling event for an author. And an intimidating one! At that breakfast my soon-to-be publisher planted the seed for a series.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch—which is Thomas and Mercer—my soon-to-be editor was preparing to give me free rein (ranch, rein, get it?) with the book I was about to write. It was an exhilarating experience. I sat down and penned a tale, and then nine drafts later, amid some bleeding (hopefully only on my part), the book you read was ready.

Many more people, brilliant and attentive minds, entered into this creative process than I’d ever had with any of my prior works. It was hard, but deeply soul-satisfying. So I guess spiritual isn’t the wrong word. One of the most unexpected aspects loops back to what you asked initially—that this is a series and I was able to create not just the onion of Wedeskyull, with all its layers to be peeled, but the onion of my series character. There are so many places she can go to, and things she will have to do there, that I can only hope I get the chance to write them.

JBV: You have been refreshingly candid about the challenges of sustaining a career as an author given the publishing industry’s ever-changing landscape. In retrospect, what do you credit with the fortitude to stay the course despite setbacks and uncertainty – and what words of caution or guidance would you offer others who are considering pursuing this devotion?

JM: Devotion is a great word for it. Another is joy—and that’s what enabled me to get through eleven years and seven unpublished manuscripts before I broke through, and then some pretty hair-raising twists and turns after. The sheer joy of writing a new story, getting to know the characters and seeing how everything plays out, is what keeps me going. While I pay for this when editing and revising, which is nowhere near as much fun for me, little compares to the joy of sitting down and writing a new book.

It helps if there are people out there cheering us along. I always had a strong agent in my corner—validation from the industry—even when finding the love connection with an editor, or having a career that makes publishers come calling, was challenging. But I wouldn’t want emerging writers to feel that if they don’t have industry validation, that’s reason to stop. Find it in other sources—a critique group, a batch of trusty readers, your friend or partner or even your mother. A pet can offer the means to go on sometimes. Just turn outward for support, and whatever you do, don’t stop.

At the same time, understand that this is both an art and an industry. The business side is real. And if you want a long-lasting career as an author, then you don’t just want any agent, you want the right agent for you. One who really gets your work and where you hope to go with it.

And you don’t just want any editor and publisher, you want ones who envision you where you long to be—because they’re going to be the ones who get you there, both via making your book into one that’s good and smooth and polished enough to achieve your dream, and via allocating the budget and marketing to make that happen. They need to be committed to providing enough of a runway that you can take off. Which is a very tall order. You may only find it in fits and starts and stages—amid setbacks as you say, John. That’s how it went for me.

JBV: Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

JM: I just turned in the second in the Arles Shepherd series. In it, Arles does something that’s needed doing for over thirty years. I couldn’t believe that it happened.

And I wrote it.