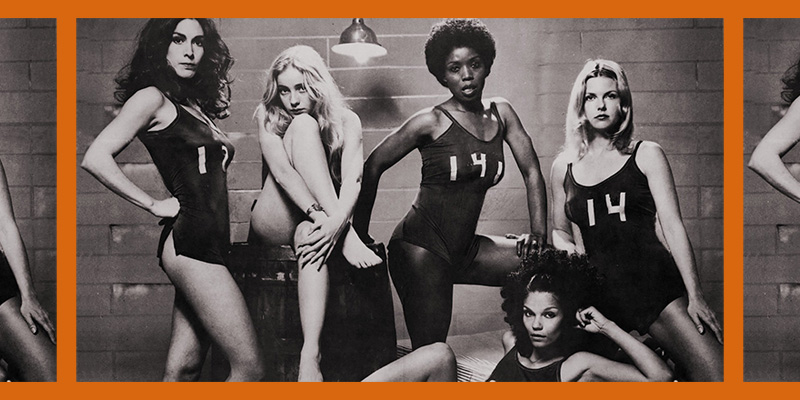

Caged Heat (1974) is a perfect directorial debut film. While it seems on the surface that it mostly exists to provide the exciting tropes of a women in prison film from New World Pictures, it also contains (albeit in embryonic form) a wide array of the technical and narrative elements that would define its creator, Jonathan Demme, as a distinctive and delightful voice in American cinema.

Before I analyze Caged Heat, I want to delve a little more into what I consider to be a great directorial debut film. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a highly influential classic, like Citizen Kane (1941) or Breathless (1960). Instead, I believe that a great first film should impress you, demonstrate the unique traits of a director’s creative voice and, most importantly, make you want to see what its creator will do next. It’s the first stone upon which a director builds a house, or an appetizer before a main course. Films like Shallow Grave (1994) and Going in Style (1979) fit that model as intriguing films which prefigure more accomplished and financially successful work from their respective directors Danny Boyle and Martin Brest. It is a model into which Demme’s first film fits as well.

Caged Heat is about Jacqueline Wilson (Erica Gavin), who receives a 40-year sentence for her role in a drug trafficking operation. Newly imprisoned, she bonds with fellow inmates Pandora (Ella Reid) and Belle (Roberta Collins) and faces off against the tough Maggie (Juanita Brown). Wilson also must deal with a sadistic warden named Superintendent McQueen (Barbara Steele) and her brutal staff as the idea of escaping becomes increasingly necessary.

In the opening sequence of Caged Heat, Demme unintentionally follows Billy Wilder’s second rule of screenwriting: “Grab ’em by the throat and never let ’em go.” Within the first five minutes there has already been a death by gunshot, an exciting foot chase, and colorful introductions to the brutal yet intriguing prison as well as Wilson’s fellow inmates. Demme would go on to have many great opening sequences in his films, such as the elegant tracking shot of New York City as David Byrne and Celia Cruz sing “Loco De Amor” in Something Wild (1986) or Jodie Foster going through the obstacle courses at Quantico in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Demme’s opening sequence for this film is an overture to all the overtures he would craft in his later work.

From a technical perspective, Demme mostly follows the rules which his mentor and producer Roger Corman laid out for him at a lunch before he began production on Caged Heat. In an interview for Corman’s memoir How I Made A Hundred Dollars in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, Demme noted that Corman advised him to “Find legitimate, motivated excuses for moving the camera but always look for ways to move it.” This influenced him to include many tracking shots in Caged Heat, albeit unshowy ones. They are always brief yet add a welcome sense of movement which goes well with his story’s propulsive rhythm. The editing, with its many quick cuts to accentuate the film’s action sequences, also feels like a stellar example of the type of technical style which made many other films from Corman’s New World Pictures so exciting.

But Demme’s adherence to Corman’s teachings does not prevent the numerous appearances of the most famous element of his own visual style, which is his extreme close-ups. That type of shot, which places the subject in the center of the frame and makes it seem as if they are looking directly at you, is heavily associated with Demme and reflected his desire to immerse you in the world of the film as well as the consciousness of his characters. The first time he uses that type of shot in this film, it is an embryonic version which shows Wilson gazing into the camera as a judge sentences her to prison. It’s a beautiful image, but there is just a little too much distance between her and the camera for it to be a true Demme extreme close-up. Later, however, Demme and his director of photography Tak Fujimoto (working together for the first time) use what would become a more familiar version of it to film Maggie yelling at an off-screen fellow inmate. It’s thrilling to see Demme and Fujimoto develop and refine their signature shot at the beginning of their careers, as if they are learning on the fly how to create something which would have great emotional impact in more famous films like in The Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia (1993). “It’s fun to see that we were into that stuff right off the bat,” noted Demme on the commentary track for the Shout Factory Blu-ray of this movie.

Beyond his technical style, Caged Heat featured the first appearances of a lot of Demme’s narrative interests. He was arguably the best American director of live performances. He incorporated many of them into his narrative films in addition to his “performance films,” which consist entirely of people just performing for an audience. It seems appropriate, then, that his directorial debut depicts two types of performances which he would later capture to more spectacular effect. To entertain their fellow inmates, Pandora and Belle put on a drag show. It mostly consists of them cracking jokes, but they also sing together briefly. The conventional way that their quick duet is shot and edited is a far cry from the thrilling sequences of Stop Making Sense (1984) or Storefront Hitchcock (1998), but it is still fun to see this minor moment and think of it as the ancestor to all the incredible musical performances that Demme would go on to film.

More successful is the cabaret-esque performance that Superintendent McQueen gives in a dream sequence. Clad in a showgirl outfit and able to walk (she is otherwise a wheelchair user), Superintendent McQueen spins around as she lectures her prisoners on her attitudes towards life. It’s a fantastic sequence that allows Steele to cut loose and show off a passion Superintendent McQueen otherwise never displays. This sequence may lack the routine of intercutting close-ups of a performer talking to themself which Demme and his editor Carol Littleton would later use to brilliant effect in Swimming to Cambodia (1987), but it shares a similar interest in depicting how a single person can navigate the unruly workings of their life by giving a monologue. It is also a very Demme-esque touch that the repressed and miserable Superintendent McQueen is at her happiest when she performs in front of people.

In terms of performance, Caged Heat also displays Demme’s great eye for unconventional yet effective casting decisions. The same sensibility that would later lead him to cast Anthony Hopkins as the disturbing Hannibal Lecter after seeing his performance as the kindly doctor in The Elephant Man (1980) is present here in his choice of Gavin as Wilson. She had not played the lead role in a film since her electrifying performance in Vixen! (1968), but Demme offered her the part without an audition. It was a good choice, because her natural charisma and sensitivity make you want to see whatever she does next. Some of Gavin’s best moments are silent, such as look of delight she has during a dream sequence or her blank stare after a horrible bout of shock therapy. Demme gave her a rare chance to show how good of an actor she is, and it’s a tantalizing glimpse of what she could have done if more people had that director’s eye for her talents.

There is another, more subtle characteristic of this film’s protagonist which foreshadows the most famous female character in a Demme film. From her first scenes, Wilson consistently displays great compassion. Whether it’s trying to save one of her fellow criminals in the opening sequence or refusing to leave an injured guard after a fight, she constantly tries to help others. Most of the time this desire to help backfires on Wilson, like when she gets arrested or sentenced to intense shock therapy. But she tenaciously holds on to her desire to help people so much that she not only returns to the prison to rescue Belle but convinces Maggie and Alice to go with her. Demme’s biographer David M. Stewart adroitly noted that this desire to rescue people is one that Wilson shares with Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Wilson isn’t quite a protype for Starling (they’re on opposite sides of the law for one thing), but the fact that Demme’s first protagonist is also a young woman with a troubled background whose key trait is a keen drive to liberate other people (especially women) shows just how good of a choice he was to direct the film for which he is still best known.

Jodie Foster once called Demme her “favorite feminist director,” and he laid the groundwork for that reputation with this film. Many of the important character archetypes – the protagonist, her allies, her secondary antagonist who becomes her ally – are filled by women. They are all as complex and likeable as male characters. But the female character who expands and deepens Demme’s feminism the most isn’t a heroic one, but the film’s antagonist. Superintendent McQueen is one of the film’s best characters. She upends ideas about what disabled people can do by being an authority figure as well as what women can do by being the film’s smartest and most interesting antagonist, who gets to deliver such menacingly snappy lines such as “we punish here as well as correct.” If the central tenant of Feminism is that women have the right to be equal to men, then Demme proves it correct by making Superintendent McQueen the villainous equal of any male antagonist.

I would not argue that Caged Heat it is a perfect film. It’s too “nasty, brutish, and short” (to quote the philosopher Thomas Hobbes) to achieve the kind of narrative and aesthetic beauty which cause films to regularly wind up in the canon of great cinema. Even Samuel Fuller, a longtime friend and mentor to Demme who influenced his use of extreme close-ups, wrote dismissively of it in his autobiography A Third Face. But Caged Heat has few equals as a calling card that announces the stylistic and narrative interests of the person who made it. When you watch it, you cannot help but ask yourself what its director would do next. Few filmmakers would go on to give as many interesting answers to that question as Demme.