Overload. Just too much. Too many strange occurrences. Too many deaths. Too many special editions. Too many bombs exploding at once. Too many coincidences. Too many unanswered questions. Diego has worked on complicated investigations in foreign countries. He’s courted danger and been grazed by death. He even lost the woman he loved. So he’s not intimidated by the stolen babies story. He knows what he has to do. Remain impartial. Check every fact. Every statement. Every witness. Every document. For however long it takes to get to the bottom of the story. No matter the consequences.

He could give a damn about consequences. It’s only by working that he has been able to continue—or survive, rather—since Carolina’s death. If it weren’t for Radio Confidential, he doesn’t know where he’d be now. After his wife’s murder, he fell into a deep depression and even contemplated ending it all. More than once, he would have finished himself off with a bottle of pills, but he could never go through with it. He was feeling better, until the run-up to the elections. The new government doesn’t know, and will certainly never know it, but they undoubtedly saved his life when they kept his weekly two hours on the air. And now he’s going to screw it all up with his investigation, guaranteed. He can see it coming, ever since he read the tiny piece of paper that David Ponce slipped into his hand at the end of their meeting. Just a few words, but it was enough for him to realize he’s finally got something to chew on. Just the idea has given him back some of his hustle and the will to start over with a clean slate.

“I. Ferrer wants to see me in 48 h to show me files on stolen babies.”

That’s the message the judge passed him in the bar, and it’s a ticking time bomb. The lawyer, Isabel, is clever, and she has obviously done her homework. She contacted the only magistrate with the cojones to help her. Nothing wrong with that, as far as Diego is concerned: since Ponce is his trusted source within the judiciary, Diego can bank on having a first-row seat to what happens next. He’s going to have to proceed with caution, however. Diego can’t risk causing Ponce any more damage than the judge might do to himself if he opens up an official investigation.

Which Ponce is entirely capable of doing, despite the pressure that will be mounting on him from all sides. If the government thinks it can sway him in any way, they are sadly mistaken. Way back when the Socialists were in power (Diego has to remind himself that the fascists were elected only nine months ago), Ponce sent them packing too, when he signed an international warrant for the arrest of Fidel Castro for drug trafficking, money laundering, and crimes against humanity. The ensuing diplomatic mayhem lasted for months. Cuba’s cacique emerged unscathed, thanks to his poor health and his doctors’ assurances—relying on what were most certainly fabricated lab tests and exams—that the harmless old man was senile, couldn’t recall anything, and consequently could not be submitted to questioning. The proof? He stepped down and appointed none other than his brother, Raúl, to succeed him. Yeah right . . .

As soon as his mind was made up to make the stolen babies scandal his new priority—which is to say the second he read Ponce’s note—Diego jumped into the hunt: for information, for witnesses, for evidence, and for time, too. He called the radio station to tell them he was sick and wouldn’t be able to do his show this week. He talked it over with the programming director for a few minutes, and they decided to air a season best-of show in his two-hour slot. A sound editor was requisitioned for the task, and Diego has already sent him some clips that would work well. All of which buys him a few days during which he can immerse himself in the stolen babies story, starting now.

He’s been at Madrid’s main library now for hours. He was there when it opened, and he hasn’t come up for air yet. He’s reading history books, on the Civil War and on life under Franco, studies of government during the regime and political theory, too, and even some philosophy. He wants to have a clear picture of the context before going into the newspaper archives of the period. Diego was born in 1970; he was only a kid when El Caudillo died. He never really experienced the Franco era, or at least he can’t remember it very well, so his first priority is this history lesson.

The problem with any kind of public building designed to serve the needs of researchers and students is that smoking is not allowed there. That means that if Diego wants to go out for a smoke, he has to turn in all of his books, and then when he has finished his cigarette break, he has to request them all over again. Whoever thought of that rule? It’s now been four hours since Diego’s last cigarette, and he’s at his breaking point. He rationalizes that he can have a cigarette, stretch his legs, and clear his mind all at the same time. He can even check his emails and calls too because it goes without saying there is no Internet in the library, as if modern technology could ever disturb the years and years of dust that has accumulated on everything.

Out on the sidewalk, he looks for a bar. It’s going to be lunchtime soon, but he can’t find anything open at this hour. He sure could use a coffee, though. In this part of Madrid, as in many others in this city and other large areas throughout the country, it’s getting harder and harder to find a place to sit and have a drink. The financial crisis wiped out everything. Some pockets of the city are utterly deserted. Entire residential communities too, which were developed willy-nilly by completely ruthless contractors and builders. Perhaps more than any other country in Europe, Spain has fallen on bad times and fallen hard. The country sank, literally. The same country that only a few years previously was cited as an economic model toppled like a house of cards. The politicians said it was globalization, and piss off. The real reason was an economy that doesn’t produce anything anymore and a housing bubble. Buy, buy, buy was their cry to anyone who would listen, and there were many who, after forty-five years of dictatorship and shortages, ran as if for their lives to the banks and the builders. It was those same banks and builders who knew a good deal when they saw one and didn’t hesitate to play the opportunity to their advantage. They gave out credit like chorizos. Twenty-, thirty-, forty-, even fifty-year mortgages. Come on, you need money? No problem, take it! Just spend the rest of your life paying us back. And if you can’t, don’t worry—your children will assume your debt for you. End of story: when the bubble collapsed, and when the foreclosures started, those proud Iberian property owners had no choice but to go live with their parents. When you’re already forty or fifty, that’s tough. Because if being kicked out of your home wasn’t bad enough, a lot of the same people lost their jobs too. Factories shut. Small businesses closed. People with graduate degrees were willing to take any little job for whatever it paid, and millions of unemployed workers are still waiting in line, day after day, at job centers, at welfare, at aid associations, and at soup kitchens too. No roof over their heads and no job either. What a beautiful country, this Spain that played host to the Olympics, this young, modern democracy that rose so high and so quickly. There are some who might take offense at this, but most people are standing in such deep shit that they don’t even realize that someone is responsible for what happened to them. All they can think about is whether they are going to eat, not at the end of the month, not at the end of the week, but today. In other words, it is a return to the past, to being a third-world country. And yet they still voted massively for the APM instead of taking to the streets to smash the whole system to smithereens.

It was those same banks and builders who knew a good deal when they saw one and didn’t hesitate to play the opportunity to their advantage. They gave out credit like chorizos.Diego’s mind races while he searches for somewhere to get his hit of caffeine. After ten minutes of wandering the neighborhood and cursing to himself, he spots a green-and-white sign. He’s going to have to make do with a cardboard cup of coffee-flavored water at Starbucks and pay over five euros for it to boot. Well, it’s better than nothing. He takes his first gulp and then decides to look at his phone. He scrolls through his inbox, sending most of his new emails to the trash (invitations to parties sponsored by all kinds of brands of liquor and telephone companies, press releases for the latest must-read work of fiction, and, of course, spam announcing that he has won a million dollars in Gabon’s lottery). More importantly, there is an email from Ana. That one he reads immediately. Finally, some good news. The detective has managed to speak to Isabel Ferrer. The lawyer is willing to grant Diego an exclusive interview, but on one condition: that he dedicates an entire show to the stolen babies. She will even help him by putting him in contact with someone, whose name she wouldn’t divulge, who will tell him a story that, and she insisted on this point, he is sure to find both moving and chilling. Isabel also wants time to answer the accusations made against her, so she can defend herself and explain why she has taken up this cause. She promises not to grant any other interviews to any other journalist: Diego will be the only one to get this scoop because she has great respect for his work. She agrees to meet him but not for another day or two because, as he might suspect, she has too much to do at the moment.

Diego tosses the rest of his coffee in the trash and walks quickly back to the library. He has a lot to read and less time than he thought to process it all. If the lawyer keeps her promise, and he has no reason to suspect Isabel won’t, Diego’s going to have to pick up the pace. It’s an opportunity he can’t refuse. So what if it messes up his timing a little? He’s thinking already about the trailer for his exclusive report. And the audience numbers it will rake in. It’s going to be a huge success for Diego, and for Radio Uno, which, despite being a public radio station run by directors who are little inclined to bite the hand that feeds them—the APM’s cabinet secretaries and elected officials—would never dream of taking a pass on this story. He’s going to have to wait to find out when the lawyer can meet him, though. And what she’s got to show him.

__________________________________

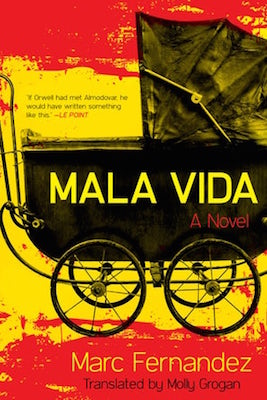

From MALA VIDA. Used with the permission of the publisher, Arcade Publishing. Copyright © 2019 by Marc Fernandez. Translation copyright © 2019 by Molly Grogan