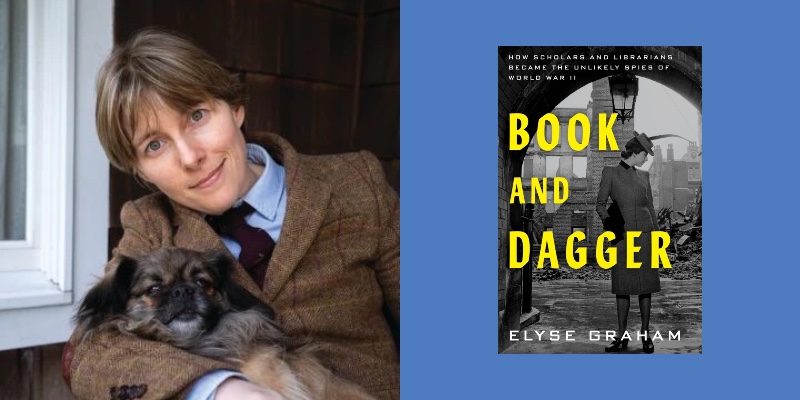

As Elyse Graham recounts in her new book Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II, with the Nazis gaining ground across Europe in the early years of the Second World War, the United States and United Kingdom drew on an unlikely reserve of combatants to build new spy organizations from the ground up. Instead of employing suave lady-killers or gadget whizzes, they turned to a group of people whose skills and areas of expertise would not only alter the fate of World War II but of modern spycraft for decades to come: academics and librarians.

In our interview, Graham told me she had “a lot of fun” researching Book and Dagger, and that delight shows on the page: her book is full of stories of unlikely characters who became crucial spies for the Allied forces (like Joseph Curtiss, a shy Yale professor who wound up temporarily running America’s espionage bureau in Istanbul), how-to tips for making it as a spy in the 1940s, and perilous tales of industrial sabotage. While the men and women who undertook these undercover operations were undeniably heroic, their profiles were much different than the figures we see in spy movies, and they were backed up by bureaus of researchers at home who made essential discoveries based on their research.

As Graham explains, Book and Dagger not only showcases the power of libraries and the humanities — two institutions currently under threat from right-wing campaigners — but also reveals what ordinary people can do to fight authoritarian regimes. “The reserves of courage that ordinary people found to win against the Reich impressed me the entire time that that I was writing this book,” she says. “The fact that they really did make a difference taught me something also about the power of power from below.”

Morgan Leigh Davies

I want to ask how you got interested in the subject. Do you have a passion for the period, or for spy novels? How did you come to write this book?

Elyse Graham

I write a lot about the history of universities, and I became curious about why, during a certain period of the 1950s and 1960s, all of the spies going into the CIA from places like Princeton and Yale were getting recruited from English and history departments. It turned out that figuratively, and maybe literally, all of their professors had been spies during World War Two, which was a very exciting story.

And of course, anybody in academia is familiar with secret keeping and grudges and all of the sleuthing and gumshoe work that you have to do to get your hands on highly prized papers, which is exactly, it turns out, the set of talents that these spies were prized for during their time fighting the Nazis. From there, it’s a true story with the plot of a spy thriller.

MLD

It was really interesting to see the overlap between the skill sets required for so many of these different fields that were applicable to this spy world. How much did your background as an academic give you insight into the sort of work that these people were doing?

EG

Spending time in archives, you learn a lot, not just about the tremendous amount of information that’s available, but also all of the things you have to do to get access to information that exists, but it’s not immediately obvious that it exists. So it takes time, for example, for a library or an archive to put stuff on the catalog. It can take decades. So sometimes you know that something exists but you have to go through back channels to get access to this thing that isn’t on the catalog yet, and that you wouldn’t know existed if you were simply going by the catalog. There are tricks that people tell each other about how to make use of certain archives. Traditionally, women have told each other, while making use of the Vatican archive, that you get a better response if you take off your wedding ring. So these are very human histories.

This story has a lot to teach us about today’s world in a sense, not just that these ways of finding out information are still used, not only by intelligence agencies, but also by professors and other people who want to pull stories out of the past and unearth hidden histories. It also teaches us about the value of libraries, not just as centers of community and education, but as places that preserve information. Information that you don’t even know is going to be valuable until all of a sudden, it helps you to plan the invasion of North Africa. The value of the readers that those libraries nurture, people who learn how to read in all sorts of different ways that turn out, again, to be incredibly useful.

MLD

One of the things that really struck me is how much information they were making use of that was publicly available. Of course, there’s a huge amount of effort that has to go into digging that stuff up and putting it together in a coherent package that makes it worthwhile. But that struck me as kind of counterintuitive to the spy narrative that we have in our head, which is not necessarily based in reality in any way, right?

EG

The activity of these spies in the field, and these intelligence analysts who are making use of the documents they sent home, reshaped all of spycraft. It was really the growth of intelligence analysis, which is the basis of how the CIA works today. The spymasters at the OSS [Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA] had an idea, which is that 90 to 95% of the information that you need in order to, for example, find out about someone’s military capabilities in order to fight a World War, is publicly available. It’s in newspapers, in unlikely places like the society pages of a local newspaper, in color details in somebody’s travelogue about a trip to Greece. These are old fashioned references today, but people actually do get very actionable military intelligence by looking at people’s Instagram posts.

You could look at what were known as Aunt Minnie pictures, which is just a photograph of somebody’s Aunt Minnie standing outside of a building, or at a phone book for a certain city, or you could read every single part of the newspaper as ingeniously as you possibly could. That gets you 95% of the way there. It was a fairly new idea in intelligence. Before then, a lot of intelligence had been conducted by way of whisper networks around embassies. What do diplomats know? What can people tell us by actually doing it the way that it was done in spy novels, which is to eavesdrop on people in a smoke-filled lounge. This was different, and it had a romance, but it is the romance of books and libraries.

MLD

The kinds of information and material you’re describing feel to me like types of information that women would be more suited to understanding or picking up on, especially at that time. How much did gender played into this process?

EG

In movies, spies are often these ripped hunks who are carrying a lot of gadgets. They’re wearing tuxedos and they’re sleeping with their sources. But that’s not how it works in real life. In real life, a weapon would blow somebody’s cover. A gadget would blow somebody’s cover. If the Gestapo stops you and you have a shoe that turns into a telegraph machine, you are a spy, you don’t have a cover anymore.

So first of all, spies were chosen precisely because they would be overlooked. Hence the value of women as spies, which was really discovered during World War Two. There was a guy in Britain, Selwyn Jepson, who recruited women because he thought that they were much better spies than men. Most informants don’t know they’re informants. If you’re trying to get information out of somebody, you don’t want to be the person who asks a bunch of questions that will get you noticed. But if you say something incorrect, especially if you’re a woman, a guy’s going to come in and explain things to you. This was explicitly a part of the training wherein they were told, just say something that’s a little bit wrong, and guys will come in and they will explain things to you, and they’ll be sources. They’ll have no idea that they’re sources. They won’t remember your face. They may remember your legs.

Women would be chosen precisely because they would be overlooked, and also sometimes because they would blend into the background in cities in which all of the men had been forcibly recruited to fight for the Germans: women were the only ones left behind.

MLD

When World War Two started, spy agencies weren’t particularly robust in the UK or the US, so these people were modeling their behavior in some way on fiction. How did that influence them as the war went on?

EG

The great history of Robert Darnton says, literature doesn’t just reflect upon history. Literature creates history. So we model our own lives after the things we read. When the US went into the war, they had to create a spy agency out of nothing, which meant that the people who were running the training camps had read novels about spies, and that’s about it. So they used techniques ripped out of spy novels at first while they were figuring out what to do. One of the characters in the book, Joseph Curtiss, was told, “Go to this train station, and you’ll see a man wearing a red carnation,” where he was told, “Wear a purple tie. Go to the Yale club. You’ll see a man smoking a cigarette who will put it out on the table.” That’s just from a spy novel.

On the one hand, this sort of thing can give people a lot of courage at a time that they need courage. So there’s a young man, Varian Fry, who had seen a lot of movies. I mean, he was educated, but he went undercover in France and just acted like Humphrey Bogart the entire time. His job was to try and rescue people who were being targeted by the Gestapo, and he would give them, like in Casablanca, visas, letters of transit that would allow them to escape to the United States. He had no idea what he was doing, but he just acted like Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney mixed together. And it worked. That’s the American way. You know, you can go in there, and have seen a bunch of Hollywood movies, and just do it with this kind of reckless optimism and goodwill. That’s a possibility for you, if you’re an American.

I was very entertained also, while I was researching, by how thoroughly the fact that these guys had read spy books both informed the things that they chose to do and also taught them about their own mistakes. The people who turned out to be the worst spies were the ones who would not let go of the idea that they were in a spy novel. They had to be the center of the story. Every time they walked into a casino, the band would strike up the song, “Boo Boo Baby I’m a Spy.” They would dance, they would sing. It’s all very entertaining. It can be dangerous to be so insistent on putting yourself at the center of the story. There has to be a certain ability to let somebody else take all of the attention, which, again, is something that women have been trained to do a little bit better than men.

One of the things that I learned while writing the book is that what you have is what you bring to the war. To a certain extent, when your back is against the wall, you fall back on your training. So the English went into this like English people: they had spy training schools that were incredibly posh, that were in these country manors and had house masters and servants and that sort of thing, because they were English. That’s what they knew. So that’s what they fell back on. The Americans had these camps with tents where they were teaching people how to do quick draws like cowboys. Now, again, if you are a spy, you don’t get a gun. But they were still teaching them how to do quick draws, because they were Americans. So of course, they trained like cowboys. The Norwegians were out there on skis, the French Resistance robbed liquor stores, drank the wine, and then turned the empty wine bottles into Molotov cocktails. Because they’re French, they do as the French do.

My point here being that the librarians also fell back on their training, and it turned out to be unexpectedly exactly what modern intelligence needed, if you think about the world of libraries as kind of its own nation. These guys fought in their own characteristic way, and it turned out to be so successful that they were hugely instrumental in winning World War Two and created the basis of modern spycraft, which is very impressive. And of course, they also had red spy novels and thought it was kind of fun that they were spies themselves. The better ones learned that you can’t always act like you’re in a spy novel. The worst ones didn’t learn that. But there’s this constant back and forth between fiction and real life.

MLD

There are a couple instances in the book where the American or Allied spies really managed to manipulate the Nazis because they used that academic cachet. There’s an idea that, because you’re from an educated background, that you’re above it all, which obviously the academics who go into spying for the US mostly don’t have, because they’re willing to go risk their lives to do this.

EG

One aspect of the academic world, especially in the 1940s, is prestige. You know, the three-button wool suits, the air of being a certain kind of gentleman — even into the 1960s and 1970s, “gentlemen” is a word that’s frequently used by professors at Ivy League schools, rather than referring to students. It is also the case in in Nazi Europe that some of the people who take charge see themselves as gentlemen, as men from a better world who are suited to rule. When these guys were caught and interrogated by the Allies, they thought, “Oh, the people who are interrogating me are from Harvard,” which is the case for a specific group of men in the book who are interrogating Nazis at what was called House 71. “These are gentlemen. I am a gentleman. Naturally, they would send Harvard men to talk to me, because I am worthy of being interviewed by a Harvard man. I’m not going to get in any trouble because we’re all gentlemen. Here, I’m going to tell them everything.” Some of them turned themselves in to the Monuments Men and the Art Looting Investigation Unit, which were the Allied units in charge of getting back stolen art before the Nazis could sell it or melt it down for bullets. They turned themselves in because they thought that they would simply be working for a new employer.

Now, the fact that they weren’t simply working for a new employer, that they were caught and interrogated and punished, is largely because the scholars decided not to follow the orders of the US government, which was considering for a time actually taking the art as part of the spoils of war, which would be traditional. But these were historians, real art historians, who really valued the art and not just themselves. And they said, Hey, let’s not do that, which was the start of a new way of doing things.

I was very struck by the conversations between, on the one hand, the Nazis in House 71 and on the other hand, the Americans who had to wear themselves as a disguise. The prestige, the pomp — they played into it, because it’s what the Nazis wanted. One of them, James Plaut, happens to be Jewish, but he was a Harvard man, and he understood the gestures of assimilation. He understood the art of disguise and the Nazis did not know that he was Jewish. They just knew that he was a Harvard man. So he got them dead to rights, which must have felt very satisfying.

MLD

I was moved by the fact that those academics actually believed in their profession and said, No, we can’t.

EG

The spies on the ground, the spies in the book, are also making very real moral decisions. Would you sink a ferry filled with civilians if you knew that it would deny the Germans access to something that might enable them to create a very powerful weapon without knowing what heavy water is, without knowing what a nuclear bomb is? Would you sink a ferry full of civilians if you were told the war might depend on it? What if, also a situation in the book, your friend was scheduled to be on the ferry? What if your mother was scheduled to be on the ferry — also a situation in the book. If you warn them, the word might get out and the Nazis might get the substance. Would you follow the orders of your government and do what has traditionally been done, which is to take art that has been acquired in war home to pay for the war as the spoils of war? Because you, yourself, are an art historian, it could make you very famous. Imagine that you could take some Vermeers for yourself, put them in your university’s library, study them, become a world-famous Vermeer person. That must be very tempting.

You’re guarding a warehouse full of art after the war. Much of their art was painted by Nazis themselves, not particularly good art, but painted by people like Julius Stryker, and his watercolors are with you, and you don’t have a lot of space. Should you burn his paintings? Give yourself a little more space, indulge in a little revenge at the same time: it would be very satisfying. I actually talked with historians and art historians about whether they would do this, and I won’t name names, but one very eminent person said that they would, and another very eminent person said that they wouldn’t. Personally, I would, but that’s why I’m not tasked with these kinds of decisions.

You were on the ground, you weren’t connected to anybody else. You had to make these very large decisions, kind of on your own, on the basis of the training that you had been given. As it happens, these guys had training from being art historians. They had been taught certain things about the love of art that guided the decisions that they made in a time before and its aftermath. So nothing that we learn is useless. It all comes to bear sooner or later.