One should regularly refresh one’s acquaintance with the classics, for it is always an instructive exercise. What we imagine we remember of them as often as not turns out to be a hotchpotch of fragments retained from sleepy mishearings at bedtime, from condensed and bowdlerised ‘versions for children’ devoured on rainy Saturday afternoons—amongst an older generation, Dell Comics have a lot to answer for—and, above all, from the cinema. Bram Stoker’s Dracula in particular suffers, some might say gains, by association with the many film adaptations that have been made of it, although ‘adaptation’ is not always the justified word. In most of our minds now, when we think of the evil Count, there springs up at once an image of the clay-white, ruby-eyed, needle-fanged visage of the ineffable Christopher Lee, his high narrow head set necklessly upon the flounced collar of his black opera-cape, a sucked and sere fruit du mal.

By a coincidence that would have pleased, or perhaps worried, Stoker himself, Lee’s Dracula in the cheaply made but immensely stylish Hammer movies bears a marked and eerie resemblance, as surviving photographs attest, to the great Victorian ham Sir Henry Irving, especially in the role of Mephistopheles in W. G. Wills’ version of Faust, which entered the repertory of Irving’s Lyceum Theatre in London a dozen years before the publication of Dracula in 1897. Irving was the Irish-born novelist’s mentor, mephitic life model and blood-sucking friend, and Stoker’s memoir, Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving, might profitably be read in tandem with his Transylvanian Traumbuch. From 1878, Stoker acted not only as managing director of the Lyceum, but was Irving’s acolyte, prop and general dogsbody until the great man was forced to surrender control of the theatre in 1898.

Irving’s Lyceum, where he tyrannised the staff, including Stoker, no doubt, and constantly upstaged his leading lady, Ellen Terry, inevitably reminds us of Castle Dracula as described by Jonathan Harker in the opening chapters of the novel, with the Count and the three frightful vampire sisters, who are at once sapphic, incestuous and irresistibly erotic, putting on a lavish performance and vying for the life-blood of the diligent and impenetrably innocent Harker. (Incidentally, who but a Victorian ex-civil servant turned hack novelist would have dared to set the scene for coming horrors through the witness of a solicitor’s clerk-cum-estate agent?)

The novel’s castle is a far cry—and there are many far cries in the air hereabouts—from the cardboard Gothic pile erected by Hammer’s set designers. Paradoxically, given Dracula’s predilection for night and darkness, the Hammer movies, shot in gorgeous, acrylic-bright colours that seem always about to brim over and bleed into each other, present a noble ancestral mansion suffused with light, whereas at the end of the book’s first chapter what Harker arrives at is ‘a vast ruined castle, from whose tall black windows came no ray of light, and whose broken battlements showed a jagged line against the moonlit sky’. Similarly, Stoker’s Count Dracula, ‘a tall old man, clean-shaven save for a long white moustache’, is a drab figure indeed compared with Christopher Lee’s icily immaculate aristocrat, a Byron of the Carpathians. Let there be light, said Hammer, and we looked upon it, and found it good.

It might be said of Stoker’s Dracula that it was a movie waiting to be made. Aside from the incarnadined Count’s many guest appearances on screen, some fourteen adaptations of the novel have been filmed so far, and it is from these, rather than from the primary source, that the image of Dracula has been painted on the world’s wall, from Bela Lugosi’s 1931 static monolith to Christopher Lee’s and Frank Langella’s muscular, handsome and sinuously seductive matinee idols. In the happy formulation of the Dracula scholar Nina Auerbach, Stoker’s children of the night—‘Listen to them—the children of the night. What music they make!’ —are turned by the magic of movies into ‘children of the light’.

Yet it is an artificial light. What strikes us in the novel is how much of the action takes place under the broad radiance of the English day. Stoker’s Dracula, though he cleaves to the night, is perfectly free to stroll about the daytime streets of London exercising his eye for the girls. When Jonathan Harker, back home and recovered from the nervous collapse brought about by his narrow escape from Castle Dracula, spots his almost-nemesis in Piccadilly one day, the figure he glimpses, younger now than he was in Transylvania and sporting a black moustache and a pointed beard, is more flâneur than hell-hound, more Burlington Bertie than Satan’s spawn.

Although Stoker cannot hope to match the sumptuous sheen achieved by the Hammer technicians, his vampire is an infinitely more fascinating and complex invention than Christopher Lee’s relentlessly single-minded demon. The original Dracula, the ‘tall old man’ with the long white moustache, expands and develops. The life-blood that he sucks from others makes him grow physically younger while at the same time it helps his stunted mind to mature. In Stoker’s version of him, Count Dracula, originally a ‘soldier, statesman, and alchemist’, is partly based on a cosmeticised version of Vladislav III, ‘Vlad the Impaler’ (1431–76); our Dracula is a great lord with a pedigree stretching back to Thor and Wodin. His people, as he proudly insists, were the mighty warriors of Central Europe. ‘We Szekelys’, he tells Harker, ‘have a right to be proud, for in our veins flows the blood of many brave races who fought as the lion fights, for lordship.’ He lists off the many battles and wild victories his family took part in, some of which will be all too familiar to us today:

Who more gladly than we throughout the Four Nations received the ‘bloody sword’, or at its warlike call flocked quicker to the standard of the King? When was redeemed that great shame of my nation, the shame of Cassova, when the flags of the Wallach and the Magyar went down beneath the Crescent, who was it but one of my own race who as Voivode crossed the Danube and beat the Turk on his own ground?

Plus ça change . . .

In these passages of aristocratic grandiloquence one can almost hear Stoker smacking his lips in vicarious delight; the Victorian bourgeois did love a lord, even one as blood-soaked as Dracula. The novelist’s own origins were, if not exactly humble, certainly not lordly. He was born in 1847 in the highly respectable Dublin suburb of Clontarf—opposite his birthplace today is a Dracula museum, housed, somewhat bizarrely, in a fitness centre—to a father working in the Civil Service in Dublin Castle, the seat of British power in Ireland, and a mother who would regale her son with tales of her native Sligo and in particular the cholera epidemic that swept through the county when she was a girl, claiming thousands of lives and provoking scenes of mass hysteria and cruelty.

Young Abraham—interestingly, he gave his first name to the chief of his vampire hunters, Professor Van Helsing—was a sickly child, and seems to have spent the first seven years of his life bedridden, though what the disease was that afflicted him is not recorded (the late Victorians were peculiarly prone to contagions every bit as mysterious and debilitating as vampirism). He studied at Trinity College, where his successes included—surprisingly, given his early frailty—being named University Athlete. From the start he seems to have had ambitions to be a professional writer, but dutifully followed his father into the Civil Service; his first published book was the racily titled The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland. In his spare time he wrote stories, a number of which were published, and he also supplied drama criticism, unpaid, to the Dublin Evening Mail. In 1867, while he was still at Trinity, he had seen Henry Irving act in a production of Sheridan’s The Rivals and was immediately smitten by the actor’s mesmeric charm; thirteen years later, after Stoker had wangled his way into the Irving circle, the actor offered him the job of managing director at the Lyceum; thrilled, Stoker immediately resigned his drab day job and moved himself and his wife to London and the bright lights.

Dracula was his fifth novel. Nina Auerbach is of the opinion that the trial and conviction of Oscar Wilde in 1895 ‘probably shocked’ Stoker into writing it—Wilde was convicted on 25 May 1895, the same day that Henry Irving was knighted—for Wilde’s two-year imprisonment for acts of gross indecency ‘gave Victorian England a new monster of its own clinical making: the homosexual’, a creature who, ‘like the vampire . . . was tainted in his desires, not his deeds’. This may be somewhat tendentious—no book has ever sprung from a single source—but it is possible that Stoker had homosexual tendencies, and may even have been a fellow traveller with Wilde’s shadowy cavalcade of panders, pimps and rent boys. Certainly he knew Wilde, who had unsuccessfully proposed to Florence Balcombe, later to be Stoker’s wife.

Whether its inspiration was homo or hetero, Dracula is certainly a secret casebook of sexual anxiety and obsession. It is the quintessential fin de siècle pre-Freudian text, published at the end of an age of certainties and on the brink of a new and catastrophic century. All the terrors are here: the marauding outsider, the plague-ridden deviant, the predatory New Woman. The book can even be read as a cry of dismay before the prospect of a rampant mutation of capitalism that would sweep away the last of the post-feudal decencies and usher in a new barbaric order, with roots buried deep in primordial savagery. It is surely significant that when the book’s little band of vampire hunters seriously get down to business, one of their first initiatives is to form, as Mina Harker’s journal has it, ‘a sort of board or committee’. After the family, the committee or board is the primary nineteenth-century bourgeois unit, while Dracula is the bad aristocrat, the feudal lord who preys upon his vassals instead of doing his duty and protecting them. The old order changeth, and the new order must step in and take control.

An essential of the classic text is ambiguity, that protean quality which allows of a multitude of interpretations, none of which is definitive whatever claims are made for it. There have been, and will be, thousands upon thousands of scholarly readings of the ‘deep grammar’ of Dracula and its author’s intentions, conscious or otherwise. As we saw, Nina Auerbach considers the court conviction of Oscar Wilde to have been the spur that goaded Stoker to write the novel; another critic, Talia Schaffer, finds Wildean references peppering the text, as when Jonathan Harker, trapped in Castle Dracula, wonderingly writes: ‘When I found that I was a prisoner a sort of wild feeling came over me’—and certainly the public airing of what Wilde got up to while dining with ‘panthers’ marked the end of the Victorians’ studied innocence in matters sexual. However, Professor Auerbach also gives much weight to late nineteenth-century male terror of the so-called New Woman, whose rough ways Mina Harker sneers at, albeit somewhat nervously. The changes wrought in Mina and, far more markedly, in Lucy Westenra by Dracula’s sanguinary attentions are, Auerbach surmises, ‘symptomatic of the changes men feared in all their women’.

For commentators of a traditional psychological bent, Bram Stoker is, next to Sophocles, the greatest diagnostician of the Oedipus complex. Dracula is the mighty Father who must be destroyed in order that the Mother be released into the arms of her son, or sons. Stoker’s vampire hunters, his Famous Five, for all their Victorian strait-lacedness do bring to mind Freud’s terrifying image in Totem and Taboo of feral bands of brothers hunting down their Stone Age Father in order to release the desired Mother —in this case Mina—from his sexual clutches.

However, Phyllis A. Roth, in a stimulating and splendidly titled essay from 1977, ‘Suddenly Sexual Women in Dracula’, thinks the Oedipal interpretation does not go far enough. For Professor Roth, the real motivation of the men who destroy Lucy, ‘save’ Mina and annihilate the Count is a simultaneous terror of and lust for the ‘suddenly sexual woman’ who at the end of the nineteenth century strode forth into their hitherto safely sanitised world—sanitised on the surface, that is, for of course the two elephants in the Victorian drawing room were wide-scale prostitution and endemic syphilis. As we would expect, Roth makes much of the ‘sperm’ from Van Helsing’s candle—wax candles were made from whaleoil—that ‘dropped in white patches’ on Lucy’s coffin and ‘congealed as they touched the metal’, and of the many female mouths that open invitingly throughout the book, only to be revealed immediately as disguised versions of the vagina dentata. Roth is struck, rightly, by Harker’s fascination with the three female vampires of Castle Dracula and their ‘brilliant white teeth, that shone like pearls against the ruby of their voluptuous lips’, lips which he felt in his heart ‘a wicked, burning desire’ to be kissed by.

It is, however, the vengefulness of the vampire hunters that catches Roth’s strongest attention. Lucy Westenra, who at the start of the tale is little more than a flibbertigibbet and a flirt, is certainly and suddenly sexualised by Dracula, and must at all costs be destroyed. And who better to destroy her than her erstwhile fiancé Arthur Holmwood, later Lord Godalming—there is an entire thesis to be written on the class distinctions in Dracula—who is led down into her tomb and handed the hammer and the wooden stake, the point of which he places over her heart so that the narrator of this passage, the redoubtable Dr Seward, can ‘see its dint in the white flesh’, and then strikes the first of a series of killing blows:

The Thing in the coffin writhed; and a hideous, blood-curdling screech came from the opened red lips. The body shook and quivered and twisted in wild contortions; the sharp white teeth champed together till the lips were cut, and the mouth was smeared with a crimson foam. But Arthur never faltered. He looked like a figure of Thor as his untrembling arm rose and fell, driving deeper and deeper the mercy-bearing stake, whilst the blood from the pierced heart welled and spurted up around it.

It is an extraordinary moment, matched only—surpassed, really—by the infamous scene in Chapter XXI; one of the most horribly erotic passages in all non-pornographic fiction, and the inspiration surely for Pauline Réage’s Story of O and Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, in which Dracula is surprised in the act of forcing Mina Harker to sup from an opened vein in his breast:

With his left hand he held both Mrs Harker’s hands, keeping them away with her arms at full tension; his right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Her white nightdress was smeared with blood, and a thin stream trickled down the man’s bare breast which was shown by his torn-open dress. The attitude of the two had a terrible resemblance to a child forcing a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk to compel it to drink.

Article continues after advertisement

This scene, and the later ‘salvation’ of Mina, who with the destruction of Dracula survives at the price of sacrificing her ‘sudden’ sexualisation, identifies for Professor Roth the central drive of the novel, which is ‘primarily the desire to destroy the threatening mother, she who threatens by being desirable’.

Well, yes. But after these waylayings and elaborate muggings in the groves of academe one cannot but feel a little sorry for the Adamic Bram Stoker, pot-boiler and man of the theatre, who set out to write a rattling yarn that would freeze the cockles of our hearts and who in the process succeeded, no doubt to his own astonishment, in creating a deathless classic.

___________________________________

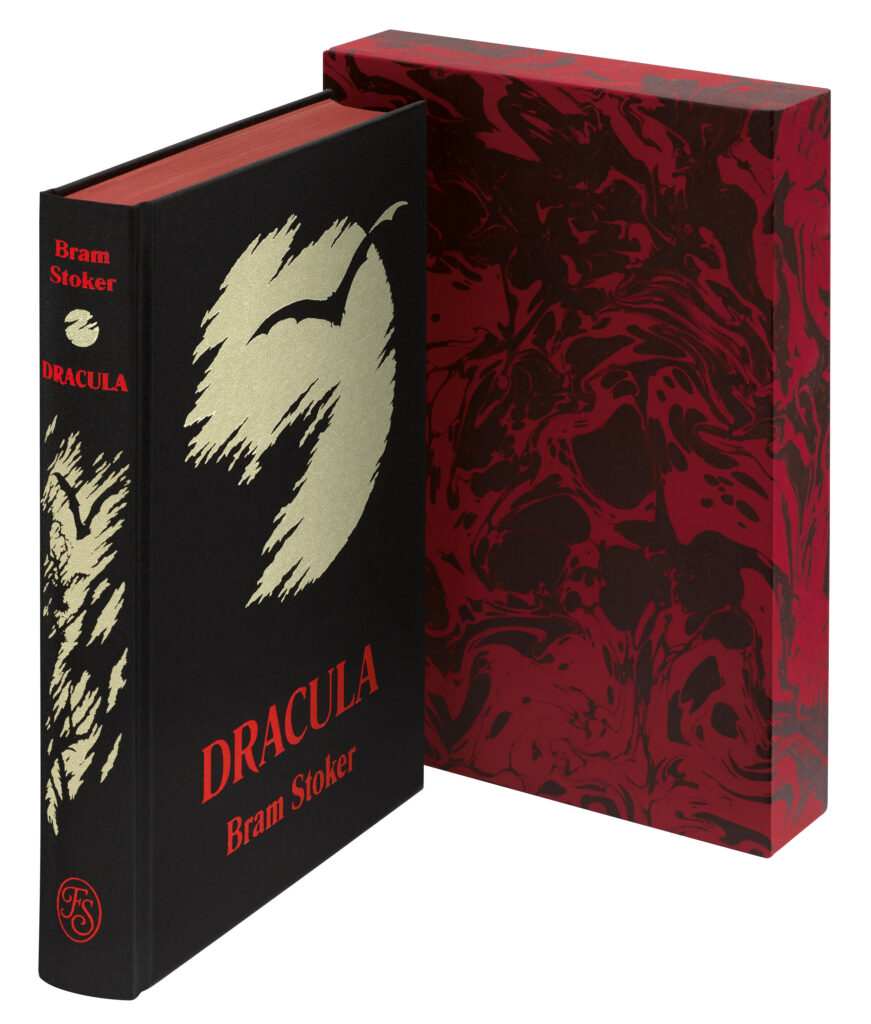

From John Banville’s introduction to The Folio Society edition of Bram Stoker’s Dracula is illustrated by Angela Barrett and exclusively available at foliosociety.com/dracula