Luigi Mangione, the man charged with murdering UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in Midtown Manhattan last month, who currently awaits trial at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, was not the anomalous actor press accounts have made him out to be.

On the contrary, he fits the mold of a recurring type of violent anti-corporate missionary dating back at least to the middle of the last century. Americans have no exclusive claim on violent estrangement, of course, but murderous anti-authoritarian zealots appear to be part of our heritage.

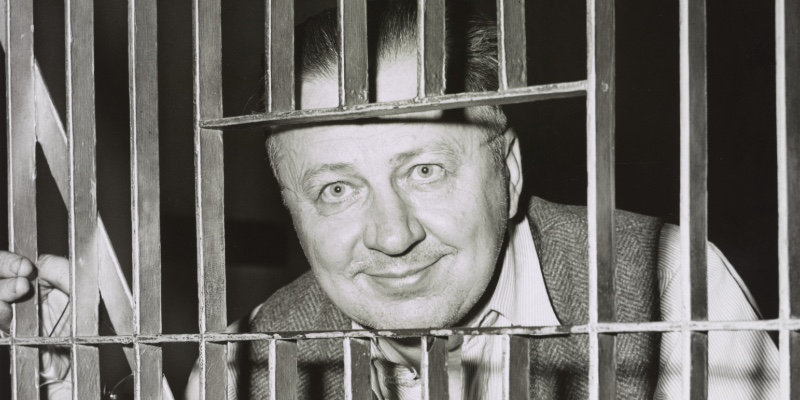

Mangione bears particular resemblance to George Metesky, an aggrieved Con Edison employee who anonymously set off more than twenty homemade bombs, culminating in the late-1950s, after receiving paltry compensation for lung damage and tuberculosis brought on by a power plant furnace blast. Like Mangione, Metesky acted in revenge for what he considered an insufficient medical response by a corporate power. Both imagined themselves as heroes, crusaders on behalf of the ordinary and defenseless. Metesky’s grandiosity and distorted grasp of reality would later be attributed to paranoid schizophrenia.

Ironically, most of Metesky’s bombs exploded a short distance from where Mangione raised his pistol. Metesky’s eighteenth bomb, for example, exploded in the orchestra seats of Radio City Music Hall, just four blocks from the Thompson shooting. The blast, on November 7 1954, inflicted deep puncture wounds on the legs and elbows of two women during a showing of Bing Crosby’s White Christmas. Two boys received contusions.

For years Metesky gloated over his knack for dodging the police, for showing them up. It was easy, almost too easy. He could toy with them— taunt them— with impunity. Even after police apprehended him at his Connecticut home he was convinced that normal rules of law did not apply to him. He floated above such things, like a hero with supernatural powers. There is about Mangioni the same sense of an anti-hero bandit, an outlaw who cleverly evaded authorities, at least for a few days, with his electric-bike ride to Central Park where he walked unobserved by security cameras.

Both men wrote manifestos denouncing the malignant corporate forces aligned against them. Mangione etched his 9 mm shell casings with the words “deny,” “defend” and “depose,” terms commonly employed by health insurers to skirt compensation. After Mangione’s arrest, in Altoona, Pennsylvania, officials recovered a backpack containing the gun, fake identification and a three-page handwritten screed in which he states his “ill will toward corporate America….these parasites had it coming.”

Metesky expressed the same sentiments in a series of rambling, raging letters, published in the now defunct New York Journal American, flagship of the Hearst empire and New York’s most read afternoon newspaper of that period. “I got a sample of what you call ‘our American system of justice’” he wrote. “You people ask me to surrender myself–well sir–who is really guilty–you or I?…. I will bring Con Edison to justice. They will pay for their dastardly deeds.”

Metesky cryptically signed his letters “F.P.” When a detective asked what the initials stood for, he said “Fair Play.” With those two words, barely whispered, the manhunt came to a quiet end.

Metesky became an unlikely folk hero to a certain strain of disaffected protesters. A decade after Metesky had receded from public notice, the Yippies adopted him as a patron saint, occasionally signing his name on violent screeds. Abbie Hoffman wrote his 1967 book, “Fuck the System,” using George Metesky as a nom de plume. A sequel, “Steal This Book,” contains step-by-step instructions on assembling pipe bombs with a flattering attribution to Metesky.

Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, drew inspiration from George Metesky’s long campaign. We know that Mangione, in turn, studied Kaczynski’s 35,000-word manifesto, “Industrial Society and Its Future,” published in The New York Times and Washington Post, and later released as a book. In a Goodreads review, Mangione called Kaczynski’s writings “interesting” and praised him as a “political revolutionary.”

Could authorities have prevented these acts? Hard to say. Metesky assembled his pipe bombs in the privacy of a neglected garage. Kaczynski retreated to a remote cabin. Mangione dropped from sight in the weeks before making his way to Midtown with a gun stashed in his backpack. As criminal profilers tell us, the fanatic plans in silence.

***