I grew up loving mysteries—I can still picture those yellow-spined Nancy Drew books that were integral to my childhood—but it wasn’t until much later that I began reading thrillers. There’s something so delicious about picking up a book that mashes together fast pacing, an intriguing mystery, and the rush of danger. I love flipping pages as my heart beats wildly, desperate to find out how the characters will (hopefully!) escape a perilous situation or win their showdown with the villain and save what matters most to them.

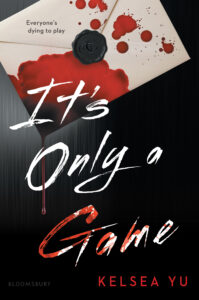

It’s Only a Game was the first thriller I wrote. I knew from the start that my main character, Marina Chan, would be on the run from a dangerous past. To someone in her situation, a safe haven—a physical place she loved and found shelter in—would be one of the things that she would care the most about. In my evil thriller writer thoughts (mwahaha!), I needed something the villain could threaten—something that Marina would sacrifice a lot to save. I picked a restaurant without thinking too much on it, but looking back, my association between restaurants and comfort make complete sense.

In my family, food is a love language. My mom is a fantastic chef, and while she cooks a variety of cuisines, Chinese food is her specialty. She learned from her mom who, in her heyday, could cook up a restaurant-quality feast for twenty relatives in one afternoon, every dish made from scratch. My fondest memories of visiting my mom’s family involve sitting with my aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, parents, and brothers, passing dishes, conversing and eating Ah Ma’s delicious food while she looked upon us all with a contented smile, encouraging us to eat more.

On my dad’s side, my childhood memories include attending massive reunions where we’d take over part of a local Chinese restaurant, filling up five or so banquet tables with extended family. My brothers and I would always be at the “kids’ table,” which included cousins (various levels of removed) from age five to others well into their twenties. Dish after dish would arrive on the turntable, and we’d stuff our faces until some auntie inevitably came around to collect any unused moist towelettes and, if we were lucky, hand out red envelopes.

My dad’s parents also owned a tiny Chinese takeout when they first moved from the Philippines to the United States. My mom’s sister opened and ran a Chinese restaurant for several years that gathered a rave review in the New York Times before she sold it. And my mom’s aunt had a bakery in Taiwan (where my mom’s family lived before immigrating to the United States) for years. Chinese food and restaurants are in my family. And yet, when I first wrote a restaurant—Marina’s safe haven—into It’s Only a Game, not once did it occur to me that I could make it Chinese.

As many fellow diaspora members know, it is only in recent years that our stories have begun to make their way onto bookshelves in English language markets like the United States. I grew up an avid reader, but with the exception of Amy Tan, I didn’t read any Chinese American characters written by Chinese American authors. To say “I didn’t dare write Chinese American culture into my stories” would be inaccurate. While that may have been an underlying truth, it honestly wasn’t even something that crossed my mind. I’d had so little representation that it took me ages to consider writing Chinese American characters; I didn’t think much beyond that.

It’s Only a Game has gone through a long and winding journey, which included two full rewrites and additional edits. Between initial concept and final publication, seven years passed. In that time, more Chinese American-authored books started getting published, and I began to question my own decisions in what specific elements I had chosen to incorporate in each of my stories. And, more vitally, what I hadn’t.

After signing with my publisher for It’s Only a Game, my editor and I underwent a large revision to the book. It was an unexpected but welcome opportunity to turn Marina’s story into more of something I’d write now. In earlier revisions, I had already begun to weave in more elements of my culture and personal identity into the book. Now, I added in past scenes where Marina learns Mandarin, where she meets other Chinese American kids, where she goes to Saturday Chinese school, where her Chinese tutor talks to her about what it means to find community.

Still, it wasn’t until a few weeks before I turned in my big revision that it suddenly occurred to me that I could also change the restaurant to be Chinese. My editor was on board, and thus, Bette’s Battles and Bao—a mix between a Taiwanese Chinese restaurant and a gamer café—was born. Everything about it is an homage. Bette is named for Bette Bao Lord, a Chinese American writer and activist. Jimmy, her husband, is named for my late paternal grandfather, who ran the Chinese takeout. They serve Chinese and Taiwanese food as a nod to my mom and my Ah Ma.

Bette’s Battles and Bao felt like the final piece clicking into place to make It’s Only a Game feel right and true to me. I couldn’t be prouder of the story it is today, and in a funny way, I’m grateful for its long journey to publication, because it gave me the chance to tell a story that is the best version of itself. When Bette’s comes under threat, it’s more than the possibility of losing a home. It’s Marina’s unofficial adoptive parents and budding new connection to a healthy Chinese community at risk. It’s a place that carries meaning to her in countless different ways. And I hope that shines through.

***