The serpent was the most cunning of the beasts and tempted Eve to eat the fruit. She gave the fruit to Adam and he ate, too. Then their eyes were opened, and they saw they were naked.

Just so, a snake figures prominently in The Lady Eve—a Brazilian snake, called Emma—along with a woman who is sometimes called Eve; and after the woman “clunks” a man on the head with a piece of fruit (using the traditional though nonbiblical apple) he soon enough begins to fall, not once but six times. He’s also conked on the head twice more (by a large hat box and an entire coffee service), gets a carving roast spilled over him with all its gravy, and is interfered with by a horse. It’s a sophisticated comedy.

That unquestionable sophistication is apparent first of all in the settings of a luxury cruise ship and a Connecticut mansion—the sort of milieu in which Hollywood often placed its stories, but which Sturges, almost alone among Hollywood filmmakers, had known firsthand. (He lent his own silver service to the production, to ensure authenticity.) The Lady Eve is sophisticated, too, in its tone of wised-up elegance, which Sturges dared himself to sustain even while setting off ostentatious flurries of slapstick. I might talk about this peculiar merger of the elevated and the vulgar as central to Sturges’s art; but that, for the moment, is not my subject. I am more concerned with another matter, though one that I think is related: why Sturges pressed a biblical text into the foreground of The Lady Eve and then made its meaning obscure.

One thing is clear: His mapping of the contours of Genesis onto the terrain of The Lady Eve accounts for some of his wised-up tone. A rube audience—to characterize such a group no more delicately than Sturges might have done—would have taken offense even at the opening credits, which reduce the instigator of Man’s first disobedience to an animated cartoon serpent, grinning, top-hatted, and rattling a maraca in its tail. A more urbane audience soon notes that the overlay of scripture is not only irreverent but also noticeably uneven. In some places— sequences where physical indignities multiply, for example—the map seems to have bunched up, so that you witness the fall and fall and fall of Man. Elsewhere, the biblical features simply give out before the movie’s borders are reached. There’s hardly a snake to be seen or heard about in the entire second half.

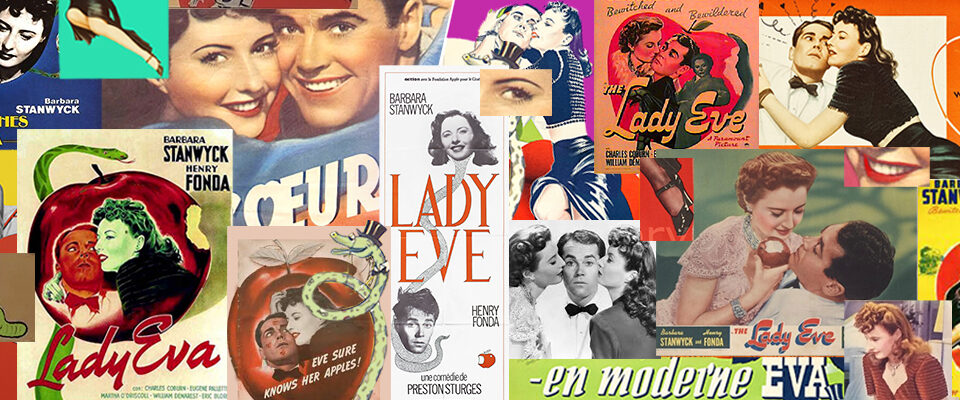

The Lady Eve begins as the story of a man who not only believes he’s found Eden but thinks he can leave it and come back later.Most puzzling of all are the inconsistencies between the Bible’s characters and the movie’s principal figures: Barbara Stanwyck as the adventuress Jean, or sometimes Eve, and Henry Fonda as the studious but none-too-bright brewery heir Charles, or sometimes Hopsie. A large body of critical writing has grown up around these two and the movie they inhabit, which is widely admired as one of the best ever made in Hollywood and one of the most thoughtful. As Stanley Cavell showed in Pursuits of Happiness: The American Comedy of Remarriage, you can even make philosophy out of The Lady Eve. Think about the typological parallels that Sturges forces on you, though, and you find that the most basic questions remain unresolved.

If Jean is to be compared with the biblical Eve, why would it be such a waste of effort to tempt her? Not that anyone tries; she sees through all illusions right from the start and already knows plenty about good and evil. And yet, in a blatant departure from the Bible, this sinful trickster is the one who flees from snakes, while her gullible Adam professes that “snakes are my life.”

Charles is so mad about the creatures that another character calls him a snake. (This slur is uttered by Charles Coburn as Colonel Harrington, Jean’s putative father and confederate in card sharping and con games.) How can it be that the film’s Adam, after all his tumbles, should ultimately remain impervious to disillusionment, bouncing back up as the nickname Hopsie suggests? He does not end in chastisement but instead regains the state of innocence in which he began—only now (again to the likely discomfort of the rubes and the righteous) he is much, much happier.

I might put aside these questions and simply enjoy The Lady Eve were it not for the film’s production history, which suggests that any discontinuities were purely intentional.

Sturges wrote the first version of the screenplay on assignment from Paramount from September through December 1938; responded to a detailed and highly intelligent memo sent in January 1939 by the producer, Albert Lewin; thoroughly revised the script from August through early October 1940; and then put that draft through another eleven-day rewrite to achieve the third and final version. By then, whatever may have seemed casual or offhand in the script was nothing of the kind, but rather a calculated pretense of randomness.

Why would Sturges want such an effect? Why did he ignore, for example, Lewin’s objection that there was no compelling reason to make Charles an expert on snakes? (As a sign of Charles’s pedantry, he doesn’t call himself a zoologist or even a herpetologist. He insists on ophiologist.) These questions make me suspect that the mismatch between the Bible story and The Lady Eve may tell us something about the relationship in Sturges’s work between writing and directing, text and image. I also suspect that the mismatch is intimately bound up with the film’s interplay of literal-mindedness and imagination, wiliness and credulity, knowledge and innocence—even, perhaps, prose and poetry.

To trace the answers, I might begin with an anomaly. As Brian Henderson points out, The Lady Eve is unique among Sturges’s major films in being based on the work of two other writers. First came a short story titled “The Two Bad Hats” that Monckton Hoffe either wrote expressly for Paramount or else sold to the studio. Next came an adaptation of the Hoffe story by Jeanne Bartlett. Sometime in 1938, Lewin assigned Sturges to turn these materials into a screenplay. As Sturges usually did in such situations, he began by tossing out most of what he’d been given. All he kept was a high-toned British milieu (transformed in the finished film into mere imposture), a little intrigue involving card playing, and the outlines of a character: a beautiful young woman who fraudulently impersonates a nonexistent twin.

In the source material, the names used by this woman were Salome and Sheba, the first for the bad persona, the second for the good. This conceit of giving characters biblical names was something else that Sturges retained—but he changed his duplicitous woman into Jean/Eve and reinforced the associations of the latter name by giving the man who falls for her a professional interest in snakes. It remains to be seen what Sturges may have intended by these choices; but it’s certain that whatever was original in The Lady Eve, whatever gave Sturges the right to call this story his own, had its roots in the Garden of Eden.

That’s where The Lady Eve begins: in a tropical landscape that might indeed be Paradise, except for already having been tainted by lust, cash, and curiosity. Charles, with pith helmet and gun, is the agent of the latter two forces, having brought a scientific expedition “up the Amazon” with his father’s money. As for the lust, that’s evidently been the preoccupation of Charles’s protector and sidekick Muggsy (William Demarest), to judge from his gruff dockside farewell to a mute, expressionless native woman. She hangs a wreath of flowers around Muggsy’s neck— the chain of them big enough for a horse, their blossoms obscenely huge—while Charles, oblivious to this utterly emotionless sexual transaction, natters on to the research team about wishing he could live forever “in the company of men like yourselves, in the pursuit of knowledge.” He apparently hasn’t noticed anything impure in his version of Paradise; nor does he conside the implications of carrying a snake out of it, into a world where the men, and even more so the women, cannot possibly live up to his ideals.

The Lady Eve begins as the story of a man who not only believes he’s found Eden but thinks he can leave it and come back later. The Bible says it doesn’t work that way; and so Charles’s willingness to leave the jungle—temporarily, of course—provides the first hint that his path will diverge from Adam’s. By contrast, his failure to return to the jungle at the movie’s end suggests that The Lady Eve might in some way conform to scripture. A moviegoer who wants to think about this story as carefully as Sturges did will need to follow a narrative that runs parallel with the Bible and also on the bias to it.

If that moviegoer is familiar with Sturges’s other films, Charles’s failure to return to the jungle will mark him as diverging from another model as well: the Sturges protagonist who comes full circle.

You see this pattern in the Sturges movies that start at the story’s end (The Great McGinty, The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek), or at a beginning that looks like the end (Sullivan’s Travels, The Palm Beach Story), or on the occasion of a eulogy, when hindsight is at its most intense (The Power and the Glory, Triumph Over Pain). Despite the famously hectic pace of these films, despite the crowding of incident and stock players, their structures make it seem as if everything has already been decided in them; the audience just needs to discover how much bustle it will take, and how many surprises, to attain the foregone conclusion.

As with all good comedies, an undercurrent of disquiet runs through Sturges’s films—an anxiety, in his case, about being stuck in an eternal return. The failed Marine who is the protagonist in Hail the Conquering Hero struggles to escape from his hometown and the imperative to live up to his late father’s military fame but remains hopelessly trapped in both. Characters in Easy Living and Christmas in July go over mathematical calculations obsessively (if incorrectly), as if imprisoned by their logic. Events are recapitulated (Christmas in July, The Palm Beach Story), days are skipped and have to be revisited (The Sin of Harold Diddlebock), and characters conclude their adventures by resuming their old behavior (The Great McGinty).

Charles, too, might seem to fit this pattern. Tripped by a temptress at the beginning and end of The Lady Eve, he suffers the same fall in the same place, and the second time is restored by it to his keynote state of blessed ignorance. Now he and Jean are back where they ought to have started, prompting her to ask, in summation, “Why did we have to go through all this nonsense?” And yet, as one might hope from a comedy based on the story of Eden, the movie ends on a note of salvation. Charles has successfully broken the circle, or rather had it broken over him. Although he had thought he was going back to his false paradise on the Amazon, it’s obvious at the finale that he’s heading in an entirely different direction.

As Jean has done throughout the film, she concludes The Lady Eve by diverting Charles, in the full sense of the term.

Even before Jean has dropped the apple onto Charles’s head—playfully, just to see if she can—Sturges has suggested her power to move him any way she likes. These hints come in the second scene as a prelude to her introduction, as Charles and Muggsy in their chugging little Amazon boat approach the cruise ship that will take them aboard. Sturges makes a gag out of the encounter, showing the smokestack and whistle of one and then

the other vessel as they salute on the open sea. The puny whistle on Charles’s boat chokes and boils over impotently, straining to achieve a mere piping ejaculation. The whistle on the other boat returns a blast that could knock a man backward. Not that you know yet that Jean is associated with this bellow. Only after Sturges has reviewed the faces of the cruise ship passengers at the rail, as they gossip about Charles Pike’s wealth and marriageability, do a crane shot and a dissolve lift the camera to the deck above, where Jean and the Colonel are discovered standing in a position very superior to Charles, already plotting to cheat him.

At this introductory stage, the mistress of card games has not yet done much to show that she can toy with Charles; her abilities are merely implied, through the associative editing and construction of cinematic space. (These were Sturges’s contributions as the director. In the screenplay, he made little of the ships’ whistles and didn’t think of an upper deck.) In the next scene, though, Jean asserts herself, demonstrating an almost magical command over Charles, her immediate surroundings, and possibly the movie itself.

In the main dining salon of the SS Southern Queen Charles sits alone, reading a book titled Are Snakes Necessary? while every eligible woman in the room strains to catch his eye. Jean, however, does not strain, nor will she stoop to compete. Instead, she amuses herself, studying everyone surreptitiously with the aid of her compact mirror. As many writers have noted, the image in the mirror creates a frame within the frame—in effect, a secondary movie. The events that play out in it provide Jean with the material for a self-delighted satirical commentary, in which she voices the unspoken thoughts of the people she’s watching, supplies lines of their unheard dialogue, mockingly advises them on the attitudes and actions they’re adopting, and even predicts what they’ll do next. In her omniscience, she might as well be a writer-director creating a film.

I would go so far as to say that the film in question is a Preston Sturges movie, since the combination of her running remarks with more-or-less silent images replicates the widely touted method of “narratage” that Sturges had claimed as the great innovation of The Power and the Glory. As a writer who was then only beginning to make his way in an industry that gave directors precedence, Sturges may be said to have invented narratage to serve as both a tool and a weapon; it gave his words equality with the director’s images, and even dominance over them. Although Hollywood failed to recognize the potential of this modern breakthrough and sent him back to contract work, he reintroduced narratage for Jean, who is unmistakably tickled by the powers it gives her.

She also knows the limits of these powers—perhaps better than Sturges did, to judge from a memo to himself that he inserted into the final script. Just before a passage of Jean’s commentary, he wrote: “Only enough of this dialogue will be used to match the action.”

His plan, evidently, was to shoot the images first and then record the words, trimming and adjusting them so the timing would come out right. This would have been the sensible way to proceed, or at least to explain his intentions to the supervising producer; but in the finished film, the entire block of words remains intact, suggesting that the images were instead timed painstakingly to the dialogue. Sturges the screenwriter had won out, at the cost of some trouble to Sturges the director.

Jean, however, shows she prefers action to words. Having thoroughly enjoyed her seeming ability to control people and events through her language, and having had a good laugh at the contrivances of every other woman in the dining room, she triumphs at the end of the scene by deploying a direct, physical tactic that none of the rest had considered: she sticks out her foot and trips Charles.

Then she stands and speaks for the first time to the abashed and disheveled prey she’s brought down. At this moment, as James Harvey notes in Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, familiar points of reference snap into place for the audience. Jean abruptly takes on the well-established aspect of a Barbara Stanwyck character, while the banter shifts into the known, reassuring channels of screwball comedy. Harvey’s comment is astute; but it’s worth remarking that the moment is not only funny but also stunning because of the violence with which Jean wills herself into the action. Like an actress who hurls herself out of the wings and onto the stage, she has just committed herself in the flesh.

For the remainder of the first half of The Lady Eve, she will rely less on her words than on her body, and on the physical skills (not least of them sleight of hand) that are ingrained in it. She won’t return to her verbal wiles until the film’s second part, when she transforms herself into Eve. For now, the flesh comes first, while her use of language proves to be remarkably honest, even if her purposes are not.

She is a con artist who gives fair warning. She joins Harry in directing Charles’s attention to a sign in the lounge advising passengers to beware of professional gamblers and informs him that Harry is a good card player. At the end of her first game with Charles, when she and Harry have baited their victim by allowing him to win, she all but announces the swindle (“How much do I owe the sucker?” she asks across the table), assures Charles that she will get her money back, and promises that, if losing will salve his conscience, he will soon feel a lot better.

Even more important, she speaks honestly about the power of her body and how she uses it. Early on, Jean patiently explains to Charles that she’s flirting with him (he’s been too dazed to understand). In the most candid question ever whizzed past the enforcers of the Production Code, she asks him, eye to eye and nose to nose, “Don’t you think we ought to go to bed?” (All she means is that it’s too late at night to go dancing.) Later, she advises Charles that it’s dangerous to trust people he doesn’t know well, or to plunge into a shipboard romance. At a critical point in her relationship with him—very soon after he’s learned that she’s a crook, but immediately before he reveals that he knows—she even recalls the wiles she’d used to get him sexually worked up and confesses, from the heart, that she hadn’t expected to fall for him.

By the time Jean gets to this point, her words and her body are saying the same thing and meaning it. There is no distance between them—nor is there any distance in this revelation scene between Sturges’s words and images. The rest of his movie will depend on the audience’s believing that the deceitful woman is speaking plainly, that the powerful woman can be hurt and is owning up to her weakness. So after Jean’s secret has been laid bare, Sturges cuts from a wider view that shows some of the surroundings to a close two-shot that admits into it nothing except the characters and their emotions. He positions the actors so that the focus is on Jean, who faces the camera, with Charles in profile, a little bit out of the light, on the right side of the frame. Under this scrutiny, Jean begins to weep. (The script merely called for her to bite her lip before exiting—but Sturges, as director, understood the resources he had won for The Lady Eve by securing Stanwyck, who specialized in tears.) Most important of all, Sturges the director ordains that Charles will refuse to look at Jean. If he would only turn his head, he would recognize at once what the audience understands, that she’s pouring herself out to him. But the image now confirms what the plot and dialogue had been telling us: Charles literally cannot see when someone is telling him the truth.

Earlier, Jean’s truth-telling had been an amusement, for her and the audience; she could indulge in it safely, knowing that Charles wouldn’t believe the plain meaning of her words. Now her truth-telling is desperate; she needs him to believe her words, and he’s incapable of it. Her remedy, in the second half of the film, will be to give him the deception he deserves. She will take on a biblical name—Eve—and put on an imposture in which almost every word that comes out of her mouth will be a lie, even in its British pronunciation. In this guise, Jean will be much more like the temptress of traditional scriptural interpretation, a figure so closely associated with the Father of Lies that you can’t tell, looking at the pictures by Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder and Titian, whether Eve is receiving the fruit from the serpent or feeding it to him. In Blake’s picture, where Satan coils around her, it’s even difficult to see where her body ends and the serpent’s begins.

*