Before John Waters was a household name, he was a code word. Knowing it meant you were one of the trash cognoscenti, in tune with the underworld where pre-Stonewall gay culture was relegated, as being homosexual was literally a crime according to the state. Whether you think his movies are a crime against cinema or cherished treasures, every one of them was an act of guerrilla filmmaking and therefore a crime caught on film. And censors tried to make showing some of them a crime as well.

Before Serpico, NYPD raided bars on the regular, whether their bribes were paid up or not. When the politicians needed to show they were doing something to “clean up” New York City, police raided the gay bars, at least until a protest led by trans women of color at the Stonewall fought back. Before then, gay and underworld were synonymous, which is one reason noir stories were one of the few places to find LGBT characters. Films like Midnight Cowboy and Pink Flamingos, which acknowledged our existence, were banned by censors and depending on where you lived, had to be smuggled in for secret viewings.

Being a Friend of Divine didn’t always mean you were a Friend of Dorothy, but if you were a fan of John Waters and the Dreamlanders, you were at least a Friend of a Friend of Dorothy. Seeing these films used to be a quest; you might see a midnight showing of Pink Flamingos at a porno theater—it was Rocky Horror for the self-proclaimed freaks—or once the infamous film was released on VHS, you had to ask the employee at the video store to get you the tape from behind the counter. At least I did at Curry’s Home Video, the Kim’s Underground-equivalent of the New Jersey suburbs. You didn’t have to ask for the Faces of Death films, for comparison.

John Waters has a career trajectory the opposite of artists who made their mark with shock. His biggest hit is still outrageous, but each one after it became progressively more wholesome (yet subversive) so that his latest and possibly final film, A Dirty Shame—in which Tracey Ullman and Johnny Knoxville play sex addicts—feels almost quaint and adorable. Pecker, which despite its title is neither about penises nor chickens, is a fun takedown of the art world that somehow lassoes in drag kings, voting booth sex, Catholic Mary cults, and rough trade bars, but still feels like a family film a la Little Miss Sunshine. But every film prior works as a crime story, and the best introduction to them is to watch them in reverse chronological order.

Cecil B. Demented is about a group of film school terrorists who kidnap a film star attack the film set of a Forrest Gump sequel. It’s a fun flick for lovers of cinema—as Marty Scorsese would say—but not the best entry into Waters-world. The place to begin is with his violent paean to suburban psychopaths, Serial Mom.

Kathleen Turner plays perfect mother Beverly Sutphin, who will do anything to protect her family. She also loves to torment her neighbors, specifically Dottie Hinkle, with obscene phone calls and other cruel pranks, as retribution for minor peccadilloes. John Waters took the ridiculous penchant of cartoon psychopath Hannibal Lecter caring if people were rude and ran with it, giving us a husky-voiced Donna Reed stereotype who will literally gouge out someone’s liver if they wear white after Labor Day. John Waters is a true-crime fanatic, having sat in the courtroom for infamous murder trials, taught writing to inmates, and corresponded with members of the Manson Family. Serial Mom skewers our cultural romance with psychopaths, but our love of true crime stories and turning slaughterers into celebrities. Not only does Beverly Sutphin kill teachers and do-gooders who interfere with her family, she becomes a celebrity herself as the trial is made into a national sensation. Made shortly after the Pamela Smart case and the O.J. Trial, Waters digs deep into the satire on this one, and it’s easily the most accessible of his films has crime chops. (One might make a crime-story case for his most famous film, Hairspray, which takes aim at the racist hypocrisy of the segregated ‘60s rock ‘n roll era, and it is certainly worth seeing, but if you’re waiting for someone to get executed for the crime of Assholism, you’ll be disappointed.)

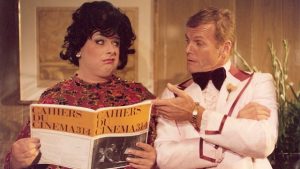

Next up is Polyester, his love letter to Douglas Sirk films and Herschel Gordon Lewis. Remembered for its Odorama scratch-and-sniff cards handed out to audiences, this is his domestic suspense crime story, where embattled wife France Fishpaw suffers the indignities of a philandering husband—who runs a porno theater and relishes the protesters perpetually on the lawn of their suburban home—and two troubled children, including a daughter who’s dating punk Stiv Bators of The Dead Boys and The Lords of the New Church, and a son with a foot-stomping fetish who is terrorizing women all over Baltimore. Then Todd Tomorrow shows up—played straight by gay Hollywood heartthrob Tab Hunter—and whisks Divine off her sore, unappreciated feet and gives her the love she craves. But fitting its melodramatic plot, it’s all a ruse to get her mother’s inheritance, and she’ll only be saved by her children’s terrible vices. It’s a family film at heart.

Crime Towns are a staple of the pulp genre, from the crook’s fantasy turned nightmare at the end of Jim Thompson’s The Getaway to Poisonville, the corrupted town in Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest that spawned a thousand imitators (including Akira Kurosawa). In Desperate Living, frazzled wife Peggy Gravel and her nurse Grizelda Brown kill her abusive husband and are exiled to Mortville, a junkyard town of misfits run by Queen Carlotta and her daughter, Princess Coo-Coo. Divine was off doing something else at the time. Waters even pays homage to the scene in Yojimbo where a dog walks across the street carrying a severed human hand in its mouth, and I won’t ruin the gag for you, but it’s not a hand this time. Peggy joins forces with the Queen, and the town’s denizens, led by Mink Stole as lesbian wrestler Mole McHenry, take down the evil Queen in a Freaks-inspired revenge spree that ends with her roasted like a pig and Peggy executed with a .38 caliber suppository. Desperate Living is low-budget, sleazy, and intentionally offensive, so if it turns you off, you should stop here and watch Hairspray instead. The next two films amp up the shock value to lethal levels.

The most straightforward crime film in the Waters oeuvre is Female Trouble, perhaps inspired by his quote about how in the criminal world, getting the death penalty is akin to winning an Academy Award. This one sends up ‘50s “bad girl” pictures, where one little moral peccadillo snowballs into a sinful life of crime and a horrible end. Divine plays Dawn Davenport, a bratty juvenile delinquent who wants a pair of cha-cha heels for Christmas, and throws a violent tantrum when denied. This leads to murder, celebrity, and of course, execution by electric chair. Dawn flees home and gets pregnant the first time she has sex, bearing a thankless daughter who rebels against her criminality and threatens to join the Hare Krishna cult. It’s a twisted send-up of Mildred Pierce and Imitation of Life, leading to Dawn disfigured by an acid attack, performing a bizarre nightclub act, where she strangles her daughter onstage after she fulfills her threat to become a peaceful chanting hippie. It’s a like a Catholic nun’s tirade against girls who wear lipstick come to life, and Dawn thanks her fans before she’s electrocuted to death.

If you’re still game, the still-infamous Pink Flamingos, an exercise in bad taste, is your nasty dessert. Like many artistes who think they’ll never get another chance at bat, Waters swung for the filth fences with this one, and it paid off. The meager plot involves filth queen Divine and her family of weirdos vying with two revolting newcomers—The Marbles—who wish to defeat them for the title of Filthiest People Alive. The movie is a dirty bomb planted beneath the parliament of middle class mores by the Guy Fawkes of Filth. The vile Marbles make their living by kidnapping lesbians and artificially inseminating them against their will with the seed of their gay limo driver, and selling the babies on the black market. Divine and family are thieves and robbers, living off their ill-gotten gains like the cannibal Sawney Bean family of sixteenth-century England. When someone calls the cops on their party, they descend upon the lawmen with cleavers and devour them alive.

Divine declares total war after the Marbles fire a fecal shot across their bow by mailing her a fresh turd, inspiring the immortal line, “Someone has mailed me a bowel movement!”

It descends into a Dante’s Inferno of debauchery, with simulated incest, sex while a chicken flaps all over the bed, the aforementioned rapes, a talented trumpeter with a singing sphincter, and the revolting final shot where Divine eats a freshly deposited dog turd to cement her status as the undefeated Queen of Filth.

It’s exactly what a bunch of weirdos on acid who loved Andy Warhol, exploitation films, and art house dramas might come up with if they decided to create an all-out assault on the American senses. They got the reaction they wanted. It kicked off John Waters’s career and led him to Broadway, a Simpsons cameo, and a jury seat at the Cannes Film Festival. So, if you’re thinking of saving the “good stuff” for later, take a hint from Waters and fire your load early and make a splash. There’s no such thing as bad publicity, and fifteen minutes of fame can stretch into decades if you know how to milk it. John Waters knew.