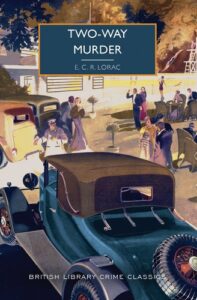

The appearance of E.C.R. Lorac’s Two-Way Murder as a British Library Crime Classic represents a landmark in vintage detective fiction publishing. A novel by a well-regarded female author is finally seeing the light of day after being ‘lost’ for more than sixty years. The Crime Classics series has achieved astonishing success around the world, as long-neglected books have returned to print in highly collectible new editions with lovely period-style cover artwork. A very wide range of books originally published between the 1920s and the 1960s have found an enthusiastic readership in the twenty-first century. But Two-Way Murder is the very first novel in the series that has never appeared in print before.

So who was E.C.R. Lorac? The enigmatic pen-name concealed the identity of Carol Rivett, or more precisely Edith Caroline Rivett (1894-1958). She was not regarded as one of the Queens of Crime who flourished during the “Golden Age of murder” between the world war, but nevertheless she enjoyed a career as a detective novelist over a span of more than a quarter of a century. Before the Second World War, she earned election to membership of the prestigious Detection Club, and later served as Club Secretary. The pleasantly persistent Inspector Macdonald first appeared in The Murder on the Burrows (1931) and solved crimes in the books which came out under the Lorac name until the posthumously published Death of a Lady Killer (1959). As Carol Carnac, the author also created a second long-running series cop called Julian Rivers.

From the time I became series consultant to the Crime Classics—it’s hard to believe it was nine years and a hundred books ago—I hoped to bring Lorac, along with a number of other writers who have long appealed to me, back into print. My interest in her work dates back to my youth, when my parents were keen fans. They were fond of Morecambe, where I spent the first two holidays of my life; the resort is just down the road from Lunesdale, where Lorac lived and set their favourites among her novels. Those books had, however, already vanished from the shops and libraries and from my twenties onwards, I would buy copies for my parents whenever I spotted them in second-hand shops. But they weren’t easy to find. Lorac had well and truly blipped off the radar. I did, though, give a hat-tip to one of her most memorable plots in a book of my own, the fourth Lake District Mystery, The Serpent Pool: the better-known Lake District is a few miles north of the (comparatively) unfrequented valley of the river Lune.

It took some years for the British Library’s in-house heir-hunters to trace the present day copyright holder, but finally we were able to publish her atmospheric 1930s mystery Bats in the Belfry. The success of that book led swiftly to the republication of more Loracs. To my pleasure and surprise, she has now become one of the most popular—if not the most popular—authors in the series. We’ve published a diverse mix of her titles, including some of her early books set in London, such as the intriguing These Names Make Clues, and a war-time mystery, Murder in the Matchlight, as well as the Devon-based story Fire in the Thatch and Fell Murder, which is set in Lunesdale. She moved to that part of Lancashire (to be close to her sister and brother-in-law) in the early 1940s and remained there for the rest of her life. One Carnac title, Crossed Skis (she was an enthusiastic and capable skier) has also appeared in the series. Her evocation of place is a particular strength, while her characters are believable, perhaps in part because she based many of them on people she knew.

Until recently, little was known about her life and few if any photographs of her had appeared in the public domain. I’ve been fortunate to meet a family in Lunesdale whose members were close to her; their generosity and support has enabled me to discover much more about a woman whose life was as quietly interesting as her books. I’ve also managed to chart the real-life equivalents of some of the locations which she fictionalised.

I first became aware of the existence of the unpublished typescript of Two-Way Murder more than a decade ago, through James M. Pickard, a leading dealer in rare books and also a discerning collector. James has a particular specialism and expertise in Golden Age fiction, and many of the most sought-after and valuable vintage first editions have, over the past twenty years, passed through his hands. He acquired a number of rare Lorac manuscripts, including this one, at a country auction. It must have seemed like a treasure trove, although at that time only a limited number of crime fans were aware of the merits of Lorac’s writing. I was therefore fascinated to learn from James about a hitherto unknown Lorac novel.

This prompted me to write a post about Two-Way Murder on my blog, ‘Do You Write under Your Own Name?’ back in September 2009. I expressed the hope that the manuscript might one day be made more widely available, although at that point there seemed to be no realistic prospect of my ever playing a part in making that happen. Two-Way Murder was clearly worth investigating. My main reservation was that, if a book has never been published, it’s usually for a good reason; perhaps it was written towards the end of the author’s life, at a time of waning powers, and the publisher rejected it.

Two-Way Murder had never been in print and so far as is known, there is only one copy of the typescript in existence.The British Library did not have a copy of the manuscript. As one of the UK’s legal deposit libraries, it is entitled to receive all published books—but Two-Way Murder had never been in print and so far as is known, there is only one copy of the typescript in existence. However, thanks to the generous co-operation of James Pickard, it became possible for both the British Library and myself to read the book.

When I studied Two-Way Murder, it seemed clear that its disappearance from sight was not the result of feeble storytelling at the tail end of the author’s career. On the contrary, Lorac seems here to have been making an attempt to break fresh ground. The writing is crisp, despite the fact that if there was any editing, it must have been minimal. The author’s name on the cover sheet is ‘Mary Le Bourne’—evidently a pun on ‘Marylebone’ in London—and the police detectives in the story are not the investigators familiar from the Lorac and Carnac series. The setting on the south coast of England is also something of a departure from the backgrounds to most of her post-war novels. Was she trying to write a different type of detective story? Might she have had in mind a distinct series featuring Waring, the likeable police officer who solves the puzzle? The answer to both questions may well be yes.

The mysteries of the whodunit puzzle in Two-Way Murder are matched by those surrounding the history of the typescript and its failure, until now, to achieve publication. I’ve undertaken some detective work of my own, although I feel sure that further clues remain to be discovered.

We can only speculate, but the first point to make is that the book was written shortly before Lorac died. Internal evidence suggests that the events of the story take place in the January of either 1956 or 1957. She died in 1958 after a short period of ill-health brought an end to a previously active life. She left one novel substantially written but incomplete; in the year of her death, no fewer than three new books of hers were published. Two more followed into print in 1959. It seems likely that this book was finished after those novels were submitted.

One possibility is that she had not sent Two-Way Murder to her usual publisher at the time of her death, and that in effect it simply fell through the cracks. Or perhaps she wanted to try a different publisher, carving a fresh identity as Mary Le Bourne and launching a new series with a fresh background and likeable new detective.

One of the manuscripts that James Pickard handled a decade or so ago was Lorac’s autobiography, which remains unpublished. It is just conceivable that this answers some of the questions about this book, as well as casting further light on her life generally. So far, unfortunately, I haven’t been able to trace the present whereabouts of the autobiography; apparently it has passed through several hands over the years. I hope that one day it too will turn up, enabling us to gain a fuller understanding of a talented woman.

The typescript of Two-Way Murder bears several amendments in Lorac’s hand, but there remain a few infelicities that would probably have been picked up during a thorough professional edit – examples include occasional repetitions of words and phrases. I have not attempted to edit the manuscript for style. It seems preferable to release the book in the form in which the author left it.

What of the story itself? It opens on a dark and misty winter night, with the central characters eagerly looking forward to a ball that is a highlight of the local social calendar. Two men are making their way to the ball by car. Nicholas Brent, an ex-naval commander who now runs an inn in the neighbourhood, has offered a lift to barrister called Ian Macbane, who comes from out of town but has local family connections. Their conversation turns to Dilys Maine, a beautiful young woman admired by both of them, and also to the strange disappearance of a local girl, Rosemary Reeve.

Nick Brent has arranged to drive Dilys home, but on the way back after the ball, he brakes to avoid hitting a corpse that is in the middle of the road. When he goes to a nearby house to call the police, he is knocked out by a man he presumes to be Michael Reeve, brother of the girl who went missing.

These events set in train a police investigation which is hampered by the reluctance of witnesses to tell the truth. Who is the deceased, and what could have been the motive for killing him? These are the central puzzles, but there are a number of subsidiary mysteries. Lorac shifts the perspective from which the story is told time and again, keeping the reader off balance as the plot thickens like coastal fog. This adroit use of viewpoint is—as with several of Agatha Christie’s finest mysteries—crucial to distracting the reader’s attention from the identity of the culprit.

Although Two-Way Murder was written more than a decade after the end of the Second World War, and differs from the author’s other fiction in some respects, nevertheless it bears a much closer resemblance in terms of style to the Golden Age detective writing which Lorac first embraced in the early 1930s than to the work of younger authors such as Julian Symons, Margot Bennett, and Shelley Smith, who focused increasingly on homicidal psychology in the novels they produced at around the time this book was written.

In short, Two-Way Murder is a good, old-fashioned whodunit which displays many of the virtues which have won Lorac so many new admirers in recent times. Its journey into print has been even longer and more winding than the roads which play a part in the storyline, but it is thrilling to see it in print at last. The novel’s belated appearance makes a fascinating contribution to crime fiction heritage. And I like to think that the author herself would be gratified that her final completed book has not been lost forever.

***