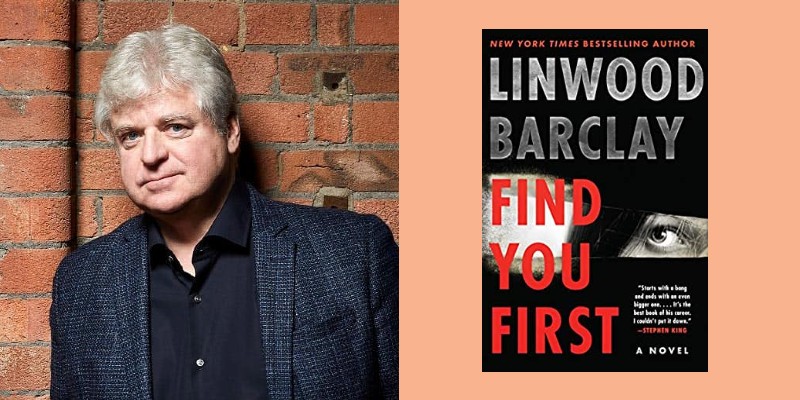

Linwood Barclay is the author of eighteen novels, and two thrillers for children. A New York Times bestselling author, his books have been translated into more than two dozen languages. His latest novel, Find You First, about the mysterious deaths of a tech millionaire’s would-be heirs, is now available.

___________________________________

Otto Penzler: This is your twentieth adult novel. (With a pair of Young Adult ones to your credit, as well.) However, your first fiction—the four books featuring amateur sleuth Zack Walker, starting in 2004—were quickly overshadowed in 2007 by the immense success of the thriller No Time for Goodbye. It seems you haven’t looked back since then. But was becoming a writer always a goal? And had you ever imagined a full-time career as one?

Linwood Barclay: I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was 11 or 12 years old, and by my mid-teens I was sure I wanted to write TV scripts. I was obsessed with shows like Mannix, Mission: Impossible, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., and Columbo, and wrote what today we would call fan fiction. An episode a week was not enough to satisfy me, so I had to create my own adventures. I asked my dad to give me a lesson on our Royal typewriter that was about as heavy as a Volkswagen. I have very little memory of anyone actually reading my TV-inspired works, but that was okay. I wrote them for me. Not surprisingly, there was not a big demand for TV writers where I grew up in rural Ontario. My local high school had a careers binder bigger than the New York phone book, but nowhere in it could you find “screenwriter” or “novelist” or “TV writer.” Dairy farmer, yes.

OP: Of course, always before writing, there’s reading. Here’s a question I realize you’re often asked; still, not everyone reading this will be able to anticipate your answers. To wit: who are a few of the authors you feel were most influential to your work? And who have you most enjoyed reading?

LB: As a young kid, I devoured the Hardy Boys, then moved on to Agatha Christie and Rex Stout, with plenty of Ray Bradbury along the way. But it was Ross Macdonald (Kenneth Millar in real life), more than anyone, who left his stamp on me, creatively and personally.

When I was 15 I picked his Bantam paperback edition of The Goodbye Look off the twirling, incredibly squeaky, paperback rack in my local grocery store. And then I had to read everything by him. He was the writer who showed you could use the conventions of the detective novel to tackle big issues. Family dysfunction, environmentalism, disaffected youth.

In university I wrote to Millar care of his publisher, looking for critiques of his work that would help with a thesis I was writing, and then, in a subsequent letter, I asked if I could send him a copy of a novel I had written. (I realize now what a terrible imposition this was.) But he said sure, and that was the beginning of a long correspondence between us, culminating, when I was 21, in a dinner together when he and his mystery writer wife, Margaret Millar, came for a visit to Canada.

In my hardcover edition of Sleeping Beauty, he wrote: “For Linwood who will, I hope, someday outwrite me.”

OP: Despite my many decades in the book business, I remain curious about each writer’s path to publication. It can occur in so many ways. I know you began by working on newspapers, and I’d like to hear your version of how it unfolded from that point on.

LB: By my late teens and early twenties, I was writing novels based on my own characters, instead of the fan fiction I mentioned earlier. I mailed them off to all the major publishers in New York and Toronto. Many of them were able to reject my offerings before I even got home from the post office. I think we can all be grateful these books were not published.

So, at the age of 22, I thought, if I can’t be published as a novelist, where can I get paid money to write every day? The answer was: newspapers. I got a reporting job at a small Ontario daily, The Peterborough Examiner, where I covered such fast-breaking stories like the guy who made interesting crafts out of walnuts, and a disease that struck cows called brucellosis. I wrote so much about that ailment I was convinced I had the disease. I had the number one symptom: I could not produce milk.

A few years later I landed at Canada’s largest circulation paper, The Toronto Star, but was taken on as a copy editor. They had all the reporters they needed. (City editor: Do you have lots of copy editing experience? Me: Uh … sure.) I turned out to be good at editing, and held many senior editing jobs until, 11 years after joining The Star, I got a gig as a humour columnist. Now I was writing again, all the time, and this led me back to my original dream of writing books. I did four humour books (one a memoir) for the Canadian market, but in 2004 I managed to get back to the original dream, of writing crime novels. My agent sold my comic thriller, Bad Move, to Bantam. It featured a character named Zack Walker, and three more novels starring him would follow.

But these thrillers were not big sellers. My agent suggested a change of course. A dark standalone. I came up with an idea about a young girl who wakes up one morning to an empty house, and 25 years go by without ever knowing what happened to her family. The idea came to me at 5 a.m., and it changed my life. In addition to the U.S., we sold it in Germany, where it was an instant bestseller, and to the U.K. where it finished out 2008 as the top-selling novel of the year (thanks to being a pick from the Richard & Judy Book Club).

I was set. That book’s global success allowed me to leave the newspaper (all the previous novels had been written while still cranking out about 120 columns a year) and devote myself to writing a book a year. My teenage dream had finally come true.

OP: When you launch yourself on a new book, is the idea for it always fully worked out? Or are you ever surprised to find that the story has started taking on a life of its own?

LB: Before I start writing I want to know where I’m going to end up. It’s like you leave New York, knowing you’re going to drive to Chicago, but there are any number of routes you can take to get there. I know the big picture, who did what and to whom and why, but I don’t know the opportunities that exist in the novel until I get into it. There are detours, side-trips. But I always get back onto the interstate at some point.

OP: Genetic science is important to the plot of Find You First. Is research a significant part of each of your books as it gets underway? Or before you even settle on the plot?

LB: I do whatever research I need to do to tell the story, but I don’t immerse myself in it the way many other writers do. Find You First doesn’t delve into the details of how DNA testing is conducted. It is enough for me to know that it can be done, and the kinds of situations it can lead to. I’m more interested in people, their emotional reactions, the secrets they want to hide.

OP: You’ve had two different series characters: Zack Walker in the four earliest books and Detective Barry Duckworth in the Promise Falls trilogy (Broken Promise, Far from True and The Twenty-Three). Are these characters you find yourself identifying with, or are others even closer, as in the present book, for example?

LB: I definitely identified with Zack Walker. I mean, he was a complete pain in the ass. I hate to tell you how closely he’s based on me. Zack is me unchecked. I am riddled with anxiety just like him, and while I might think of responding the way Zack does, I wouldn’t. But Zack can’t stop himself. Case in point: Zack might “steal” his wife’s purse from the shopping cart to teach her a lesson about making it available to thieves, but I would only imagine doing it. I wouldn’t do such a thing, because I want to live.

OP: Your work has been identified as “psychological suspense.” We certainly hear the term frequently in the crime and mystery genre. Is there another way you’d choose to characterize your books?

LB: Fun.

OP: Find You First offers a growing array of characters as it progresses. Is part of the enjoyment you derive from your immersion in each book the creation of these figures as you work to bring each to life to play their role?

LB: This book does have a large cast of characters, although some only appear for a short time before something very bad happens to them. I think the enjoyment comes from finding a way to make all these characters’ stories come together, as seamlessly as possible. How can some kid in Indiana have anything to do with some rich, evil, megalomaniac in Manhattan? What does some college student in Maine have to do with a wealthy tech entrepreneur in New Haven? It’s great fun to slowly reveal all the connections.

William Goldman’s Marathon Man was a massive influence on me when I read it in my late teens. Those early chapters appeared to have nothing to do with one another. But when these various strands started to come together, what fun.

OP: Aside from the authors who most influenced you, and those you’ve most enjoyed, which writers today do you find yourself most eager to read?

LB: There are so many, I’m hesitant to make a list for fear of leaving someone out. But who do I buy in hardcover as soon as they come out? James Lee Burke, Stephen King, Robert Crais. Steph Cha is someone to watch (her Your House will Pay was stellar). Mary Roach, the only science writer I read because she’s so hilarious. Richard Russo. Okay, this is getting out of hand. I have about twenty more. And I want to mention that I was late to discovering the late Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels, and during the pandemic read them all. What a body of work.

OP: Let’s end with a familiar query: What advice would you offer those writers who are just starting out, right now, in 2021?

LB: Read. This simple bit of advice is as solid now as it was ten or twenty or thirty years ago. If you’re going to be a writer, you have to be a reader. There is no better way to learn. You wouldn’t aspire to be a director without watching movies, or a chef without loving to eat. And if you believe you would like to be a writer, you are already writing, even if it’s only for your own enjoyment. You’re doing it because you can’t not do it.

So, you’re reading, you’re writing, and you’ve written a book. What now? I don’t know much about self-publishing, so I’ll speak to a more traditional route. Find books like yours, scour the acknowledgments for the names of agents. Query them. A very short letter. A line about yourself, a couple of sentences about your book. Don’t say it’s the next Gone Girl or I Am Pilgrim. Attach chapter one.

Agents are busy people, but plenty of them will at least read the first couple of pages. You’ll live or die based on those. I believe the best way to get their attention is with tone, a distinctive voice. Maybe Elmore Leonard said it best: “Don’t start with weather.”

And if you don’t hear back about your proposal, don’t feel badly. Agents are not in the advice business. They’re in the book business. Keep trying.

I wrote my first novels in late teens and early twenties. My first novel came out when I was 49. Don’t. Give. Up.