Like musicians, writers can be formally schooled or self-taught. Very unlike neurosurgeons, for example. Here’s a question for a later day: If self teaching is possible, why bother with all the expense, competition, petty rivalries, etc. that accompany formal instruction?

I myself am in the self-taught category, but from a sub-category within, namely those who were helped along the way by a family member. Think of Stevie Ray Vaughan, who started playing the guitar at the age of seven, under the tutelage of his older brother Jimmie. My Jimmie Vaughan was my mother, Enid Abrahams.

The first book I read to myself was The Four Bad Hens at age six, but I soon discovered what I really loved to read, which were mysteries and adventure stories. Especially adventure stories, such as Treasure Island. One of my very favorites was Red Pete the Ruthless. I still remember the last scene, with Red Pete buried up to the neck between the high and low tide lines, surrounded by his stolen gold, waves lapping closer. Does it get any better than that? I may rework—okay, steal—it one day for purposes of my own.

I was very lucky to be in a class from fifth through eighth grades where we had to write some sort of piece—essay, poem, short story—every week. I always wrote a tale of high adventure. Of all those reams of derring-do, all I remember is one first sentence: “The archaic telephone jangled shrilly in the murky tropical night.” Then came four or five convoluted and illegible pages of drama in the Amazon jungle. My mom would read it over. (At that time she was starting out in a promising career writing television plays and was making inroads into Hollywood—all interrupted when she was felled by cancer, dying quite young.)

Mom’s method was Socratic. She’d point to that first sentence. “Is ‘archaic’ the exact right word here?” No. Just agonizingly close. She wouldn’t give me the answer (“antiquated”). I’d have to find it by myself. Then she’d say, “Doesn’t ‘jangled’ take care of ‘shrilly?’” Yes, Mom. “So do we need ‘shrilly?’” Nope. And to this day, you’ll find very few adverbs in my work. Adverbs, weak; verbs strong. Plus you see here another feature she was big on: having one word do the work of two, or three, or four, one sentence do the work of a paragraph, and by extension phrases that handle character development as well as plot, theme as well as mood. The explanatory detail the reader needs in order to understand the story is almost invisible, folded in like truffles in a cream sauce. She left “murky, tropical night” alone. Juvenile, but it does the job.

Mom wrote wonderful dialogue—behind the beat, ahead of the beat, then boom-boom, right on. Dialogue is such a powerful tool. No two people speak the same, and in a really good passage of dialogue you don’t even need “Johnny said,” and “said Gina.” And almost goes without mentioning, Mom hated all those tortuous substitute words for “said”—no “Johnny breathed,” or “Gina harrumphed.” Mom was also strongly opposed to prepositions and prepositional phrases. “Nevertheless,” “however,” “to be sure.” Sentences, she said, should connect through the force of ideas connecting. If you find yourself using a lot of prepositions, go back and check your ideas. (Aside: newspaper articles are full of prepositions these days.)

I’ve summarized what Mom taught me in the following list of Laws. I guarantee these laws are more helpful than many now on the books.

___________________________________

Enid’s Laws

(circa 1957; annotations and #7 are mine)

___________________________________

1. Organization is everything.

If the story isn’t organized, what have you got? A mess. To be organized, you must make some big decisions from the get-go, such as: What’s the POV? One character? Multi? Tell it in first person? Third? How about the tense? Tone? I’ve got a nice beginning but will it lead to an end? Getting stuck without an end is bad. Make sure an ending is possible, and “the world blows up” doesn’t count. There are maybe 10,000 decisions in writing a novel. Accept that.

2. Fiction is about reversals.

Just like high school or college wrestling (meaning real wrestling). It’s much more fun to watch a back-and-forth match than a blowout.

3. Torment your protagonist.

Or, flipping it the other way, don’t fall in love with your characters. And the main character—perhaps hero, perhaps not—needs to be tested.

4. Push everything as far as you can without contriving.

Get everything you can from your ideas—don’t leave the gold mine only partly dug. But stop before you do anything that makes the reader feel your behind-the-scenes presence and think that terrible thought: That couldn’t happen. Warning: pushing things as far as you can can end up pushing you, the writer, out of your comfort zone and into new territory. Worth the risk? You be the judge.

5. Always advance the story.

Sometimes when you’re writing you’ll come up with a lovely little passage, a description of sagebrush at sunset, say, and a white dove gliding low. Does it move the story forward? No? Then out it goes. Shoot that dove!

6. Be original.

On every page! In every paragraph! No boilerplate! Ever!

7. Be playful.

You can be playful and dark in the same story. (Look around you.)

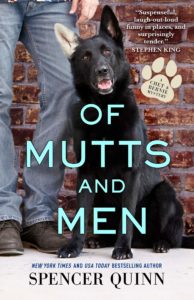

And here’s a writer’s block bonus for readers at CrimeReads: If you get stuck, take a step back and remember the engine that’s driving your story, its spirit, its heartbeat. Some narrative way forward will always suggest itself. (Please ignore this advice if your story is engineless.) In the case of the Chet and Bernie novels, the engine driving the story is the love between Chet and Bernie.

***