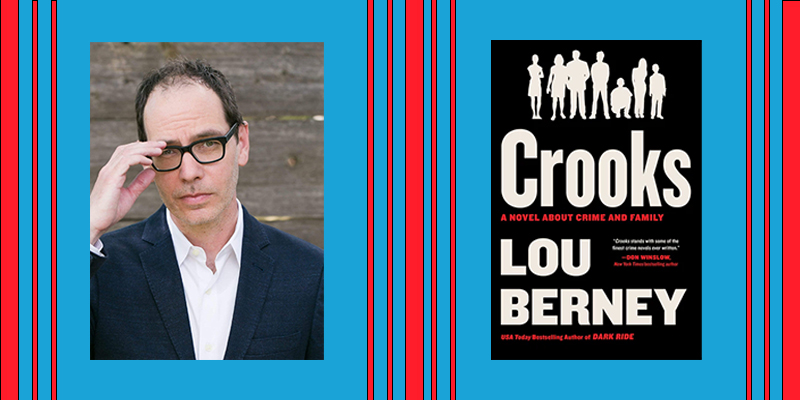

Lou Berney is a crime writer who’s received the Edgar, Anthony, Macavity, and many other prizes for his previous books like The Long and Faraway Gone and November Road. His new book Crooks is something of a departure. It’s a big family epic, a multigenerational tale about many characters taking place over decades– all of whom are, in one way or another, criminals. What’s striking in reading the book is how Berney is able to make the members of the Mercurio clan archetypal without resorting to cliche, making them ordinary even as they lead extraordinary lives. Much of the book is set in the American Southwest, from Las Vegas in the 1960s and 1990s, Oklahoma City in the 1970s, Los Angeles in the 1980s, and rural Arizona in the 2000s, as the characters plot and scheme their way in search of the American dream. Making clear that none of them really know what that means, and conveying just how hard it is to change, even when you don’t have a choice. I spoke with Berney recently about starting writing with archetypes, his fascination with 1990s Russia, and the book’s unanswered questions.

Alex Dueben: The first question with a book like this is, where exactly did it start?

Lou Berney: That’s always a really difficult question to answer. I’ve always wanted to write about siblings and the relationship between siblings. And how that relationship plays out over time. A couple years ago, I just started thinking, how do you make that a crime novel that’s not a sweeping family epic, that’s just another Godfather? I love The Godfather, but that’s not the book I’m going to write. I just started playing around with who the characters would be and how they would interact. It started there, with the characters. Also, places and times I wanted to write about. For some reason, I’ve always been fascinated with Russia in the early 90s, right after the fall of communism. I thought about the porn industry in L.A. in the 80s, and Hollywood.

I kept wondering if the idea for the book started as a family story about criminals, or if it was about shorter ideas that coalesced into a novel about a family?

It was never short pieces. The idea I had was a big family epic. I thought to focus on one key event in each of the characters’ lives. I started thinking about what would that event be? What would that period be? How would those interrelate and not overlap, but also inform each other?

You were very careful to not make the characters into cliches. Making them very different people with very different approaches and skills and paths, but not turning them into cartoons.

It was tricky. You want to make the characters distinct enough, and their paths distinct enough, that they really pop off the page. At the same time, you don’t want to make them a caricature or a cartoon. I played around with a lot of different ideas about the fields they would go into. What kind of criminal influence would carry them forward. I had another sibling originally, a sixth criminal sibling, but that felt too cartoonish. I realize there’s some level of disbelief here, but I wanted to make it as grounded as possible that this family could really exist.

The book starts in Vegas and there’s a familiarity to that story of a low level mobster on the rise. Then he has to flee to Oklahoma City where they raise their kids in a place where they don’t fit and are struggling.

My brother-in-law grew up in a small town in Kansas and his parents would always tell him– and the other kids would be told by their parents– never go to the next town over. Stay out of that town. He found out later it was because it was a mob cool-off town. It’s where the mob sent a hit man to cool off after a hit. That has always stayed with me. I love that idea of putting a criminal somewhere they don’t belong, that’s not their natural habitat. That was the idea. Let’s move them to Oklahoma and see what happens when they try to have a normal family life. Of course no family life is normal, but let’s see how this one is even more kind of messed up.

All families are unhappy. But one of the threads you make clear in how various family members make money, is that there are a lot of things that are not “criminal” but they’re not legal.

That’s a good way to put it. I think so. Because I’m not sure Jeremy does anything– well, let’s just say it’s a little bit of a gray area for several of the characters.

Alice is at the start of her chapter, working at a big New York City law firm, which, well, you know.

Exactly. That’s what I was going for.

Alice manages to be both a criminal and not a criminal all at once. I guess this is what I meant about avoiding some of the cartoonishness. Throughout the book you’re pointing out how that gray area is everywhere.

I feel like that’s the American story, in a lot of ways. The American story is people coming over and exploiting the gray areas– at best! There’s a lot that’s pure illegal. I mean, you have The Godfather, a traditional crime family saga where the American dream is coming over and taking what you want. Not having it given to you. That’s usually when you break a lot of rules and laws, and go your own way. There’s different ways that families and people can go about that.

Each sibling as you said goes in their own direction. Tallulah goes to Russia in the early 90s and you mentioned that time and place fascinated you. Why?

I don’t know why it was always interesting to me. I got out of grad school in ’91 and my wife and I thought, should we go to Russia, and work for an English language newspaper? Part of me kind of regrets not doing that. Who knows what might have happened? I might not be alive right now. I might be in a gulag somewhere. But one of the great things about being a writer is you get to imagine the lives you didn’t lead. I would love to be hanging out with Tallulah in the ‘90s and seeing this world. By writing a novel, I could do that. It also tied into her character. That she’s someone who runs away from pain or from trauma. That would be the place to bury it as effectively as possible. Of course she can’t, because of the inciting incident for her. I wanted it to be a fun and enjoyable novel, but I also wanted there to be some important elements of what it means to deal with your past, deal with where you’ve come from, and where you’re going. How each of them deal with that is the heart of what I was trying to do.

It’s interesting how you describe Tallulah, because she thinks of herself as someone who runs towards things. Who runs towards towards danger, adventure, uncertainty. She thinks of herself in that way, but she is always running away.

I didn’t really have this insight until I was writing it, but almost every one of those four characters– and Piggy too, all five siblings– do not see themselves the way they really are. Jeremy thinks of himself as a certain kind of person that he’s definitely not. Ray is probably the one who sees himself most clearly. But even for Ray, it’s hard. I think that’s a human thing, to not quite have the distance on ourselves to see ourselves clearly. That was kind of fun to play with. I feel like one of the interesting things about characters that makes them so dynamic is that sometimes they don’t themselves know what they’re going to do. That makes it really fun as a novelist.

They were raised with uncertainty. They were raised to be that kind of person. Even if that’s not how they would think of it or how their parents would think of it.

I think that’s right. They’re from an old crime tradition. They grew up and they were taught all the criminal tools they needed. Now they’re trying to struggle with figuring out what to do with those and does that make them happy or not. Do you do you follow in your parents’ footsteps? Do you resist them? Do you chart your own path? Do you combine it with something else? There’s a lot of ways to go.

As you said, none of them quite see themselves clearly. Ray and Alice probably better than the rest of them, but there’s always a gap between how they’re seen and how they think of themselves.

Even Ray, now that I’ve thought about it. Ray thinks he’s stupid, and Ray’s not stupid. Ray has been told his whole life that he’s just a dumb muscle and Ray is not dumb. Maybe Ray is just as bad as the rest and sort of misinterpreting who he is. But that was fun to play with with each character.

The key to Ray’s chapter is that it’s this moment where he stops listening to other people in a sense. And that’s how he becomes himself.

I think that describes a lot of relationships with parents and siblings for a lot of people.

My dad wanted me to be a dentist. He was just like, why in the world would you want to risk your life on writing? I could have never been a dentist. He just picked that out of a hat. My dad was a used car salesman. I don’t know what he was thinking. He just thought that sounded good. Clearly I didn’t have the brains to be an actual doctor, but maybe I could be a dentist. But at some point you either start taking it to heart or you start tuning it out, I think.

You mentioned that the settings were important, could talk a little about how you were piecing this together in terms of like each story. I’m just curious about how you work and the way that these different elements coalesced.

I knew I wanted to write a big family epic. I knew I wanted to cover four or five siblings at different points in their life. In other words, I wanted to have the kind of overlap that you see in the book. Start with everybody, then have an important episode for each of them, and then bring them all back together. I started with the siblings and I wanted to have iconic types. One of the things I love about big crime epics like that is the characters are these archetypes, in a way. I remember starting with an index card that had: The Golden Boy, The Muscle, The Brains, and The Daredevil. My weakness as a writer is I’m going to always complicate things. If I start out sort of complicated, it’s going to go over the edge real fast. I try to start with something extremely simple and concrete, and then I let myself have fun with it. I can’t work the other way around. That’s where I started with these four characters. Then I thought, Jeremy’s the golden boy, of course he’s going to go to LA. He’s got to go to Los Angeles in the 80s– cocaine and MTV and porn. That just made perfect sense to me.

With Tallulah, the daredevil, it made sense to me that she’d go to the most Wild West place on earth at that time, which would have been Moscow. The most dangerous place to do anything, let alone be a cat burglar. With Ray, I wanted to put him somewhere that was a bygone era. I don’t know if you were going to Vegas in the early 90s, but it was just desolate. Nobody went to Vegas in the early 90s. They were at the time trying to convert it to family friendly entertainment and build an amusement park. It was just the most oppressing place on earth, I think. I loved the idea of Ray there working for his dad’s former boss and this old era of swinging Vegas in the 60s was long gone.

Alice, I’m not sure how that really came about exactly, except that I remember going to Slab City long ago, which is a place very much like the commune in Alice’s [story] and just being fascinated by this world of total anarchy. I thought, that’s where I want to throw Alice. Alice, who’s so buttoned up. Who orders the same thing every night. Who will notice if there’s a little too much pepper in the sauce. I wanted to throw her into this world that she’s been trying to leave behind forever, which is the anarchy of her family.

So you always saw Alice as going from being the brains to the buttoned up lawyer who’s looking for order and structure.

Everything she never had as a child. She repudiates everything about her childhood– or tries to. There’s a way for Alice to exist where she can still more or less follow the rules in her new job. She’s a high end private investigator so she’s not really breaking too many laws. But she can be herself in a way that she wasn’t when she was a white shoe lawyer, which was kind of killing her, I think.

It kills most people, I think. [laughs]

That’s my understanding. [laughs]

Alice does a 180 and becomes a corporate lawyer and then relates that doesn’t work. Not just for her, but in life. I feel like she and Tallulah have the biggest transformations in terms of what needs to change in their lives and what it requires.

That’s how I thought of it. Jeremy has this opportunity to change– and he’s totally oblivious to it. Once Ray gets him out of trouble, he’s like, cool, now I’ll go to San Francisco. Jeremy has a chance for change and is oblivious. Tallulah does not want to change, but is forced to. And then realizes that this is a positive thing. Ray wants to change badly, but it’s up to us to decide whether he did change or was able to. Because we’re still not sure at the end, what exactly is Ray’s business? Is he really going down to Mexico to look at tequila farms? I like to think he’s gone straight. Alice, I feel, wants badly to be changed. She’s kind of pulled back in, but she manages to do it on her own terms, I guess.

It’s unclear about the parents by the end. What happens after their story ends in 1978, because at the end of the book in 2016 they’re still together. Who knows what they’ve been doing, but it’s not that stable.

There’s definitely no stability at all. I wanted in that one section in the 70s to have it as much as possible from the point of view of the kids and how they saw their parents. Even though it’s written third person limited, it’s filtered to the kids. So when you get to the end of the book, these people who started out these glamorous, seedy criminals end up just conventional grandparents. I feel like there’s a whole missing book or a whole missing section for the parents. I think there’s things about them the kids will never know or never guess. I like that idea, that we don’t really quite know what happened with the parents between 1978 and 2016.

Even in the 70s, the kids know a lot, and they’re inferring– accurately– a lot. But how much do they know or understand about what happened when they leave?

Piggy’s not the most reliable observer. You can get stuff past Piggy if you needed to.

Piggy has the unfortunate nickname and is the youngest child who is raised by very different parents and is deeply clueless about everything going on around him.

I feel a little too much sympathy with Piggy, I’m afraid. I feel like that’s probably who I am. I’d rather be Tallulah, but I’m probably more like Piggy. I’m hopeful at the end his siblings start opening up to him and he sees the opportunity for a good a good subject to write about. Now they’re going to start letting him in.

He had a normal life. He never got shot at. He never got almost killed. So that’s good.

There’s a way that the parents’ story is very much this alternative American dream, as a lot of crime fiction presents it. What all the kids’ stories are showing is that there’s not the straight world and then the criminal world. There’s a lot more nuance and possibilities that they’re trying to navigate.

That’s what I was going for. This idea of the American way is coming to a place and figuring it out there’s no rules. Or there’s no limitations, if you want to look at it from a more American dream perspective. I think now it’s different. I think there are limitations if you come to the United States. More than there were. It used to be you could be whoever you wanted to be. That’s both a gift and a curse and I think all four kids are trying to struggle with that.

Ray’s story its interesting because it’s about nostalgia. This nostalgia for how Las Vegas used to be. He manages to take advantage of nostalgia and be aware of it all at once.

When I was writing this, a real central concern was the idea of time, and time passing. Time changing things. Or time not changing things. Ray comes up with this idea for a retro Vegas bar that becomes a hit. But he also then becomes the tech guy of the family. He’s the one who buys into the iPhone before it comes out. He’s moving back and forth. Jeremy is someone who is stuck in time. Jeremy’s always going to be 16 years old. Alice finds a way to reconcile that. Tallulah finds a way to reconcile that. The parents find a way to have a completely different life years later. There’s the old F. Scott Fitzgerald quote that there are no second acts in American life. I feel like in this book every character has multiple acts in their life. The beauty of living in America is that you can have multiple acts.

To be fair, Jeremy just has the same act over and over and over again.

[laughs] Yes. Jeremy chooses just to keep doing the same play

___________________________________