On June 12, 1950, a British journalist and bureau chief for Reuters News Agency in West Berlin made Cold War-era history. John Peet, 34, stood in front of a crowd of more than 200 international reporters, summoned to East Germany’s government information office, formerly home to Hitler’s Propaganda Ministry. The place where Joseph Goebbels had once briefed the Nazi press was bursting at the seams. No one knew what the news would be, except for Peet.

In fact, Peet was the news.

“I simply cannot consent to take [part] any longer in the warmongering,” began the crow-like Peet in fluent German, with an upper-class British accent, “which threatens not only the Soviet Union and the People’s Democracies, but which is also well on the way to converting my motherland, Britain, into a powerless American colony.”

In his speech, Peet claimed that West German rearmament, though not officially admitted, was in full swing, and the country was producing poison gas and rifles. The accusations sent waves of silent shock through the room. A voice from the crowd shouted: “When did Mr. John Peet join the Communist Party?”

“John Peet was never a member of the Communist Party and is now non-party,” replied Peet, causing even greater confusion.

A huge media furor ensued. The New York Times, for one, reported that Peet’s action “stunned” colleagues in the U.K., U.S. and Germany alike. To some, his defection was an act of idealism and bravery. Others saw it as “professional suicide.”

Back in London, the Reuters office received a telex from him with the news, but Peet’s shocked editors tabled the dispatch while they tried to figure out how to handle it. The situation was embarrassing, to say the least. How did Reuters, one of the most trustworthy news suppliers in arguably the most important city during the Cold War, fail to recognize the enemy within its ranks?

But while Peet’s defection made front-page news worldwide, there is much more to it. In his ambitiously titled autobiography The Long Engagement: Memoirs of a Cold War Legend, Peet claims to have been recruited as a sleeper agent by the Russians in the late 1930s. He described a series of not-quite-missions that sound like a weird mix of George Clooney’s Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, with a hint of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

Peet was a man consumed by espionage. Not only had he amassed a deep library on the topic, but he also knew many people from intelligence circles—most notably British double agent Kim Philby, part of the infamous Cambridge University spy ring, and Harvey Matusow, a self-professed ex-Communist who, after souring on the party, turned FBI informant. Matusow testified during the McCarthy era against other alleged Communists, only to later recant those testimonies.

Could it be that Peet, given his interest in espionage and his intelligence-world connections, was in fact an agent for the Russians? According to his autobiography, he was. His daughter Miriam, though, says being a spy was “one of [her father’s] secret desires,” a kind of wishful thinking rather than reality. Neither Peet’s archival file at the Stasi (East Germany’s state security ministry) nor the one in Moscow says anything about him being a Soviet agent.

So is that aspect of his memoir a fiction? What is the truth?

John Peet in (front row, extreme right) in the early 1930s in the Bootham School, York. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

John Peet in (front row, extreme right) in the early 1930s in the Bootham School, York. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

Primrose has a message for daffodil

Once Peet decided to defect, the whole process was carefully orchestrated by the East German government. “It was made clear to me that I would play the cross-curtain move their way,” wrote Peet in his memoir.

Before leaving, Peet wiped his place of all possible evidence that would incriminate him or any of his friends. His first attempt to burn documents over the bathroom sink, conducted during the daylight with closed windows, nearly asphyxiated him. So he tried again after dark, when clouds of smoke from the windows wouldn’t be so obvious. Afterward, he disconnected and inspected the pipe under the sink to make sure nothing got stuck in the U-bend. Then he began waiting.

A few days later, Peet got a phone call that sounded like a gag straight out of an Austin Powers movie. His East Berlin connection said in an unnaturally high-pitched voice: “Primrose has a message for daffodil. 1600 hours on Monday. I repeat, 1600 hours on Monday.”

“Having convinced any possible tappers that something fishy was going on, he rang off,” remembered Peet.

It was time. On Sunday, June 11, 1950 Peet loaded all his earthly possessions into his Simca and drove through the Brandenburg Gate, which stood on the then-invisible border between East and West Berlin. By his account, his new life began at 3 p.m. precisely, when he drove down a quiet, tree-lined street in East Berlin and, as instructed, turned sharply into a garage entry: “As I drove in, the garage door opened, closing behind me as soon as I was inside.”

During the first months of his defection, East German authorities made sure Peet was completely isolated from any Western contacts. In the meantime, his actions blew back on his family and former employer. MI5, United Kingdom’s domestic counterintelligence and security agency, cut short Peet’s brother’s career as a documentary filmmaker for BBC. And it initiated a careful vetting process for all future job applicants at Reuters.

‘One of the unusual Englishmen of our time’

Who exactly was John Scott Peet and how did he get to this place?

Peet was a man of many faces, a character of extraordinary complexity and depth. Before defecting to East Berlin, he had gone through an odd succession of jobs. He had served in the British Guards Regiment, taught English in Prague, fought in the Spanish Civil War, worked as policeman in Palestine and been boss of Reuters’ Berlin bureau right after the war, reporting on the Nuremberg trials. Renowned spy novelist Len Deighton, a personal friend of Peet’s, called him ”one of the most intriguing men I have ever met,” and went on to conclude that his life was a “puzzle.” In its obituary, The Guardian called Peet “one of the unusual Englishmen of our time.”

Peet was born on June 29, 1915 in London, in a family of liberal, middle-class Quakers. Introduced to Communism early, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain as a teenager, but grew disappointed with its lack of revolutionary energy. Coming from a family of journalists, Peet started working as an advice columnist for a local London newspaper. In 1935, he joined the British Guards Regiment, but soon got bored by “the fierce and often senseless discipline.” He bought his own discharge after only a few weeks of service.

Yearning for adventure, Peet tried, unsuccessfully, to volunteer with the Ethiopian army to help fight Italian fascists. Having witnessed Hitler’s rise to power during a 1933 trip to Germany, he enlisted in the International Brigades, a multinational team of volunteers recruited and organized by Communist International to fight on the side of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War. In September 1937, he went to fight Francisco Franco’s fascists in that war—first as an interpreter, then as a machine gunner. In the summer of 1938, he took part in the Ebro offensive and was wounded in the right ankle.

It was in Spain a few months later where Peet, according to his memoirs, got recruited by NKVD, the Soviet secret services, while waiting to be repatriated back to England.

An invitation to ‘provide information’

John Peet as an English teacher in Prague in 1936 Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

John Peet as an English teacher in Prague in 1936 Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

“We were stationed in an out-of-the-way Catalan village, and one day a comrade stuck his head into the battalion office where I was working… I was needed urgently, he said, and it was all very hush-hush,” wrote Peet.

A “thickset, middle-aged man in a khaki uniform without insignia or badges of rank” was waiting for Peet in a sparsely furnished peasant cottage. Speaking fluent but heavily accented German, he interrogated him fairly thoroughly. Then he spoke about the importance of strategic political and military information for Spain’s left-wing political coalition, the Popular Front.

“He asked me if I had listened carefully and understood what he was talking about,” remembered Peet. “I replied, ‘If I understand you rightly, you are asking if I would be willing to be a Soviet spy.’ He looked shocked and assured me he meant nothing of the sort. But the broad popular front needed bright young assistants to provide information in the fields he had indicated, and would I be willing?”

Peet had already decided. Having taken up arms against fascism, he saw intelligence work for the Soviets—in his view, the only power that had effectively aided the Spanish Republic, and the only reliable anti-fascist force—as simply a different way to further the struggle.

The stranger told Peet that once back to Britain, he should cut any links with the Communists and become “a humdrum normal member of society, with a proper job, paid-up health insurance and a bit of money in post office savings.” He also told him he should wait to be contacted and under no circumstances should he reach out to the Soviets. Peet received code words by which his future handler would identify himself. Then he was repatriated to England on December 7, 1938.

‘’One day in August 1939, as war in Europe loomed, Peet’s phone rang. The caller, who refused to identify himself, asked for an urgent meeting at a nearby street corner. At first Peet hesitated. But then the man said: “This is against all the rules, but do you like Spanish watches?” Peet recognized the code words and agreed to the meeting.

The stranger appeared to be a “very normal middle-class Englishman” with “tweeds, a moustache and a pipe.” He gave Peet his first lessons on how to switch buses and subways to shake away any possible tails and how to use dead-letter drops to pass secrets to fellow agents. When finished with his instructions, the stranger fixed a place and time for their next meeting. Then he jumped on a passing bus and disappeared.

During subsequent meetings Peet’s handler strongly advised him to find a proper job for tactical reasons. So in August 1939, when he left for the Middle East to become an officer with the Palestinian Police, he was duly informed that “the firm” had no objections.

After his police stint, he began working as a journalist for the English-language section of Radio Jerusalem, where he stayed until 1945. Just after the war, Peet secured a sub-editor position at Reuters’ European news desk, working first in Vienna and then in Warsaw. In 1949, he became Berlin bureau chief for Reuters. One of Peet’s first assignments there was to interview Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp, in his death cell. Upon meeting, Peet offered Höss a cigarette, but the Nazi waved it away with German pedantry—smoking in cells was prohibited.

The anecdote comes from Victor Grossman, an 93-year-old American expatriate living in Berlin, who knew Peet for three decades. Grossman, a Harvard-educated leftist, had changed his identity and fled to the then-Soviet Zone in fear of reprisals for his radical politics. He met Peet while working as his assistant at the Democratic German Report, an eight-page, bi-weekly English-language propaganda publication.

Peet was appointed editor-in-chief of DGR in 1952. Using the pseudonyms Eustace Gordon and Frederick Ford, he wrote countless articles exposing the ex-Nazi officials active in West Germany’s postwar political and military circles. One of Peet’s key targets was Hans Globke, chief of staff and closest confidant to Germany’s postwar chancellor Konrad Adenauer. Globke became the main target of Communist propaganda, both because of his role in western anti-Communist policies and his previous role in drafting legislation under the Nazi regime. Peet managed to exploit British fears of West German rearmament and the dark Nazi past like no one else in East Germany, according to historian Stefan Berger, who with colleague Norman LaPorte, published an in-depth 2004 profile entitled “John Peet: An Englishman in the GDR.”

John Peet on holiday in England, c. 1937, just before going off to the Spanish Civil War. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

John Peet on holiday in England, c. 1937, just before going off to the Spanish Civil War. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

‘A fancy-dress kidnap’

Life seemed good for Peet in the early 1950s. In 1952 he married Georgia Taneva, a survivor from Ravensbrück, Hitler’s concentration camp for women. The couple had a son and a daughter. Georgia hailed from a prominent Communist family.

Democratic German Report circulation rose from 1,000 to 38,000, half of which was distributed in Britain’s socialist circles. Peet embraced his new propagandist role with fervor, but his past still dogged him. One day in early 1954, more than 14 years after Peet’s alleged recruitment, a Soviet citizen in East Berlin vaguely associated with the journalistic circles suddenly produced the recognition signal and arranged a meeting with a superior. Peet found the renewed contact “rather disturbing.” Four years after his infamous defection, he had become a well-known public figure in both East and West Germany. As editor-in-chief of DGR, he was the English voice of East Germany; the slightest suspicion of his being an agent for the Soviets, he wrote, would have been “embarrassing for all parties.”

“But despite these reservations I kept the appointment. The Cold War was at that time reaching new dimensions, West German rearmament was as good as settled, the USA was brandishing the atom bomb in which it still had great superiority; and with all its faults the Soviet Union appeared to be the only hope for mankind,” said Peet.

At the meeting, Peet recalled, he tried to explain that his position was somewhat delicate, but was tactfully reminded that the agreement he had entered into years earlier must be honored. What followed next was a series of what Peet described as “preposterous suggestions,” surpassing even his wildest espionage fantasies.

“First of all, he wanted to make the acquaintance of a particular western correspondent working in West Berlin. Nothing easier, I said—I meet this particular correspondent every week or two for lunch, and all he had to do was drop in by chance at the same restaurant,” said Peet. Instead, Peet’s Soviet contact proposed a staged car breakdown, where he would appear accidentally as a friend in need. This plot seemed too complicated, so Peet refused to participate.

Ideas got crazier. The following week, the Soviet contact suggested, as Peet called it, “a fancy-dress kidnap.” According to the plan, Peet would drive to Berlin’s British sector dressed as a British officer with two other “sergeants” to “arrest” a German man suspected of spying in East Germany. Peet rejected this mission too.

In the following weeks, the Soviet contact floated more ideas. None was as ridiculous as the kidnapping, but Peet rejected them all. Eventually, he agreed to pass along “a certain amount of West Berlin journalistic scuttlebutt” to them.

Then, the handler offered an intriguing proposal: Peet would attend the 1954 Geneva Conference on the Far East, intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War (1950-1953) and the First Indochina War (1946-1954). He agreed right away, seeing it as a good opportunity to escape his mundane East German grind and join “the international foreign correspondents’ circus,” meeting some old friends.

“In Geneva we all milled around at the press center bar, at press conferences and at lavish receptions where you were liable to find yourself chatting with Chou En-lai [a.k.a. Zhou Enlai, the first prime minister of the People’s Republic of China] at one moment and John Foster Dulles [U.S. secretary of state under Dwight D. Eisenhower] at the next,” remembered Peet.

But at their next meeting, the Soviet contact floated a new, “long-term plan,” in which Peet was supposed to seduce female employees of various Geneva-based United Nations agencies. Expense money would be provided for Peet to take out his love conquests to fancy restaurants and nightclubs. Needless to say, Peet was perplexed. Although he married four times in his lifetime, he wasn’t exactly the suave ladies’ man suitable for such an assignment.

“[The Soviet contact] hinted broadly for quite a while until I interrupted to tell him that the seduction of prospective spies was definitely not my line, and I had to hurry back to Berlin to get on with my normal public-relations job,” remembered Peet.

At their next meeting in Berlin, Peet said he didn’t see any future in their further collaboration. The Soviet contact tried to convince Peet to continue and said he would talk to his supervisors. A few days later Peet’s phone rang—no future meetings.

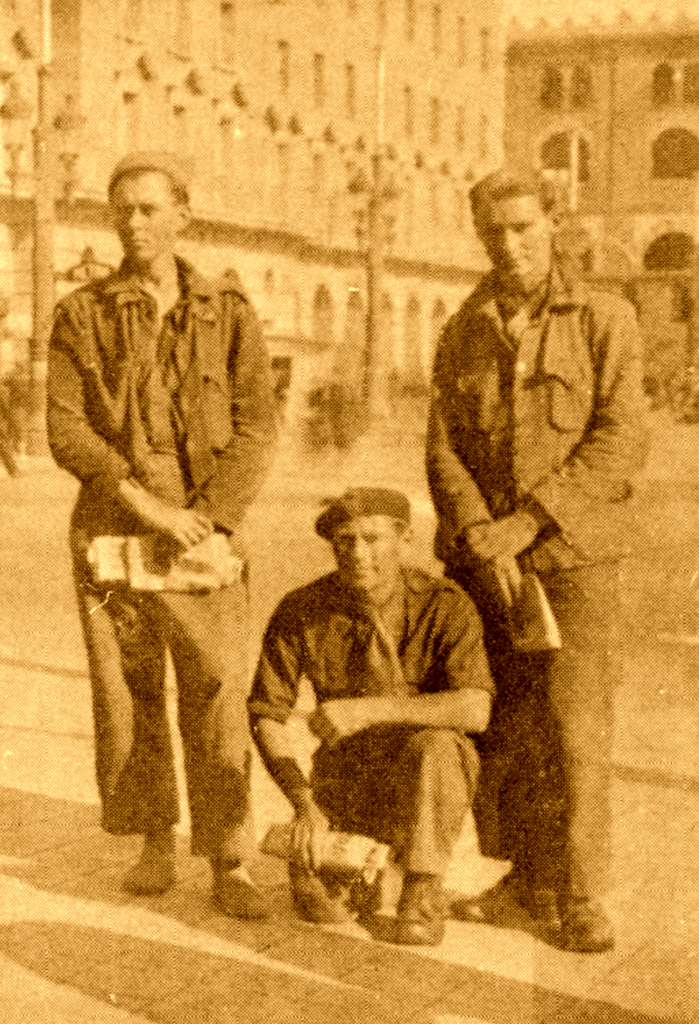

John Peet (left) in Barcelona in October 1938 for the disbanding of the International Brigades. The same year, according to him, he was recruited as a spy by the Soviet secret services.

John Peet (left) in Barcelona in October 1938 for the disbanding of the International Brigades. The same year, according to him, he was recruited as a spy by the Soviet secret services.

Going stale in the job

As the years passed, Peet became something of an institution. His East Berlin office, located mere meters from Checkpoint Charlie, the best-known Berlin Wall crossing point, became a meeting point for the western journalists chasing the latest Cold War story.

“Anyone wanting to know what was really happening in Berlin went to him,” says Len Deighton. “Freddie Forsyth, a splendid researcher and a mutual friend, would I’m sure be ready to acknowledge John’s help.”

Peet indeed was friends with Frederick Forsyth, who as revealed recently, was a spy in his own right, working for MI6 for more than 20 years. Well known for his anti-fascist sentiments, Peet supposedly inspired Forsyth’s 1972 novel The Odessa File, in which a journalist goes hunting for a former commandant of a WWII concentration camp.

In the early 1960s, Peet did some acting himself, playing an Englishman in at least three films made by the East German state-owned film studio. One of them, the espionage thriller For Eyes Only (1963), seems like a classic art-imitates-life case. “First, I found myself acting the head of MI5, and only last week I was a full-blown British general, coolly accepting the capitulation of the German forces in Denmark at the end of World War Two. The scene will probably land up on the cutting room floor, but it was nice while it lasted,” joked Peet.

According to Deighton, John Peet was “a newspaper man of the old school” and “a doubter.” Not surprisingly, his disbelief in the East German political system grew through the years. So did his discontent with the Democratic German Report.

“He thinks he is going stale in the job, but what other job can he do in East Berlin?” asked American journalist Earl Morris in a 1971 New York Times article titled “Expatriate Chess on the Other Side of the Wall.”

By the mid 1970s, the DGR outlived its usefulness, says Victor Grossman: “All the Nazis were either retired or dead [and] the German Democratic Republic got recognized.”

The publication folded in December 1975, after 23 years in print and a few days after John Peet’s 60th birthday. He spent his remaining years translating the correspondence of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels into English. He married a fourth time, to a much younger East German woman named Edelgard.

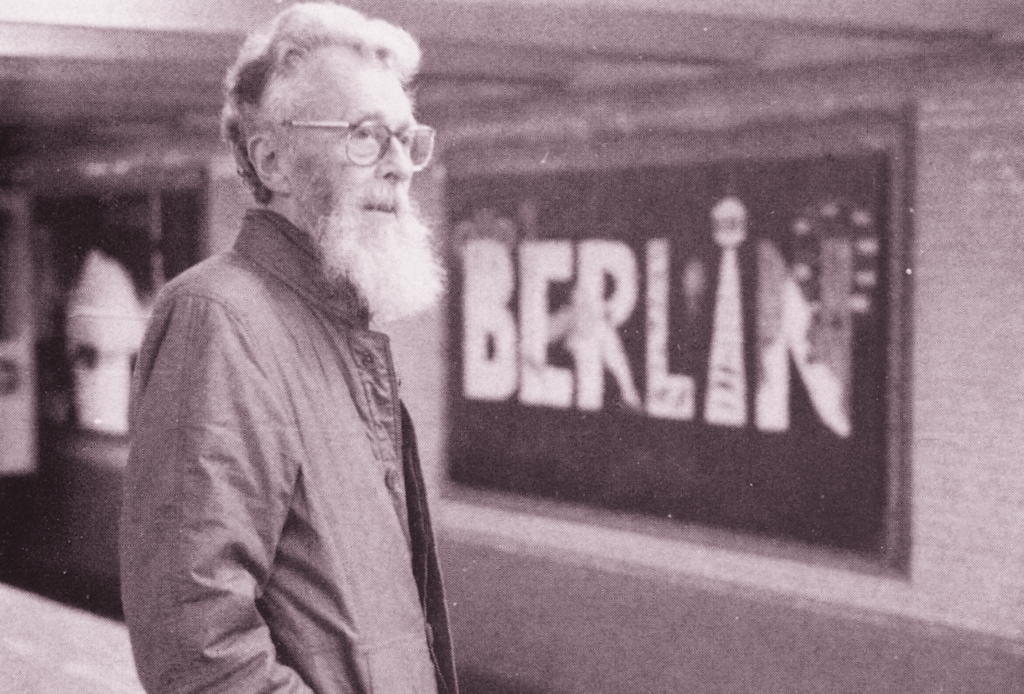

Peet in the Berlin metro, a few months before his death in June 1988. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

Peet in the Berlin metro, a few months before his death in June 1988. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

A life story, with holes

At that stage, Peet was also working on his memoir.

“His account is strangely superficial and anecdotal,” says historian Stefan Berger. “As the Independent put it in a review of the book: ‘The man and his times are fascinating. John Peet leaves many questions unresolved.’ ”

Indeed, Peet’s vague autobiography leaves the reader rather puzzled. For one thing, his supposed past as a sleeper agent for the Russians doesn’t add up to anything—that is, unless he was withholding details of assignments he may have had through the years in Palestine, Vienna, Warsaw or Berlin. He never ever mentioned anything about it even to his closest family.

“According to his brother Stephen, the London-based filmmaker, Peet only came up with this story after his publisher asked him to rework the manuscript of his autobiography,” says Berger, who interviewed Stephen Peet in 2001.

“When he learned he had incurable cancer, he added to the draft the information that when he was with the International Brigade in Spain in the ’30s he had been recruited as a spy by the NKVD, the Soviet intelligence agency,” explains ex-general manager of Reuters Michael Nelson.

Could it be that Peet, a very sincere man, upon learning that he’s on his way out, confessed about his past in order to put it to rest? Very likely. Nelson, though, has another theory.

“He may have thought the disclosure might have made it legally dangerous to visit the UK,” explains Nelson. “The danger may have been remote, but why take the risk?”

The question of whether Peet’s claims, relentlessly denied by his family and friends, were an intricate put-on, a preposterous fantasy—or, in the strangest scenario, true—was never answered adequately by him. Peet died in his sleep on 29 June, 1988; he was 72. His memoir, The Long Engagement: Memoirs of a Cold War Legend, was published the following year in London.

Eighteen days before passing away, Peet sent a letter to his good friend Paul Moor, an American journalist who befriended him while working as a Reuters correspondent in Berlin. Peet had one last secret to share, which left Moor “astonished.”

Peet wrote that he had a “revealing thought which I would now rather share with you than with anyone else.”

“It is not a thought that plagues me day and night, but it does every now and then. As you probably know, in Spain a unit of the same secret service, who had chosen me, hired a man for a real job. He was an officer in the Republican army, a Spaniard. With the papers of a—probably fallen—member of the International Brigade, he crept into the Trot.-circles. [Author’s note: Trot. is evidently an abbreviation for Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, used for camouflage before the East German censorship.] Afterward, he went to Mexico to work with his little ice ax.”

Peet was referring to Ramón Mercader, a Spanish communist and an agent for the Soviet secret police NKVD. In 1940, using the passport of a Canadian who died fighting during the Spanish Civil War, Mercader went to Coyoacán, a village outside Mexico City, and killed Leon Trotsky with an ice pick.

“And now to the part that worries me,” continued Peet, ”to the hypothetical question: Had I been given such an order, would I have done it, I, who, like millions of others, had committed to the battle, believed in it? Sometimes, in the middle of the night, I’m overcome by the terrible thought that I would have done it.”

The headstone of John Peet in the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery in Berlin. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

The headstone of John Peet in the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery in Berlin. Credit: Jordan Todorov and archive of Victor Grossman

Note: John Peet’s widow, daughter and son declined multiple interview requests for this story.