Prior to the founding of the Metropolitan Police of London in 1829, policing in England was a fairly haphazard business. In the provinces, most law enforcement fell to part-time, unpaid (often resentful) parish constables and to poorly paid watchmen (“Charlies”), who patrolled the streets. Then there were “thief-takers,” who pursued lawbreakers—although they were known to collude with criminals, resorting to blackmail and intimidation to frame innocent people. There were also private services (akin to private investigators) and “voluntary associations” that people could subscribe to, for protection from burglary. In 1748, under London’s Chief Magistrate and novelist Henry Fielding, seven thief takers were hired to form the “Bow Street Runners,” who undertook detective work in plain clothes, and in 1792 seven more Public Police Offices in London were created on the Bow Street model.

By 1800, London had grown to a million people, and crime was on the rise, but the English public was leery about an official, centralized policing force, as they might trample upon personal liberties.

However, in 1829, Home Secretary Robert Peel pushed for the creation of a uniformed Metropolitan Police, to join the disparate forces around London into a single administration. Men in the new divisions, known as “Bobbies” (for “Robert” Peel) or “Peelers,” were paid a salary to discourage corruption, and they wore uniforms that sought to reassure the public—a civilian-style blue (rather than army red) swallowtail coat and trousers and a leather top hat. The hat was reinforced with cane, so it could double as a stepping-stool for peering over walls, and the stiff brim could break a man’s nose.

In 1842—five years into Queen Victoria’s reign, and after an attempt had been made on her life—Robert Peel organized the plain-clothes detectives, bringing a new level of professionalism to this group, with established pay and procedures. Most detectives were based at 4 Whitehall Place, which backed onto the cobbled area, Great Scotland Yard.

Nowadays, we tend to think of Scotland Yard as the elite group of the Metropolitan Police. However, in the autumn of 1877, Chief Inspectors Nathaniel Druscovich, William Palmer, and George Clark, and Inspector John Meiklejohn were all put on trial for taking bribes, colluding with a trio of con men, and helping the criminals escape.

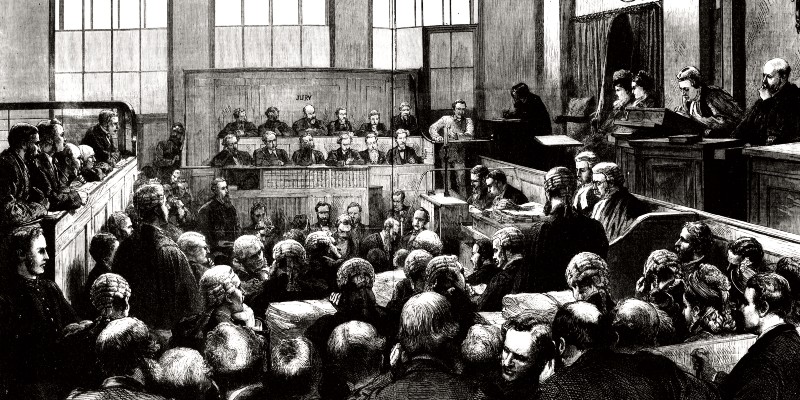

The London newspapers followed the scandal avidly, publishing scornful headlines about the “TRIAL OF THE DETECTIVES” at the Old Bailey courthouse, which lasted nearly a month and provoked huge public outrage. Three inspectors were sentenced to prison and hard labor; Clarke was acquitted, but he retired immediately afterward.

These four men weren’t rookie detective-inspectors. Among them, they had 88 years of experience … which makes one wonder what else they’d been up to over the years. (Hm!)

The con was begun in 1876, when a forger named Benson was released from prison and contacted two brothers named Kerr. Together they created a French newspaper, Le Sport, which recommended to its readers a betting man named “Mr. Montgomery,” who claimed to be so proficient at picking horses in the races that bookies would no longer accept his bets at fair odds. He was looking for people to place bets for him; and through a complicated back-and-forth with cheques, the con men ended up with legitimate tender, and the defrauded victims with worthless paper.

An unsuspecting French countess sent “Mr. Montgomery” £10,120 pounds (roughly $1.5 million today) and was preparing to send him another £30,000, until her suspicious banker warned that she was being duped. She hired an English solicitor, who took her tale to Scotland Yard. When Benson and the Kerr brothers were discovered in London and the warrants drawn up, it was the inspectors’ duty to arrest them, but Inspector Mickeljohn had known William Kerr for years, Inspector Druscovich owed the Kerrs £60, and all four inspectors had all been well paid to look the other way. So instead, as one paper reported, “Kerr and his friends bade the officers a friendly farewell, and departed in various directions.” Eventually the criminals were caught and the inspectors arrested.

As you’d expect, the public’s trust in the Yard was shredded, and Parliament directed a Departmental Commission on the State, Discipline, and Organisation of the Detective Force of the Metropolitan Police (the Victorians loved their long committee names) to embark upon an investigation. There was talk of shutting down the plain-clothes division, but instead it was reorganized into the Criminal Investigation Department (note the omission of the sullied word “detective”) under a new director, C.E. Howard Vincent, in 1878.

Director Vincent was an unusual choice, for he had never worn a police uniform and never solved a case. The second son of a baronet and a former newspaperman, Vincent had studied the police department in Paris. To the Parliamentary Commission, Vincent was a new broom that could sweep the Yard clean, and he did just that, writing a new procedure manual and establishing stringent policies. But public distrust lingered for years; for example, in 1880, Reynold’s News proclaimed, “Scotland Yard persists in holding out every inducement to policemen to trump up charges in order to obtain the rewards that are given to those who procure the most convictions.”

When I heard about the Trial of the Detectives, I wondered, how would an inspector cope with the aftermath, with having to solve a case when the public and the newspapers were ready to pounce on his every error?

Down a Dark River begins in March 1878, shortly after this scandal has rocked the Yard. Inspector Michael Corravan is one of the few senior inspectors remaining, as most of them are in jail. A former thief, bare-knuckles boxer, and dock worker, Corravan was raised on the rough streets of Whitechapel—in stark contrast to the polished Director Vincent. Their complicated but ultimately collaborative relationship is one of my favorites in the book.

***