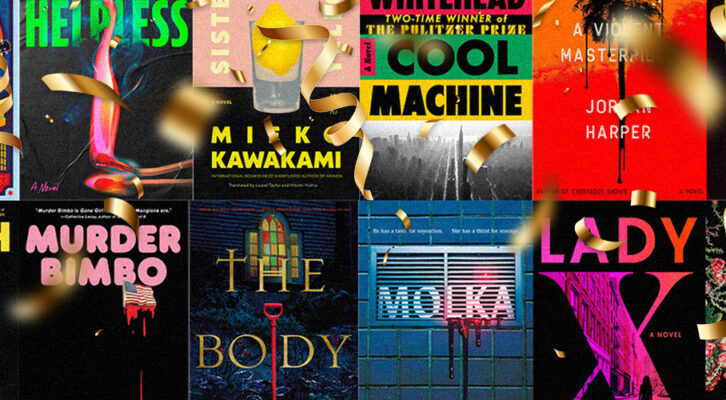

“One of the most authentic, gripping, and profound collection of police procedurals ever accomplished.” – Michael Connelly

Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö were pioneers. First of all, they virtually created Scandinavian noir, and all the giants who followed them happily admit it. Second, with Ed McBain, they revolutionized the police procedural, emphasizing the squad as a whole, people who sometimes argued and fought and failed again and again, but who ultimately complemented one another as a team: “normal people with normal lots, normal thoughts, problems, and pleasures, people who are not larger than life, though not any smaller either,” in the words of Jo Nesbø

Third, and just as important, they took those normal people and used their cases as a way to shine a light on the world as it really is. Any reader of crime fiction today knows that the genre not only entertains, but often acts as a mirror to society; crime does not exist in a vacuum, the books say, it grows out of our systemic flaws. Sjöwall and Wahlöö blazed that trail.

All of that was accomplished with a minimum of preaching (well…usually); a remarkable gift for plotting; lean, propulsive prose that could hit like a gut punch; and bursts of humor that erupted when you least expected it, from sly, dark wit to outright slapstick.

They wrote ten books in all, one a year from 1965 to 1975, but they envisioned them not as individual volumes, but as one long story, thirty chapters each, a three-hundred-chapter saga called “The Story of a Crime.” In it, they tackled pedophilia, serial killers, suicide, drug-smuggling, pornography, arms-dealing, and madness; their characters aged, married, divorced, retired; died; and the country of Sweden itself, as they saw it, veered more and more to the right, the cracks in its “social utopia” growing ever wider, its institutions more geared to the well-off.

At the books’ heart are the men (only men at that time, though a key woman officer is introduced later) of the National Homicide Squad. The central figure is Martin Beck, whom we see progress from first deputy inspector to detective superintendent to chief. He is dyspeptic and dogged; his stomach is bad; and his marriage disintegrating—it is moribund even in the first book, Roseanna (1965), and during the series we see him move from his bedroom to the living room couch to an apartment of his own. He is intelligent, but no super-detective; systematic, but open to sudden inspiration; solitary, but able to talk easily to people; quiet, but with an excellent sense of humor, which he often uses to mock himself:

“Martin Beck, the born detective and famous observer, constantly occupied making useless observations and storing them away for future use. Doesn’t even have bats in his belfry—they wouldn’t get in for all the crap in the way” (The Man Who Went Up in Smoke, 1966).

Also among Martin Beck’s qualities (and the narrator always refers to him as “Martin Beck,” never “Martin,” never “Beck,” unless it’s in dialogue): his good memory; his obstinacy, which is occasionally mule-like; and his capacity for logical thought. Another is that he usually finds the time for everything that has anything to do with a case, even if this means following up on small details that later turn out to be of no significance—because sometimes they are significant. In one case, a two-week-old overheard phone call proves key; in another, the mention of a lost toy; in a third, a sheet of paper overlooked on a desk; in a fourth, a shared name in separate cases which suddenly tie the two together.

Beck also sometimes gets, well, “feelings”—a sense of danger, that something is about to happen. His colleagues call it his intuition, but he hates that word. “Police work is built on realism, routine, stubbornness and system,” he says in The Abominable Man (1971). “Intuition has no place in practical police work. Intuition is not even a quality, any more than astrology or phrenology are sciences. And still it was there, however reluctant he was to admit it.”

Beck is a policeman’s policeman, through and through. That doesn’t mean that he’s happy with the way the police force has been going lately. In 1965, the old local police system in Sweden was utterly changed—nationalized into “a centrally directed, paramilitary force with frightening technical resources” (The Terrorists, 1975). It also significantly coarsened the kind of man recruited into the ranks. As his colleague Lennart Kollberg tells him, “There are lots of good cops around. Dumb guys who are good cops. Inflexible, limited, tough, self-satisfied types who are all good cops. It would be better if there were a few more good guys who were cops” (The Fire Engine That Disappeared, 1969).

Kollberg is not only his colleague, but his best friend, a former paratrooper with a sarcastic manner who refuses to carry a gun after, as a young cop, he accidentally shot and killed a fellow policeman. “Imaginative, systematic, and implacably logical” (Murder at the Savoy, 1970), Kollberg has worked with Beck so long that they know each other’s thoughts without talking. There is no one Beck trusts more, and it is reciprocated: “If you weren’t there, God only knows whether I’d stay on the force,” he tells Beck in The Laughing Policeman (1968). Ultimately, even that is not enough. In the second to last novel, Cop Killer (1974), citing the way the police force has changed, he writes a letter of resignation, and in the last book, The Terrorists, the final words are his: “The trouble with you, Martin, is just that you’ve got the wrong job. At the wrong time. In the wrong part of the world. In the wrong system.”

Kollberg’s antagonist on the force is Gunvald Larsson, a bull of a man, lacking in social niceties, impatient with human weakness, and capable of striking terror in criminals and subordinates alike. He is not popular among his colleagues, but when a house explodes in the early pages of The Fire Engine That Disappeared, it is Larsson who singlehandedly saves the lives of eight people: “Blood-stained, soot-streaked, drenched with sweat and his clothes torn, he stood among the hysterical, shocked, screaming, unconscious, weeping and dying people. As if on a battlefield.”

The only colleague that Larsson actually gets along with, even vacations with, though no one knows why, is Einar Rönn, “a mediocre policeman with mediocre imagination and a mediocre sense of humor” (The Man on the Balcony, 1967). He is a very calm person, however, and hard-working, with a simple, straightforward attitude and “no talent for creating problems and difficulties which did not exist” (The Laughing Policeman), which makes him a valuable member of the team.

Another calming detective with his own unique abilities is Fredrik Melander. The veteran of hundreds of difficult cases, he is a very modest man, even dull, who never gets a brilliant idea but does have a remarkable capacity for always being in the toilet when anyone wants to get hold of him. What makes him singularly valuable, though, is his legendary memory: “In the course of a few minutes, Melander could sort out everything of importance he’d ever heard, seen or read about some particular person or some particular subject and then present it clearly and lucidly in narrative form. There wasn’t a computer in the world that could do the same” (The Abominable Man).

Other colleagues come and go, grow, mature, transfer, retire. They even die: Åke Stenström, the youngest on the squad, is murdered in The Laughing Policeman, causing his widow, Åsa Torell, to pick up the torch and become a police officer herself, to notable effect in the later books (and a one-night stand with Beck himself). So does Kurt Kvant. Kvant and Karl Kristiansson are two spectacularly, often hilariously, inept patrolmen—“Kvant almost always reported whatever he happened to see and hear, but he managed to see and hear exceedingly little, Kristiansson was more an out-and-out slacker who simply ignored everything that might cause complications or unnecessary trouble” (The Abominable Man)—who, despite mucking up any crime scene they’re at, manage to be on the spot for some of the most dramatic events and set pieces in the series. Kvant dies in one of them, only to be replaced by Kenneth Kvastmo, just as inept, though a bit more gung-ho.

And then there are the squad’s superiors, always to be viewed with exasperation or dismay: Chief Superintendent Evald Hammar, an inveterate slinger of cliches and truisms, is counting the days until his retirement “and regarded every serious crime of violence as persecution of himself personally” (The Fire Engine That Disappeared); the man who replaces him, Stig Malm, is even worse—rigid, officious, ignorant of practical police work, his rise due solely to political powers-that-be, to whom he is invariably obsequious, even when they kick him in the teeth; and worst of all, the unnamed National Commissioner of Police, a preening speechifyer whose bright ideas, especially those involving excessive force, inevitably end in disaster and fatalities.

The crimes that face all these policemen, both good and bad, range from the smallest—drunks, break-ins, petty larceny—to monumental—mass murder, serial murder, and political assassination. It is here that Sjöwall and Wahlöö demonstrate their plotting prowess in several different ways:

- A book begins with a small, eccentric moment that leaps into something much bigger, as when a comedy of bureaucratic buck-passing over the dredging of a canal in Roseanna turns into a worldwide hunt for a sadistic killer;

- A storyline that is clearly going in one direction suddenly veers off into something else entirely, catching the reader on the back foot—in The Man Who Went Up in Smoke, Beck is sent to Hungary to search for a missing journalist, but that becomes a plot about international drug-smuggling, and that becomes…well, I won’t tell you.

- A book begins slowly, agonizingly, adding small detail upon small detail, building tension as the notes become more and more discordant, and you know that something dreadful is in store and that it is only a matter of time before things explode. The Man on the Balcony is a masterful example of this. For several pages in the very first scene, we’re with a man on his balcony looking out over the city in the early morning: “The man was nondescript and he was dressed in a white shirt with no tie, unpressed brown gabardine trousers, gray socks and black shoes. His hair was thin and brushed straight back, he had a big nose and gray-blue eyes.” The man is smoking—ten butts are already in a saucer—we see street sweepers, pedestrians, a police car glide silently past, there’s the tinkle of a shop window breaking, then running footsteps. A lone figure walks in the distance, perhaps a policeman. An ambulance goes by. Then the door of an apartment building opens, and a little girl comes out. The man on the balcony stands quite still and watches her until she turns the corner, then he drinks a glass of water, sits down, and lights another cigarette.Oh, you know this is going to be bad, don’t you? And it is.

- The book opens with exactly the opposite, a shocking set piece and tour de force of mayhem, which then leads into many complicated directions. In The Fire Engine That Disappeared, that would be the exploding house and Larsson’s extraordinary heroism. In The Laughing Policeman, it is the discovery of a busful of machine-gunned passengers.

- Two entirely different cases intertwine, seeming to have nothing to do with one another—until they do. In The Locked Room (1972), a task force is trying, not always competently, to solve a rash of bank robberies, while Beck, recovering from a near-fatal wound, is given an abandoned case to keep him occupied, that of a badly decomposed corpse found in a room locked and bolted from the inside. The man died of a gunshot wound, but there is no gun. Watching Beck slowly work out such a classic puzzle during the course of the book is a pure delight. Finding out how it intersects with the other plotline will make you break out into a grin—Sjöwall and Wahlöö have gotten you again.

All of this Sjöwall and Wahlöö limn with impeccable prose—direct, evocative, and effective:

Beck contemplating the details of a case:

“Unpleasant. Very unpleasant. Singularly unpleasant. Damned unpleasant. Blasted unpleasant. Almost painfully so” (The Man Who Went Up in Smoke).

Beck encountering an unlikely counterpart:

“He was a rather young, corpulent man, dressed in a houndstooth-checked suit of modern, youthful cut, a striped shirt, yellow shoes and socks of the same fierce color. His hair was wavy and shiny; he also had an upturned mustache, no doubt waxed and prepared with a mustache form. The man was leaning nonchalantly on the reception desk. He had a flower in his buttonhole and was carrying a copy of Esquire magazine rolled up under his arm.

“He looked like a model out of a discotheque advertisement…

“The secret police were on the scene.” (Murder at the Savoy)

Gunvald Larsson observing anti-assassination security techniques in an unnamed Latin American country:

“The motorcade was moving very quickly. The first of the Security Service cars was already below the balcony. The security expert smiled at Gunvald Larsson, nodded assuring and began to fold up his papers.

“At that moment, the ground opened, almost directly beneath the bulletproof Cadillac.

“The pressure waves flung both men backward, but if Gunvald Larsson was nothing else, he was strong. He grabbed the balustrade with both hands and looked upward.

“The roadway had opened like a volcano from which smoking pillars of fire were rising to a height of a hundred and fifty feet. Atop the flaming pillars were diverse objects. The most prominent were the rear section of the bulletproof Cadillac, an overturned black cab with a blue line along its side, half a horse with black and yellow plumes in the band round its forehead, a leg in a black boot and green uniform material, and an arm with a long cigar between the fingers” (The Terrorists).

And throughout, Sjöwall and Wahlöö keep an unwavering eye on why they created “The Story of a Crime” in the first place—to hold up the crime novel as a mirror to society. Here are only two examples, and they are scorching:

“Stockholm has one of the highest suicide rates in the world—something everyone carefully avoids talking about or which, when put on the spot, they attempt to conceal by means of variously manipulated and untruthful statistics. For some years now, however, not even members of the government had dared to say this aloud or in public, perhaps from the feeling that, in spite of everything, people tend to rely more on the evidence of their own eyes than on political explanations. And if, after all, this should turn out not to be so, it only made the matter still more embarrassing. For the fact of the matter is that the so-called Welfare State abounds with sick, poor, and lonely people, living at best on dog food, who are left uncared for until they waste away and die in their rat-hole apartments. No, this was nothing for the public” (The Locked Room).

From a young woman lost in the cracks, who has committed one last desperate act. “It’s terrible to live in a world where people just tell lies to each other. How can someone who’s a scoundrel and traitor be allowed to make decisions for a whole country? Because that’s what he was. A rotten traitor. Not that I think that whoever takes his place will be any better—I’m not that stupid. But I’d like to show them, all of them who sit there governing and deciding, that they can’t go on cheating people forever. I think lots of people know perfectly well they’re being cheated and betrayed, but most people are too scared or too comfortable to say anything. It doesn’t help to protest or complain, either, because the people in power don’t pay any attention….That’s why I shot him” (The Terrorists).

Phew. So who were Sjöwall and Wahlöö and how did this all come about?

***

Maj Sjöwall was born in Stockholm in 1935. Her father was the manager of a Swedish hotel chain, and she grew up in a top-floor hotel room with round-the-clock room service, a life that she early on came to see as unnaturally privileged. “When I was eleven, I realized that I did not have to live the life my mother had,” she later recalled. The marriage was chilly, and her children unhappy—“I was rather tough. You get tough when you grow up unloved. I had an attitude. I was rather wild.”

At the age of 21, she discovered she was pregnant by a man who had already left her. Refusing the abortion her father insisted on, she accepted the proposal of a family friend twenty years older: “He was nice. I wasn’t very much in love with him, but I admired him.” That did not last. She married again, to another older man—“I think I had a father complex”—who wanted to move her to the suburbs and have more children and—that didn’t work out, either.

Meanwhile, she was making a name for herself as a journalist, art director, and translator for several publications when, a single mother with a six-year-old daughter, she met Per Wahlöö.

Wahlöö, nine years older, was well-known as a journalist covering criminal and social issues, and a committed Marxist, deeply involved in radical political causes, activities that resulted in his being deported from Franco’s Spain (which he no doubt regarded as a badge of honor). He’d also written television and radio plays, as well as several novels dealing with abuses of power and the dark side of society when, working at a magazine in 1962, he met a woman working at another magazine by the same publisher.

The attraction was immediate. “There was a place in town where all the journalists used to go,” she said. “We all went to the same pubs. Then Per and I started to like each other very much, so we started going to other pubs to avoid our friends and be on our own.” He was married, and neither liked the idea of cheating on his wife, but within a year, Per had left her and moved in with Maj and her daughter. Their first son was born nine months later.

It was at one of those pubs that they came up with the idea for the books. They both liked Simenon and Hammett, and realized they could use crime novels to illuminate society from their own point of view. Ten novels, they agreed, thirty chapters each. The first plot came to them on a canal trip from Stockholm to Gothenburg. “There was an American woman on the boat, beautiful, with dark hair, always standing alone,” Sjöwall said. “I caught Per looking at her. ‘Why don’t we start the book by killing this woman?’ I said.”

Seven months of research followed, mapping out the geography, the streets, the distances; taking hundreds of pictures—an accumulation of authentic detail that would characterize every one of their books. “If you read of Martin Beck taking off on a certain flight,” Sjöwall said, “there was that flight, at that time, with those same weather conditions.”

They worked at night, after the children were in bed, at opposite ends of a table in their study, writing in longhand from ten or eleven pm until the children woke up. They had a detailed synopsis in front of them—“If Per started with chapter one, I would write chapter two at the same time”—and the next night they edited and typed the other’s work. “We never talked about the story when we were writing it,” said Sjöwall. “The only things we said were, ‘Pass me the cigarettes’ and ‘It’s your turn to make some tea.’” (“I don’t see how you do it,” an American mystery writer told Wahlöö. “My wife and I can’t even collaborate on boiling an egg.”).

They were very conscious of the style. They didn’t want anything that sounded too much like him or like her—just something that would fit the books and their characters and that would appeal to a large audience.

When the first book, Roseanna, was done, Wahlöö took it to his publisher, telling him, “This is by a friend of mine and I just want to hear what you think.” The publisher wasn’t fooled, liked the book, and struck a deal for all ten of the projected series.

The reviews were mixed for Roseanna. It was considered a bit dark and brutal—“Little old ladies took the books back to the shop,” said Sjöwall, “complaining that they were too awful, too realistic”—and the sales were modest, mainly to young left-wing students. It wasn’t really until the fourth book, The Laughing Policeman, won the Edgar Award for best novel, that the market started to wake up. It was about that time, too, that a review compared them to Ed McBain. In fact, they had never heard of McBain before, but they read some of his books, loved them, and urged their publisher to buy the Swedish rights. He did—and asked if they’d like to do the translations. They ended up translating a dozen of the 87th Precinct novels.

They never got rich from their books. “Back then, no one had an agent,” said Sjöwall, and the royalties were small. “We always had money problems. Sometimes I would lie awake at night wondering how to pay the rent.” Eventually, subsidiary rights—foreign and movie/TV deals—would come in, but most of it was too late for Per Wahlöö.

In 1971, he complained of a swelling, then his doctors said his lungs were filled with water, and eventually they realized his pancreas had burst. He was in and out of hospitals all the time, gradually getting thinner and thinner. In 1975, they rented a bungalow in Malaga, and Wahlöö wrote feverishly on what would become the last book, The Terrorists, doing most of the writing while Sjöwall acted as editor. “Sometimes he would just fall off the chair because he couldn’t write any more. In the morning, the words would be illegible.”

They came home from Spain in March, the book was sent to the printer, and Wahlöö died in June, from a morphine overdose: “Either on purpose or because, you know if it didn’t work he took one more, if that didn’t work he’d take another one. He fell into a coma and never came round.”

He was 48, they had been together 13 years, and never married—“We said, well, obviously marriage is not the thing for us,” she said. “We just knew we really loved each other and loved not having the papers to prove it”—although, apparently, their early publishers billed them as a husband-and-wife team on the book jackets of their English-language editions, to avoid upsetting the sensibilities of those perhaps less liberated than the Swedes.

After Wahlöö’s death, Sjöwall admitted she got “kind of wild for a while. With guys, with pubs,” and then settled down with the kids for a “more bohemian” life. She didn’t mind not having money: “Better free than rich.”

Despite offers to continue the Martin Beck books, she never did, though she did try a couple of other collaborative ventures and happily continued her translations, this time of Robert B Parker’s Spenser series.

She died at the age of 84, on April 29, 2020, in her home on Ven, a small island off the southwestern coast of Sweden. She had no regrets. “This is a part of my life that I didn’t expect,” she said. “I never thought the books would last all my life, or that I’d still be thinking about them after all this time. I think Per would be amazed. I always think of him when we get a prize, or when I have to talk in public. I always think, Per would have loved this.”

At Crimefest 2015 in England, she was the guest of honor, interviewed by Lee Child. When she entered the room, she received a standing ovation.

___________________________________

The Essential Sjöwall and Wahlöö

___________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as anyone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine—but here are the ones I recommend.

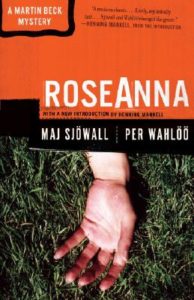

Roseanna (1965)

“They found the corpse on the eighth of July just after three o’clock in the afternoon.”

“Most crimes are a mystery in the beginning,” says the Public Prosecutor at a press conference three days later, but this crime will remain a mystery for far longer than that. The woman’s body lying in the dredger’s bucket is naked, with no jewelry, no identifying characteristics.

“We brought her up eight days ago,” says the local policeman to First Detective Inspector Martin Beck. “We haven’t learned a thing since then. We don’t know who she is, we don’t know the scene of the crime, and we have no suspects. We haven’t found a single thing that could have any real connection with her.”

As the months pass, that’s exactly where things remain, until a chance observation by Beck leads to the first real clue, and then another, and then—to the real enormity of the task in front of them. She was tossed off a tourist boat: “Eighty-five people, one of whom was presumably guilty, and the rest of whom were possible witnesses, each had their small pieces that might fit into the great jigsaw puzzle. Eighty-five people, spread over four different continents. Just to locate them was a Herculean task. He didn’t dare think about the process of getting testimony from all of them and collecting the reports and going through them.”

Yet that is what Beck and his colleagues do, the trail stretching from Ankara to Durban to Copenhagen to Lincoln, Nebraska, the agonizingly slow pace finally quickening, then racing frantically, as it becomes clear who the murderer is—and the drastic measures that will have to be taken to stop him.

The climax to the book is breathtaking, and it shakes Beck to the core. Years later, it will still haunt him. It’ll shake you, too.

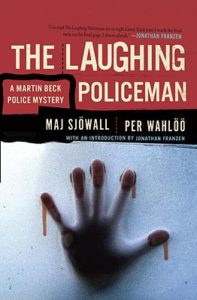

The Laughing Policeman (1968)

Stockholm, curtains of rain coming down, and 400 policemen occupied in keeping Vietnam protestors from the American embassy: “The police were equipped with tear gas bombs, pistols, whips, batons, cars, motorcycles, shortwave radios, battery megaphones, riot dogs, and hysterical horses. The demonstrators were armed with a letter and cardboard signs.”

And in another part of the city, somebody boards a red double-decker bus and machine-guns all the passengers.

There is no discernible motive. There is no connection between any of the people on the bus. For weeks, the squad tracks down each victim’s family, friends, and associates, looking for any clues, but always circling back to one victim in particular: a young, ambitious, up-and-coming detective in their own squad named Åke Stenström. Why was he on that bus so late at night? Why was he carrying his service weapon? Why did his fiancé insist that he had been working very long hours, when in fact crime had been slow? Why did Stenström have photos of nude women in his office desk?

And what did all this have to do with a sixteen-year-old cold case, one of the most notorious unsolved murders in Stockholm’s history?

The answers, when they come, will only cause more death. It is a superb police procedural, full of atmosphere, brilliant plotting, and memorable characters, down to the smallest bit players.

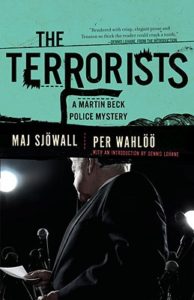

The Terrorists (1975)

“Gunvald Larsson ducked as a mass of flammable objects began to rain down on him. He was just thinking about his new suit when something struck him in the chest with great force and hurled him backward onto the marble tiles of the balcony….

“[He] got to his feet, found himself not seriously hurt and looked about to see what it was that had knocked him down. The object lay at his feet. It had a bull neck and a puffy face, and strangely enough, the black enamel steel-framed glasses were still on….

“[He] looked down at his suit. It was ruined. ‘Goddammit,’ he said.

“Then he looked down at the head lying at his feet. ‘Maybe I ought to take it home,’ he said to himself. ‘As a souvenir.’”

International terrorists are at the core of the series’ final volume, and a bad bunch they are, a professional group who work for hire all over the world, the politics irrelevant, their methods carefully planned and varied. It is to guard against their targeting an important U.S. Senator’s visit to Stockholm that Larsson has been sent to Latin America and had his suit ruined, and things will continue to go against plan all the way through the book, not least of all when the self-regarding Eric Möller, head of the Security Police, takes a list prepared by Larsson headed CS, for “Clod Squad,” consisting of those officers who should be allowed nowhere near the assassination detail, and, mistaking it to mean “Commando Section,” places exactly those officers in the most sensitive positions possible.

This is, however, not the only case of importance facing the Homicide Squad. Another concerns the murder of a prominent pornographic film maker, whose favorite m.o. is to get girls hooked on drugs before press-ganging them into his movies. A third case concerns a naïve young woman who thought she could get money from a bank just by going into any one of them and asking for it, which sets off a chain reaction of event that ends up with her on trial for armed robbery. Thanks to a capable court-appointed lawyer and the help of Martin Beck, she is set free, only to tumble quickly down the rabbit hole of the social welfare system, to cataclysmic and tragic effect.

Who are the terrorists in the book? They are everywhere, destroying the innocent and the guilty alike.

A towering achievement, and a fitting end to an extraordinary series.

___________________________________

Movie and Television Bonus

___________________________________

All of the Martin Beck books have been made into movies, some more than once, mostly in Swedish, but also Danish and Hungarian (starring Derek Jacobi!). They also served as a basis for a Swedish television series that ran for a remarkable 18 years, some of which ran on the BBC in 2015, with subtitles. All ten books also received radio dramatizations on BBC Radio 4 in 2012-2013.

The only English language film ever made was The Laughing Policeman in 1973. It was set in San Francisco and starred Walter Matthau as “Jake Martin” and Bruce Dern as “Leo Larson.” It’s a gritty movie, appropriately gloomy, and is, one might say, “loosely adapted” from the book, though some of the bones remain: the bus massacre, the dead detective, the cold case.

Whenever one of my authors got a movie deal, I always told them just to cash the check, but that if, against all the odds, it actually got made, they should just go to the theater, buy some popcorn, and pretend it was made from someone else’s book entirely. If Sjöwall and Wahlöö ever saw this one, I hope they followed that advice.

___________________________________

Book Bonus

___________________________________

As noted before, after Wahlöö’s death, Sjöwall twice collaborated with other writers on books: in 1989, with Bjarne Nielsen, on Dansk Intermezzo, and in 1990, with Dutch writer Tomas Ross, on The Woman Who Resembled Greta Garbo. The latter was about a visiting governmental minister who turns on a porn movie in his Stockholm hotel, and sees his own daughter. To my knowledge, neither book made much of a splash.

Per Wahlöö wrote eight other, most of them novels before he started with Sjöwall: The Chief (1959), The Wind and Rain (1961), A Necessary Action (1962), The Assignment (1963), Murder on the Thirty-First Floor (1963), No Roses Grow on Odenplan (1964), The Generals (1965), and The Steel Spring (1968). These were mainly suspense novels, sometimes set in the near future, about coups, assassinations, social malaise, and politics, and some of them are still available today in English translations.

___________________________________

American Crime Bonus

___________________________________

Fredrik Melander perusing the report on the bus massacre:

“’We have no Swedish precedents….Unlike us, the American psychologists have no lack of material to write on. The compendium here mentions the Boston strangler; Speck, who murdered eight nurses in Chicago; Whitman, who killed sixteen persons from a tower and wounded many more; Unruh, who rushed out onto a street in New Jersey and shot thirteen people dead in twelve minutes; and one or two more whom you’ve probably read about before.’

“’Mass murder seems to be an American specialty,’ Gunvald Larsson said….

“’I read somewhere that out of every thousand Americans, one or two are potential murderers,’ Kollberg said. ‘Though don’t ask me how they arrived at that conclusion.’

“’Market research,’ Gunvald Larsson said. ‘It’s another American specialty. They go around from house to house asking people if they could imagine themselves committing a mass murder. Two in a thousand say, ‘Oh yes, that would be nice.’”

- The Laughing Policeman

Three policemen puzzle over the small caliber of the bullet used to kill industrialist Viktor Palmgren:

“’A .22,’ Melander said thoughtfully. ‘That seems strange….Who the hell tries to kill somebody with a .22?’

“Martin Beck cleared his throat….’In America it’s almost considered proof that the gunman is a real craftsman,’ he said. ‘A kind of snobbishness. It shows the murderer is a real pro and doesn’t bother to use more than what’s absolutely necessary.’

“’Malmö isn’t Chicago,’ Mansson said laconically.

“’Sirhan Sirhan killed Robert Kennedy with an Iver Johnson .22,’ said Skacke, who was hanging around in the background.

“’That’s right,’ Martin Beck said, ‘but he was desperate and emptied the whole magazine. Fired like crazy all over the place.’

“’He was an amateur, anyway,’ Skacke said.”

___________________________________

Title Bonus

___________________________________

In Murder at the Savoy, the above Viktor Palmgren is shot in the back of the head while speaking to some dinner companions, and falls face first into his dinner, comprised of “crenelated mashed potatoes around an exquisite fish casserole a la Frans Suell.”

Happening to look at the copyright page, I noticed that the Swedish title of the book was Polis, Polis, Potatismos! Surely, that couldn’t be…I thought, and put it into Google Translate.

Sure enough, the original title of Book Six of “The Story of a Crime” was: Police, Police, Mashed Potatoes!

___________________________________

A Policeman’s Lot Bonus

___________________________________

“Being a policeman is not a profession. And it’s not a vocation, either. It’s a curse.”

- Sjöwall and Wahlöö, The Man Who Went Up in Smoke

“Why the hell would anyone ever choose police work as his profession, he wondered.”

- Ed McBain, ‘Til Death

“When constabulary duty’s to be done, to be done,

A policeman’s lot is not a happy one.”

- Gilbert and Sullivan, The Pirates of Penzance