Many of us honing the craft of mystery, crime, and thriller writing sat initially, and still do, at the alter of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. His Sherlock Holmes short stories and novellas are indelibly etched on our minds. How joyous when the two-volume annotated Sherlock Holmes reappeared after being out of print for years; for a time it was available only in rare and used book stores, when one was lucky enough to find it.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s best-known novella, The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902), sets the stage for mystery, crime, and thriller writers wanting to pose the following question in our efforts: Man or Beast?

Placed in the gloom of the English moor, The Hound of the Baskervilles features, in addition to vivid descriptions of distant and horrible sounds, a plot whose tension builds palpably. At its climactic moment, with Sir Henry Baskerville starting his late night, post-dinner-guest jaunt across the pitch black moor despite rumors of an ungodly animal prowling the countryside, the following thought leaps to mind, “no don’t, Sir Henry… don’t walk home… DON’T!”

At the center of Conan Doyle’s famous story is indeed a beast: a huge, demonic hound. The dog, a Great Dane taught to hunt down and terrorize humans and covered with phosphorescent paint, turns out to be cruelly used by the story’s antagonist—forced to commit mayhem and murder at its master’s behest.

What a terrifying read The Hound of the Baskervilles is; the best of the movie versions are equally scary to watch. At the root of the unease, of the distress we experience from the tale, is the ever-present, ominous feeling that a creature is out there and after us. Not something supernatural or alien. Virtually all of that post-dates Sherlock Holmes. Nor a robotic or anything man-made or otherwise created through human ingenuity. No, the fear comes from imagining that one of nature’s own predators, something ordinarily found in our natural environment, is hunting us down.

Terrestrially, we have to contend with bears and the great cats—lions, tigers, jaguars, leopards, cheetahs, and cougars. For young children, the list includes coyotes, dingoes, hyenas, and wild dogs. It doesn’t help to know that any one of these terrestrial predators can run us down. Easily. The cheetah is the fastest land-based animal in the world. And do you think the enormous, lumbering grizzly bear, tipping the scales between 400-600 pounds, is slow? The grizzly can run 30-35 mph, which is much faster than any human being can run, including Olympic-level sprinters. It is scary stuff to consider.

Matters get worse when we are out of our own terrestrial element. Moby-Dick (1851) made that clear well more than a hundred years ago. While we humans might make use of oceans, lakes, and rivers in many different ways, we can never live in them except in our imaginations. We are always just visitors, and often clumsy, ungraceful ones, when in and on the water.

Sometimes we visit with full knowledge of the dangers at hand. Such is the case in Moby-Dick, where the obsessed Captain Ahab, his fate inextricably linked to the quasi-mythological predator he hunts down—a gigantic white sperm whale—drowns, caught in the line of the harpoon sunk into the side of the great beast and pulled overboard.

Other times we are blissfully ignorant of the danger lurking around us until it is too late. Think of the opening scene of Jaws (1974). More than a century after Moby-Dick, and borrowing extensively and shamelessly from Melville’s masterpiece, Peter Benchley’s Jaws brings to life a supernaturally-sized great white shark preying on a small Cape Cod resort town, and the efforts of several men to catch and kill it. Quint, the gruff, eccentric professional shark hunter and boat captain, quickly becomes all-consumed by the hunt, playing the role of Moby-Dick’s Captain Ahab. Quint in fact meets the same exact fate. Entangled in a harpoon rope, he is dragged overboard to his death by the ensnared, mortally wounded shark.

Of all the apex predators on the planet, none produces the fear in us that sharks do. We are in turn fascinated, mesmerized, horrified, and revulsed by them. Their size, their ominous torpedo-like shape, the blank look in their eyes, and the rows and rows of razor-like teeth in many shark species, almost guarantees how we react to them. Adding to our dread of sharks is the stealth with which they strike. When a terrestrially-based attack occurs, we usually see it coming. Not so for sharks. Ask anyone who has survived a shark attack. We cannot ask those who have died by shark attack whether they saw it coming; probably not, based on survivors’ tales and the setting in which many shark attacks occur: a dark and murky ocean.

Turned into a mega-hit film just a few years after the novel came out, Jaws the book and movie did serious damage to the image and reputation of all sharks, and especially the great white shark. The great white, along with a mere handful of other shark species—the bull, tiger, blue, the mind-boggling weird hammerhead (can a marine biologist please explain it), and a few others—on rare occasion attacks humans. Shark attacks are thought to occur out of curiousity, a shark taking a nibble to see if that thing known as a human is tasty, or if excited by splashing or blood in the water. Of course, considering the number, size, and sharpness of the teeth in a shark’s mouth, and the strength of the mandible of a fish that can weigh a ton or more, a shark nibble is often fatal to us.

But the sad truth, as is the case for all other apex predators on the planet, is that sharks have much more to fear from us than we do from them. We have recklessly and inhumanely hunted many shark species to the verge of extinction.

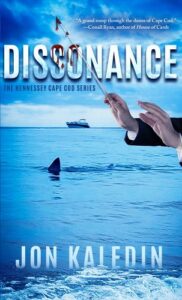

The “Man or Beast” mystery remains unresolved until relatively late in my novel Dissonance. The reasons for doing so were numerous, but first and foremost I wanted to capture the reader’s attention and make the connection, the fascination and fear all of us have in the back of our minds, that there are any number of aspects to our natural environment that are not only dangerous but can be deadly.

A troubling question arose while writing Dissonance. Is it ethically and morally responsible to use certain apex predators, such as great white sharks, in ways that instill horror and fear? To suggest that they are evil and thoroughly bad actors? Did Peter Benchley’s Jaws illegitimately and unfairly stigmatize the great white shark? Has Dissonance, even though it uses the great white shark only as a red herring, done the same thing? In establishing the great white shark as a red herring, Dissonance does not in any way turn it into the supernatural and diabolical animal portrayed in Jaws. Nevertheless, does it perpetuate a public belief and fear about the great white shark that is irresponsible, and that environmentalists might say is done solely to sell books?

In The Hound of the Baskervilles, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle lets us know that the enormous dog, horribly misused by its master, is merely a pawn in a deadly game played by an evil human being. The poor creature is in fact one of the victims in the tale. Reflecting on our relationship with all of the planet’s other apex predators, rather than “Man Or Beast,” perhaps the title to this essay should indicate more accurately who we, as the ultimate apex predator, really are: “Man Is Beast.”

***