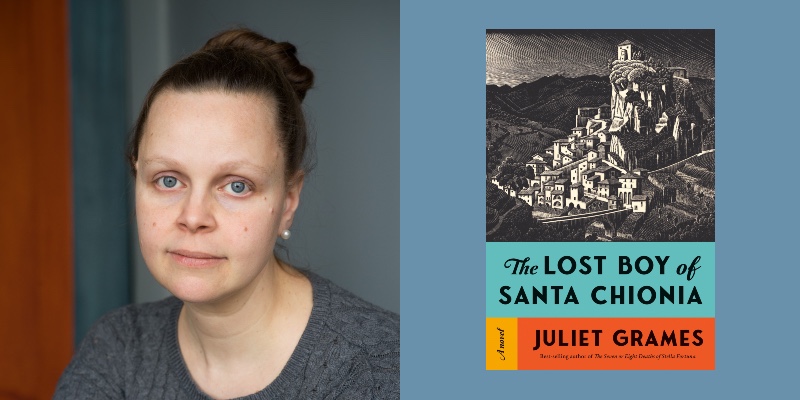

Juliet Grames: Immigrant Detective. It’s not an official title, nor does it rank among the distinctions listed in her biography (though maybe it should). Those include Editorial Director at Soho Press, for which she received the Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America, and bestselling author of historical fiction. Her debut novel, The Seven or Eight Deaths of Stella Fortuna (2019), was shortlisted for both the Connecticut and New England Book Awards and won Italy’s Premio Cetraro for Contributions to Southern Italian Literature. Her newest, The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia (July 23, 2024; Knopf), was named a Best of Summer Staff Pick by Publishers Weekly. Both stemmed from her research into the Italian immigrant experience.

Having grown up in a large, tight-knit Italian-American family herself, Grames learned the importance of preserving legacy through storytelling early on. It began with a desire to better understand her grandmother, who awoke fundamentally changed following a lifesaving lobotomy. Grames donned her detective’s hat and went down the research rabbit hole in search of the answers nobody could provide, even taking a leave of absence from her job to spend a winter in the Calabrian village where her grandmother was born. The eventual result was The Seven or Eight Deaths of Stella Luna, which fictionalized her grandmother’s life story while also honoring the sacrifices and struggles of all foremothers who suffered to ensure a better life for their children.

One disconcerting fact that Grames turned up was just how frequently male immigrants had gone missing in their own pursuits of advancement. This would later inspire The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia, which isn’t a traditional crime novel but one that incorporates elements of the genre. The year is 1960, and fiercely independent American Francesca Loftfield has journeyed to a (fictional) Calabrian village to open a children’s nursery. But when a set of unidentified skeletal remains are unearthed in the aftermath of flooding, she finds herself agreeing to investigate on behalf of a bereaved mother whose son went missing forty years ago. An amateur sleuth by circumstance and skill set, Franca then embarks on a harrowing search for truth that also proves quite revelatory for her own self-discovery.

Now, Juliet Grames talks about making fiction fit facts in her historical mystery …

John B. Valeri: The Lost Boy of Santa Chionia isn’t a traditional crime novel but a novel with crime in it. How did the notion of unidentified remains serve as a catalyst for the book’s plot – and in what ways do you think the lingering questions surrounding that discovery enhance the story’s overall potency?

Juliet Grames: This novel grew out of my research work in the Italian immigrant experience—during the course of writing my first novel, I often felt like I had become an immigrant detective myself: trying to track down missing pieces in family stories across the diaspora. One thing I learned was how frequently immigrant men have gone missing, never to be heard from again. I hit upon the idea of using the unidentified skeleton as a platform for exploring the various reasons immigrant men go missing.

I did really enjoy inverting the structure of a murder mystery here—I wanted the puzzle mystery aspect to be a true brainteaser for Golden Age fans, and beginning with unidentified remains allowed me so much runway to build up that puzzle. It wouldn’t be a whodunit because the goal wasn’t to find out who committed the crime, it was to figure out what crime had even been committed (and why it had been so painstakingly covered up by so many people that human remains would go unidentified).

JBV: Francesa Loftfield can be considered something of an amateur sleuth. What of her character and circumstances lend themselves to investigating the missing persons she hears about – and how does her role as an American school teacher help to legitimize her inquisitiveness?

JG: Francesca’s character was partially inspired by a real historical personage, Ann Cornelisen, an American writer who spent the 1950s and 1960s working for Save the Children in southern Italy, where she opened nursery schools in impoverished villages. While researching my historical novels about Italy, I’ve reread Cornelisen’s memoirs many times (check out Torregreca or Women of the Shadows if you’re interested in what living in Italy during this period was like—both excellent reads). One aspect of Cornelisen’s day-to-day life in a village was being asked to help out with things that were completely not in her professional purview. She was an educated woman with resources; she also had special access to all the power structures of the village, like a friendship with the mayor and rights to go through sensitive town records (censuses, income, and property reports) on behalf of her charity organization. Villagers knew this, and came to her to help out with things no one else could—or things no one else wanted to help with. I thought all these qualities were exactly what my de facto immigrant detective protagonist would need: access to public and private records; the knowledge and chutzpah to work the system; and above all, a reason for getting involved in things that were really none of her business.

JBV: While the village of Santa Chionia itself is fictional, you’ve visited Calabria in Southern Italy. How did setting foot in the land itself inform your ability to render a palpable sense of place – and in what ways did creating an imaginary landscape liberate your storytelling?

JG: The town of Santa Chionia grew out of my obsession with Africo, a real ghost town in the Aspromonte mountains, which was forcibly depopulated in 1950 after a flood. The history of Africo is fascinating and extremely troubled, and I felt an urgent need to try to capture the drama so it wouldn’t be forgotten by time—that’s the trouble with depopulation: you remove everyone from a place and there’s no one left to tell its story.

I chose to invent Santa Chionia—a neighbor of the historical Africo—so that I could borrow aspects of that true history but would have the freedom to invent the particulars of a murder mystery without accidentally treading on real and living trauma. Over the course of three research trips, I was very fortunate connect with generous people from Africo—in particular the great Calabrian writer Gioacchino Criaco, who took me to visit the ruins of the ghost town—as well as other fascinating villages in the area. I tried to absorb extraordinary details from all of them and stew them into one imaginary town that reflects their shared and singular experiences.

(Read the article Grames wrote about the journey to that ghost town here, in CrimeReads.)

JBV: To expand on that: the book is set in the early 1960s. What was your approach to establishing an authentic sense of people and their daily lives (culture, language, food, etc.) – and how did you then balance creative license with an overall fidelity to realism?

JG: Oh geez, I just love research. For me it’s not balancing creative license and fidelity to realism—it’s the opposite. The more desperately I cling to research-sourced data points, the more creative energy I feel inside a scenario. Historical research largely imposes limitations (although yes, it also presents surprise possibilities!) on what your character can do. When you learn how scarce grain was in the mountains, you realize your Italian characters can’t lazily be eating pasta or bread all the time—now you need to figure out how to feed them, authentically, with lentils, goat cheese, and acorns. All that takes a lot more research, but it also makes every scene a little more interesting. Plus historical authenticity adds plenty of potential conflict to your character’s day-to-day life, and we’re all looking for conflict, right?

JBV: The challenges Franca faces (or witnesses) – bigotry/sexism, civil/political/religious unrest, corruption, domestic violence, poverty, etc. – still exist in contemporary society. Was there a conscious intent to mirror the current climate or was that something that developed more naturally as the story played out? Also, how can fiction be used as a more palatable lens through which to view real-life issues?

JG: You know, I couldn’t stop myself from channeling a lot of contemporary allegory into this story. It wasn’t that I set out to do that: it was that I loved the research points, and cherished the personal stories that came out of my interviews and my reading, and I just couldn’t avoid how much those stories chimed with all of the things I was worried about in my own modern life. Historical fiction should always give us a lens for looking at ourselves. You don’t have to try to make it do that; you just have to be faithful to the historical aspect and the universal truth exerts itself unavoidably.

JBV: An unexpected flirtation causes Franca to ruminate on her past loves and losses as she considers a new romance. How did juxtaposing current day events with remembrances of her haunted history allow for an organic sense of character development – and why is an understanding of those seminal experiences important as she forges ahead with a new role and relationships?

JG: Writing the narrative that way—looking back while looking forward—felt natural to me because that’s how I live my life, often lost in thought about the ramifications of past choices while I am making decisions about my present.

JBV: You are an Editorial Director at Soho Press, which allows for unique insights into the business aspects of publishing as well as collaborating with authors. How have you found that to help in your own career development, both in terms of craft itself and your relationship with your editor (and receiving editorial feedback)?

JG: I am so grateful for my time spent editing novels because it taught me how to edit my own novels—and in my opinion, editing is at least 80% of the work of writing. I’ve had so much opportunity to think deeply about other people’s storytelling, and to experiment with them on how to improve on what one starts with. Being an editor is what got me to being a writer, even though I originally thought it was the other way around.

JBV: Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

JG: I’m two years deep in research for a mystery novel centering around a musician who disappeared during World War One in Italy—two more obsessions of mine!