I saw a ghost show before I knew what one was.

At some point when I was still a kid, I was taken to a local drive-in movie theater and saw some 1960s-era horror movie in re-release. At some point during the movie, monsters – local teenagers in cheap rubber masks – ran among the parked cars.

I was alarmed.

And while the presence of pimply-faced teens wearing Topstone masks was enough to scare me at that tender age, I wish I’d realized that what I was actually seeing was one of the last manifestations, at least around these parts, of the ghost show, or spook show.

The real ghost shows, dating back to the early days of the 20th century and usually held in hard-top, or indoor, theaters, were much more elaborate than just kids recruited to wear rubber masks at this drive-in.

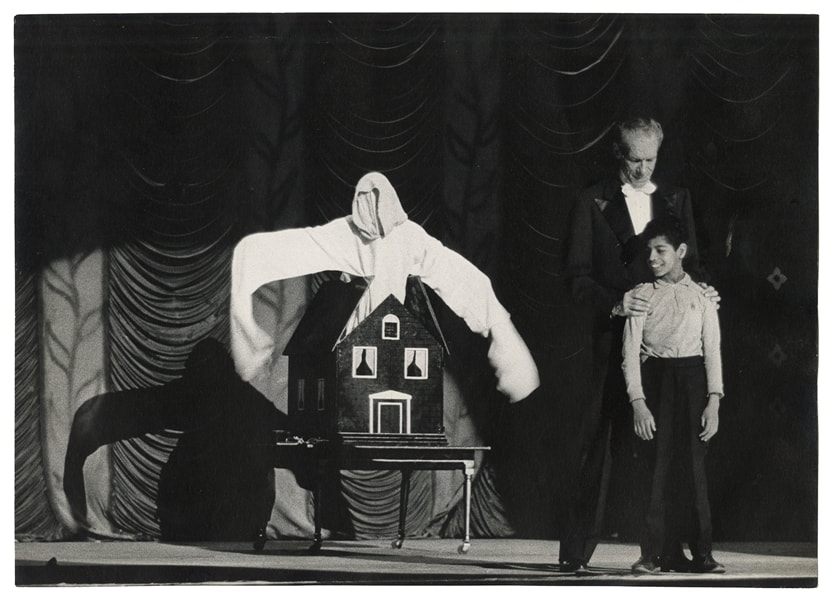

True ghost shows were an evening’s worth of entertainment. Usually starting not long before midnight, these shows were staged in a movie theater and combined a magic act (with an emphasis on horror-tinged magic like swords through comely assistants) and a live-action horror skit (Frankenstein’s monster lurching around the stage) and a blackout period (in which phosphorescent-painted “ghosts” were flown on wires over the heads of the audience) and, usually starting at midnight, a screening of a classic or not-so-classic old black-and-white horror film.

With their emphasis on live and filmed entertainment as well as audience participation, there was nothing like ghost shows in the history of entertainment.

Where theatricality met fakery

For a few decades now, Mark Walker’s early-1990s book “Ghostmasters” (released in 1991, revised in 1994) has been the go-to history of ghost shows and spook shows. Walker dates the earliest forerunners of ghost shows to 1798 France, when a Belgian optician, Etienne-Gaspard Robertson, projected images with a magic lantern. The earliest incarnation of the ghost show shared a history with live theatrics, cinema and photography – and literature.

In 1862, a chemistry professor named John Henry Pepper staged a ghost illusion that ended up in stage productions of Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol.” Walker notes that within a few years, another component of ghost shows, spiritualism acts, had become popular in the United States.

It’s a strange mélange of theatricality, magic and fakery that, as early as the 1900s, included a major component of ghost shows – luminous paint, used to create glow-in-the-dark “ghosts” and “skeletons” that, during the blackout sequences, were run on wires over the heads of excited ghost show audiences. Among the early popularizers of adding “glowing ghosts” to his act: legendary magician Harry Blackstone.

“Ghost shows of the 1930s mainly appealed to young people in their late teens and early twenties,” Walker writes in his book. “This audience, caught in the grip of the Great Depression, was looking for a way to escape from the grinding toil of poverty.”

Like movies, attendance of which boomed in the Depression, ghost shows were a hugely popular draw for the same audience – young people who enjoyed being out late. (Many decades later, the same could be said for midnight movies.)

Ghost show operators perfected their techniques over a period of decades. And while there was certainly some sharing of secrets and practices over the years, it was somewhat remarkable that ghost shows were so different under the leadership of widely varying practitioners yet so similar. Remember, unlike movies, which were released regionally or nationally for anyone to see, ghost shows were like an itinerant medicine show, traveling by truck and bus from Baltimore to Charlotte to Dayton to Indianapolis to Chicago with little fanfare other than some advertising – and a lot of hype. Few film recordings of ghost shows were made. Historians and latter-day fans would love to see a filmed record of these shows, but very few are known to exist.

Zombie jamboree and blood-curdling voodoo

A mentalist named Edwin Charles Peck is thought to have staged the first genuine 20th century ghost show in 1929. Walker’s book speculates that Peck – who toured as El-Wyn – was inspired by the increasingly popular horror films of the silent movie era. El-Wyn’s Midnight Spook Party included a horror film, magic act and the important blackout, which had precedent in mentalist and spiritualist seances that had been popular since the 1800s.

In the early 1930s, El-Wyn toured the nation and his Spook Party was a huge success, bringing in $3,000 a week.

During the 1940s, many of the shows run by El-Wyn and his brethren paused or stopped altogether for World War II. The end of the war brought the shows back with more emphasis on horror. The old Universal horror films like “Frankenstein” and “Dracula” were being re-released and sequels were being made, so ghost show operators began incorporating those monsters – in the form of performers in masks – into their shows. It’s unlikely that the use of those characters was licensed: The spook show operators were established performers but were vagabonds by nature and didn’t take their intellectual property cues from Hollywood executives.

The ”Zombie Jamboree” of spook show operator Ray-Mond (Raymond Corbin) toured continuously from 1946 through 1953. Like the Grand Guignol theater of an earlier era, operators like Ray-Mond did not spare the blood in scenes like when an unwilling patient is operated on by a team of mad doctors. Using a magician’s tricks, Ray-Mond ostensibly cuts off the head of a volunteer from the crowd and, according to Walker’s recounting, runs into the audience, butcher knife in one hand and severed head in the other.

Ray-Mond’s “Blood Curdling Voodoo Show” was advertised thus: “ON STAGE! Show of 1,001 horrors! Weird Women! Unearthly Creatures! Leave the stage and sit in your lap! Ghoul Friends with hex appeal!” A vampire-like “weird woman” was the illustration for the ad.

As shows that were being sold to young people, the hype for ghost shows leaned heavily on appeals to the prurient interests – and leaned heavily on the shaming of people who might be frightened by the monstrous nature of the shows.

Advertising urged young women to find out if their boyfriend was “a man or a mouse.” Young men were advised that because the shows were so scary, their female companions would be so frightened they’d end up in their laps.

In the canniest element of typical ghost show hype, everyone was urged to get a bunch of friends to attend together and “make up a spook party” to ensure that everyone would be safe … and to ensure theaters would sell plenty of tickets.

The Madhouse of Mystery comes to town

One popular ghost show operator, John Edwin Baker, was known as Dr. Silkini, a magician who was touted as “smooth as silk.” Silkini’s standard magic act morphed over the years to include horror elements, such as when an elaborate laboratory set revealed Frankenstein’s monster, and the show’s advertisements promised the Frankenstein monster. The presence of the creature, looking very Boris Karloff-like, boosted nightly receipts to $4,000.

Walker’s book recounts how, in 1943, while Silkini was playing at the Orpheum Theater in Los Angeles, Universal got a restraining order prohibiting Silkini from using their monster – or at least its familiar, square-headed likeness.

Universal and Silkini went to court and the studio won … but eventually licensed Silkini to use the monster. The studio demanded, and received, this credit: “Direct from Hollywood by Special Contractual Agreement with Universal Pictures, Frankenstein – in Person.”

In the 1950s, Silkini had seven road companies touring the country and performing his show.

Silkini very well might have represented the pinnacle of the ghost show, but I have a fond spot for Bill Neff, whose spook show was endorsed by no less a Hollywood celebrity than actor James Stewart.

As early as the 1920s, Neff – a magician – and Stewart were friends. They were residents of Indiana, Pennsylvania, where Stewart’s father owned a hardware store. Stewart and Neff even had a stage act together through high school and for a while after.

During World War II, Neff created his own touring ghost show, Madhouse of Mystery. On stage, Neff did battle with an actress playing Dracula’s daughter in a bit employing the well-established trick of locking a woman in a box and thrusting swords through the sides.

Posters for ghost shows were a riot of images, words and color. Neff’s Madhouse of Mystery posters and ads noted, “See Suttee burned alive on an altar of flame! It’s scary! It’s screamy! It’s screwy! Shake with laughs – shiver with suspense – tremble with thrills! See the Goddess of Voodoo – a zombie nightmare with hex appeal!”

After Neff’s on-stage run-in with Dracula’s daughter, the vampire count himself joined the touring show in 1947 when Bela Lugosi became part of the troupe. Publicity photos show Lugosi, in what looks like his familiar Dracula cape, onstage with Neff. Lugosi later traveled with his own spook show. There’s some online footage of Lugosi recreating elements of his show in 1953 for the TV series “You Asked For It.”

My fondness for Neff no doubt derives from the fact that he brought his traveling ghost show to my hometown of Muncie, Indiana, in 1948. More than a decade before I was born, the show played at the Rivoli theater. I discovered this when a friend and neighbor, John Disher, who was allowed to go through the Rivoli during its untimely demolition in 1987, posted online one of many photos that he took: A ticket for the Neff show, in June 1948, that had somehow survived for nearly 40 years, only to be discarded when the theater was demolished.

I was so taken by the idea of the show, I did research on ghost shows, bought Walker’s book and incorporated the 1948 performance locally into a novel I wrote, “Ghost Show,” which combines a heavily-fictionalized account of my mother’s family in the city back then, overlaid with a serial killer mystery that climaxes not only with a ghost show but a personal appearance by President Harry Truman, who visited the city that year.

Like the theater in real life and in my novel, ghost shows and spook shows are mostly a thing of the past. There are some performers who have revived the practice for limited engagements, but the dozens of performers like Bill Neff, who traveled the country amazing and horrifying audiences, are long gone. They’re remembered, when they are, in Facebook pages and random articles like this one.

It’s hard to imagine a touring ghost show operation now. In today’s world, how would an audience react to a “creature” coming down off a stage to menace a young victim? How many cellphone lights would spoil the secrets of the glow-in-the-dark skeletons and ghosts of the blackout period?

There’s not much about the world of entertainment that’s truly past since Broadway does revivals of classic shows and Hollywood reboots and remakes classic movies. Ghost shows have faded into the history of show business, however, and our late nights are less chilling for their loss.