“London”

You only have to say the word, and like a powerful spell, an entire world is instantly conjured.

If you happen to have visited, you’re probably picturing red buses, Big Ben, Buckingham Palace and those guards with the funny hats. You may be picturing all those things anyway, even if you’ve never set foot in London just because you’ve seen it a million times on TV and in movies and so it all seems so familiar. Or maybe the spell conjures a different London for you, a city of fog and shadows, where horse drawn hansom cabs clip through crooked streets and men in top hats and capes make their way beneath the flickering glow of gaslights, the tips of their silver-topped canes tapping along the flagstones in time with their footsteps as hollow-eyed children watch them pass by.

If this is the London you picture then there’s only one man to blame – Charles John Huffam Dickens.

London is to Dickens as LA is to Raymond Chandler, New Orleans is to James Lee Burke, and New York was to Woody Allen before he became more synonymous with other, less laudable things. Each artist helped define the place they loved by writing about it and then, in turn, ultimately became defined by the thing they had written about. And though Dickens was writing over a hundred and fifty years ago, any modern writer who chooses to set a story in London automatically has the ghost of Dickens hovering over him. I know this to be true because I’ve just written one.

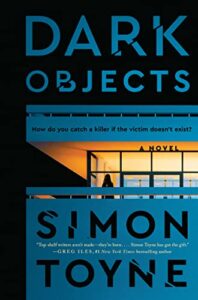

DARK OBJECTS, a contemporary crime thriller set in modern London, is, on the surface, about as far from both the London of Dickens and the books he set there as it’s possible to get. But, just as the bones of Dickens’ London are still visible beneath the flesh of the modern city as you walk through Chancery, or down Fleet Street, or through Covent Garden, or any of the stone lined lanes of the old city, so the shadow of Dickens falls across the work of any writer who dares to tread where he once trod.

To take an example, in my book I wanted to show how one crime can affect everyone in the city, from the lowliest, homeless person on the street to the very height of government and everyone in between. Pretty ambitious, I thought. Something you could only really do in the modern age, with a modern book, and with social media and the internet able to spread news of a crime like wildfire. Then I realized Dickens had already done it 170 years ago when he wrote ‘Bleak House’. Obviously, there was no social media in those days, though I bet if there had been Dickens would have live streamed his 20-mile daily walks into the seamier sides of London where he would gather material to later spin into his stories. Nevertheless, his incandescent passage at the death of Jo the crossing sweeper did in a few sentences what I was attempting to do in an entire novel:

“Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, right reverends and wrong reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us every day.”

Still, I figured, if I was going to abandon a project just because someone else had done something similar before I might as well put down my pen forever—even if that person did happen to be one of the greatest geniuses of English Literature.

Usually when embarking on a new book I pick a place I’d like to set it, then I go on a trip there under the vague but useful banner of ‘research’. Through this method I have walked through places as varied as the Arizona desert, the vineyards of Southern France, aircraft graveyards, pre-Roman ruins, and jungles accessible only by river. But when I set out to write “Dark Objects” it was during the first lock-down and no-one was going anywhere, so I had to do what writers and other fabulists have done for time immemorial. I had to dig into the archives of my own memories and experience and write about a place I’d already been.

Having lived and worked in London for all of my twenties and half of my thirties it was the obvious choice. And like anyone who lives in a city rather than simply visiting it, the London I know is a local’s London, a city far removed from the face it presents to visitors, a place of incredible variety, both good and bad, from jaw-dropping splendour, majesty, and history, to grinding poverty and deprivation, often co-existing right next to each other.

I dredged my memories and went back in my mind to the house I’d lived in, number 9, Zoffany Street in Archway, North London. Zoffany Street is alphabetically the last street name in London and number 9 is the last house on the street so naturally, when I lived there, I would say to people that I lived in the last house in London. I thought this might be an interesting enough starting point for a book, but in the end, it was a different house from that time that edged centre stage and became the focus of my story, an ultra-modern house of glass and steel, perched on the edge of London’s most exclusive and famous cemeteries.

I’d first come across the house on a walk—again summoning echoes of Dickens and his own London walks. My walks, unlike Dickens’s however, were not 20 mile marches but gentle strolls with a buggy up Highgate Hill with my new-born daughter to enjoy the leafier streets of well-to-do Highgate. Highgate, by dint of its elevated position, has always been a desirable place to live. In Victorian times it was even more desirable as it was high enough above the smog and stench from all the factories of Industrial England to make the air actually breathable. If the factory workers lived where I did at the bottom of the hill in the bowl of London, it was the factory owners who lived in Highgate.

You can see it in the architecture, the socking great houses, and the colourful and glamorous history that spans centuries. Coleridge lived in Highgate as he tried to kick his opium habit and Kate Moss had bought the same house in the early 2000’s. And if the houses weren’t impressive enough, the cemetery certainly was. It was where all those rich Victorians ended up, buried in mausoleums every bit as opulent as the houses they’d lived in. Anyone who was anybody was—and still is—buried in Highgate Cemetery: Karl Marx, George Eliot, Malcolm McLaren, George Michael, the actress Jean Simmons the actress (not Gene Simmons from Kiss as is sometimes been reported, who, at the time of writing, is still very much alive). And right on the edge of this cemetery, actually not even on the edge, right in amongst the gravestones, is a house so striking and modern and odd that it almost looks like a spaceship has landed in among the marble tombs and overgrown trees. If you want to see it then click on this freaky graveyard house link and you can read the same article I found when I was researching the book.

It was a house so peculiar and particular that I kept thinking about it. Why was it there? Who lived there? What did they get up to? And in the end, like the genesis of any story idea, it’s these questions and figuring out what the answers might be that gave me my story. I did my best to forget about Dickens and just got on with writing it.

But then a strange thing happened. I recently went back to Highgate to film some video clips to help promote the book and, as I was walking around the streets of Highgate, I came across a blue plaque. For those not familiar with what these are, you see them fixed to certain buildings in the UK to commemorate their connection with famous people. The one I saw is pictured below. It’s a reminder, I think, that wherever you choose to tread in London, especially as a writer. Dickens got there first.