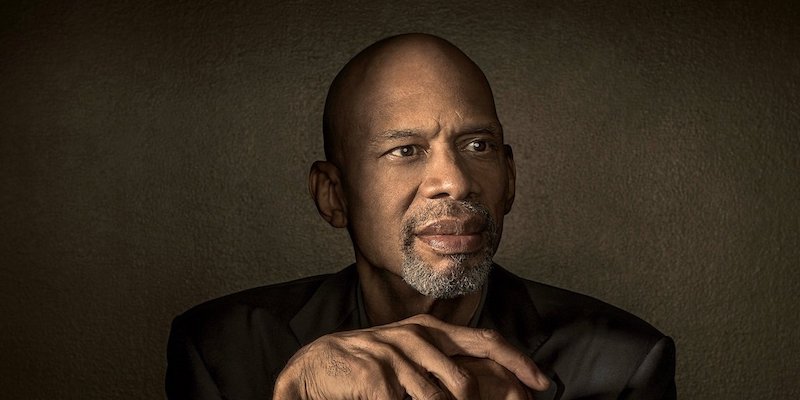

Not to dwell on this subject, but I was a fan of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar long before he started writing Mycroft Holmes novels—he was already incredibly accomplished, I have watched many a “skyhook,” and his political commentary is always apt and insightful. It’s such a pleasure to read his and Anna’s work, and it’s also a joy to have the opportunity to chat with such a lovely person—I embarked on this interview writing about 700 questions, thinking he could pick and choose. But they’ve all been answered and as a fellow author of historical fiction, I’m especially glad to share a conversation about culture, and connections, and writing the people who were erased at the time.

Lyndsay Faye: First off, thanks so much for speaking with me again! It’s a wonderful book and I was thrilled to get an early read. Your previous effort, Mycroft Holmes, received very favorable reviews by both Sherlockians and historical critics. How did you try to up the ante for the sequel?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: The biggest change in the two books is that in Mycroft and Sherlock, Mycroft is dealing with some unexpected physical impairments that put his life in jeopardy and keep him from being quite as active as he was in the first book. And, because he keeps these ailments a secret from both Sherlock and his best friend Cyrus Douglas, we see how Mycroft begins to go his own way, keeping secrets, and doing what seems best to him. He’s also much more confident in his mental acumen than he was in the first book. (In the first book, he was engaged, in love, and much more innocent.) And, because his ailments force him to be more sedentary, the plot is more “twisty” (as our editor put it) than the first one.

LF: In your first book, a large percentage takes place in Trinidad, which is relevant to your own cultural history, while Mycroft and Sherlock occurs almost entirely on more familiar ground for readers of the Holmes mysteries, in London. Did this produce any new challenges for you and Anna?

KAJ: It posed the same challenges as the first book, in that it always requires a lot of research. Whether he’s in Port of Spain or in London, we need to know what he sees, what he hears, and even what he smells: how he travels, what he wears, what he’s likely to eat, and so forth. In other words, it’s his era, not ours. If anything, it’s more difficult to get it right in London, because there’s more material on “how it was,” which is sometimes contradictory. We’ve been praised for research in these two books, particularly from Sherlock Holmes aficionados. We feel we owe it to them and to ACD to do right by the characters he created.

LF: It’s obvious from the title that unlike the first installment, Sherlock Holmes plays a major role in the sequel. How did you go about reasoning backward to what he was like in his late teens? Did you make deductions about his raw, emerging personality from any particular clues or adventures?

KAJ: We tried to take into consideration every story of Sherlock, rather than one or two. As anyone who has ever read ACD knows, Sherlock is not a robot or a “high functioning sociopath” or an addict. He is multifaceted, with very real emotions. He shows both humor and brittleness. He can show addictive behaviors as well as extreme discipline. That’s what we tried to show.

LF: Speaking of developing characteristics, obviously Mycroft is still the main protagonist, and he’s slowly changing from a young, dynamic individual to “one of the queerest men” in London. In fact, his character is so powerfully drawn by Doyle that he’s beloved despite only appearing in two cases. So you had a very great deal of leeway regarding his early life. Did that make your task easier or more difficult?

KAJ: We didn’t have much to go on, so we took everything said about Mycroft in ACD as gospel. We hope that our readers realize that: and that they will trust us to “get there” when it comes to Mycroft’s eventual obesity and sedentary nature, his co-founding of The Diogenes Club and the rest of it. But what a person is in his 20s isn’t necessarily what he’ll be in total when he’s in his 40s. We are excited about how to get him from here to there. We have a lot of room to work, in other words.

LF: Your and Anna’s combined style make for some truly vivid and atmospheric prose. Do you have a set process for this, or a certain allocation of duties? Was it easier the second time? Because the results in both books are superb.

KAJ: Thank you. As both of us have expressed before, we have different strengths. I am a history aficionado. She likes research. I like storytelling in terms of plot. She likes writing dialogue. We both like interpersonal stories, and we’re both interested in making a bit of social commentary when and if we can. It also allows us to show how societal problems and successes had their roots in earlier societies. For example, Dr. Watson was wounded in Afghanistan, and right now American, British and Canadian troops are still fighting there. As for “easy”….no, it’s never easy, not then, and not now. But there’s a lot of joy in it.

LF: Drug use plays a major role in Mycroft and Sherlock, and indeed it shaped the history of the entire British Empire in some fashions. Yet there are some today who still insist that Sherlock Holmes only ever dabbled in drugs out of pure boredom. What’s your opinion on the subject, if you have one? Was Holmes exhibiting addictive tendencies, or playing the purely intellectual scientist?

we show Sherlock as pursuing drugs simply as a means to an end, not because of any particular attraction or addiction. He isn’t old enough or bored enough to indulge just for the sake of it.KAJ: So far, except for tobacco and a kinship to Vin Mariani (a popular drink of the time that was infused with cocaine), we show Sherlock as pursuing drugs simply as a means to an end, not because of any particular attraction or addiction. He isn’t old enough or bored enough to indulge just for the sake of it. He’s not the typical addict because solving crimes is much more addictive to his personality. He’ll gladly get rid of the drugs to chase down a criminal.

LF: It’s almost impossible to think of the canonical Mycroft as a romantic being, but we learn from you that he wanted a wife and family very much. How important to you was this aspect of his character? Did you expect it to throw the reader off balance somewhat, challenge our expectations?

KAJ: ACD was able to write two characters who were celibate, at a time when no one would question how or why. It was a different era. We really didn’t think we would have that ability to simply ignore whether or not Mycroft, in his early to mid-twenties, had any interest in romance. So, we had to work backwards, in a sense. Why didn’t he have a romantic interest? Why was he obese? Why was he sedentary? We decided to try to explain why that would be. Having his heart broken (like in book one) really determined a lot about him.

LF: Your historical verbage and detail are both spot on, and I speak as one who knows! Did you and Anna come across any incredible tidbits that didn’t make it into the novel? When is the research enough, and you’re ready to start the writing process? What are your major sources?

KAJ: We came across a lot of tidbits that didn’t make it in, mostly because our editor, Miranda Jewess, is terrific at spotting those “info dumps” that tend to say “here is the writer doing research”! As for our sources, we had many. Beyond a lot of internet searches in general (where one thing leads to another) and every novel and short story by ACD, our go-to books include Victoria by Stanley Weintraub; Victorian London by Liza Picard; The Concise History of Costume and Fashion by James Laver; and Yin Yu Tang, the Architecture and Daily Life of a Chinese House by Nancy Berliner. And of course Dickens.

LF: In both books, a number of key characters are people of color, and in Mycroft and Sherlock, we explore the world of Chinese immigrants and drug purveyors (which was of course perfectly legal as long as they paid their taxes). To what extent do you feel like historical fiction now gives us the opportunity to get to know people who would have been marginalized in stories written during the time period? One of the few similar characters in the Doylean canon is “the rascally Lascar” from “The Man With The Twisted Lip,” who isn’t even dignified with a name. Are you telling the stories of people who’ve been culturally and historically erased?

KAJ: In reading about this time period and Holmes, they never show how the “other people” of the British Empire interacted, even though they were there. It gives us something to exploit and explore that maybe other writers didn’t think about. I think that’s a real bonus to writing these Holmes pastiches: the ability to shed a light on people who’ve been marginalized and kept in the dark. That’s important to both my co-writer and me. We also try to stay true to what Sherlock would have thought of people of color or the lower classes at the time, and there are a few ACD stories that point to that. We give Mycroft a bit more leeway, because we’ve created a black best friend, but with him too we’ve tried to stay true to the era.

We like seeing justice done: and both Mycroft and Sherlock are out to get justice, though in different ways. So we’re happy to see them championing children.LF: Speaking of erasure, children at the time—especially street children—were considered largely disposable, a fact which Cyrus Douglas takes very seriously. Children were also being targeted in Mycroft Holmes. Is this an important historical theme for you?

KAJ: Yes, we wanted to particularly highlight children, because they’ve been used too much as set pieces in stories of the era, though there are some great and noteworthy exceptions (David Copperfield comes to mind). The British psyche thought of them as a people apart. We’re also interested in detailing how those with no power, whether they be lower classes, immigrants or children, are often abused by those with power. We like seeing justice done: and both Mycroft and Sherlock are out to get justice, though in different ways. So we’re happy to see them championing children.

LF: It’s always grand fun writing sibling squabbles, and the ones between Mycroft and Sherlock are delightful. Do either of you have siblings? Were these drawn from any personal experience?

KAJ: Both Anna and I, as it turns out, are only children. Which I guess is why we can come up with good feuds and fights, because we can conduct both sides in our heads and we were never shot down by the real thing!

LF: Finally, even while knowing it’s maddening to be asked this before a book is even published, are you planning on a nice round trilogy? Or even continuing open-endedly?

KAJ: There’s no trilogy, because each of these books is independent. You don’t necessarily have to read Mycroft Holmes to read Mycroft and Sherlock. (Though we hope you will!) But if you’re asking is there a third book in the works, the answer is yes. We are writing it right now, and if all goes well, it will come out at the end of next year.

LF: Many thanks for chatting, and best of luck with Mycroft and Sherlock!

KAJ: Thank you for giving us this opportunity, and for reading the books!