For eight seasons and almost 200 episodes, “Mannix” was the epitome of the TV private investigator.

Sure, there have been cool P.I.s (Craig Stevens’ “Peter Gunn” with Henry Mancini’s theme music, full of smooth menace) and affably hot P.I.s (our boy Thomas Magnum) and cerebral consulting detectives (“Sherlock”) and the most charming, hard-luck P.I. on the California coast (“This is Jim Rockford, at the tone leave your name and message …”)

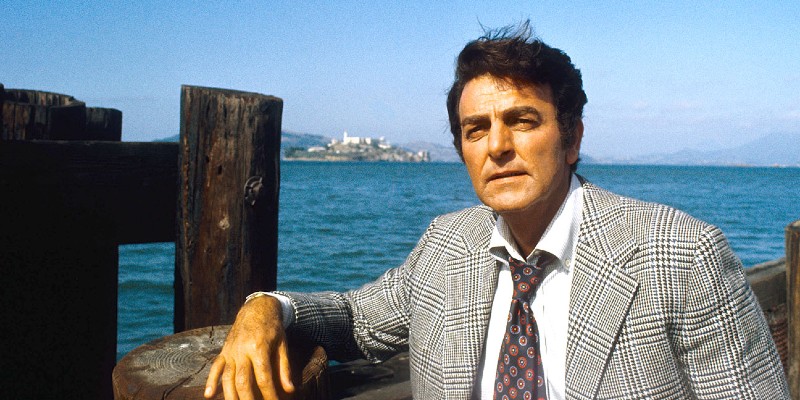

But as far as a play-it-straight-down-the-middle investigator who could take a blow to the head and come back swinging, nobody topped Mike Connors’ “Mannix.” And the show had a hell of a theme too, by Lalo Schifrin.

“Mannix” is more than the sum of its parts, but the parts were pretty good.

From 1967 to 1975, “Mannix” – created by “Columbo” gurus Richard Levinson and William Link and developed by Bruce Geller, who also ushered in “Mission: Impossible” – was solid, formulaic television for its time. It’s not a show that can be watched now for its comedic value, intentional or not, like “Dragnet.”

But while “Mannix” suffered from the episodic nature of TV dramas of the time, there’s a lot to love about the series.

Who is Mannix?

Well, Mannix was Mike Connors, a veteran actor (he passed away in 2017) who played basketball at UCLA for Coach John Wooden. Born Krekor Ohanian Jr. to Armenian immigrants, Connors worked steadily in movies and TV from the 1950s to 2007, when he guest-starred in an episode of “Two and a Half Men.” His final turn as Joe Mannix came in a 1997 episode of “Diagnosis: Murder,” the Dick Van Dyke series, in a sequel to a 1973 episode of “Mannix,” “Little Girl Lost.” Most of the primary cast of that 1973 episode came back for the sequel.

As for Mannix the character, he was a Los Angeles P.I. of Armenian descent who had served in the Army during the Korean War. He was a “white knight” type familiar to readers of mystery fiction: quick to come to the rescue with his savvy and his fists.

In the first season of the series, Joe Mannix worked for Intertect, a large Los Angeles detective agency that used computers – whoever could imagine such a thing? – to help its clients solve their problems. Intertect was run by Joe’s friend Lew Wickersham (played by the stalwart Joe Campanella), who put up with Mannix’s maverick ways because he got results. He got results, dammit! Results!

Mannix was not a good fit at Intertect, where operatives worked out of tidy offices and followed the instructions spewed out of the computer on punch cards. In the first episode, we learn that operatives are only allowed to leave a single piece of paper on their desks. Mannix, of course, has papers and files strewn all over his. He hangs his blazer to block the view of his messy desk from the cameras Lew has installed in every office. Jeez, Lew. 1984 much?

Mannix is not happy at Intertect. In the first episode, “The Name is Mannix,” he practically begs Lew to let him go.

“If I were you, I’d fire me,” Mannix tells Lew.

“You’re my best man,” Lew says.

That episode set the tone for much of the season to follow. Lew assigns Mannix to find the ostensibly kidnapped daughter (Barbara Anderson, later of “Ironside”) of an old-time L.A. mobster played by Lloyd Nolan. Mannix finds, of course, that the case isn’t what it seems. But not before a lengthy, suspenseful sequence on a mountain tram and the climactic scene in which a helicopter menaces the crime heiress and Mannix. Mannix doesn’t punch out the helicopter, but he does win the fight.

And, of course, Mannix finds the young woman without the help of any damn computers.

The first episode establishes a trope than ran throughout the series: Joe Mannix getting hit in the head. More about that later.

‘Mannix’ gets an overhaul

There’s a reason why “Mannix” prospered for season after season, and it has to do with the show’s big change of format in the second season. After the first season at Intertect, Mannix struck out on his own as a private investigator. He set up shop in a comfortable office in a beautiful complex with Spanish-style design. Mannix lived upstairs from the office and would slip into the checked sport coat of the day and come down to grab a cup of coffee first thing each morning.

Greeting him, with that cup of coffee placed on his desk, was his assistant, Peggy Fair, played by the appealing Gail Fisher. Peggy was the widow of a slain Los Angeles cop and when she wasn’t screening callers and passing along info to her boss, she was raising her son.

I’d argue that Fisher’s addition to the show – part of the second season revamp reportedly engineered by producer Geller and Lucille Ball, whose Desilu studio produced “Mannix” – was one of the most important additions to any TV series of its time.

Fisher, who passed away in 2000, was one of the first Black actresses in a prominent role in episodic American TV. She was a groundbreaker, to be sure, but she was also a perfect fit for “Mannix.” Before other actors, including Robert Reed of “The Brady Bunch” as one of Mannix’s cop friends, began making recurring appearances on the show, Fisher brought a sense of continuity, familiarity and family to “Mannix.” She was a steady presence as mother hen for Mannix and figured prominently in some episodes. Not as much as I’d like, certainly, but the nature of TV at the time was that supporting players were supporting players. On “Star Trek,” Scotty got to have one doomed romance of the kind that Kirk got every other episode. Fisher’s presence helped make “Mannix” a classic show.

A quick word about the other woman who figured prominently in the show: Ball, whose studio and savvy business sense spawned some of the biggest hits of the era, including “Star Trek,” “Mission: Impossible” and “Mannix.” Ball was a big booster of “Mannix.” One 1967 newspaper account, accurate or not, reported that Ball pressured CBS to pick up “Mannix” for its first season. Ball reportedly told the network if it didn’t put “Mannix” on its schedule, it couldn’t have Ball’s sitcom. Granted, “Mannix” was a property of Ball’s studio, but her loyalty to it continued for years, including a 1971 episode of her own sitcom in which Connors played Mannix in one of the strangest crossovers ever.

Joe’s Army buddies posed problems

If you watched enough 1960s TV, you noticed a familiar plot device: old buddies of the leading characters showed up and caused trouble. On “Bonanza,” Ben Cartwright’s old pals rode onto the Ponderosa and got the Cartwrights involved in some kind of conflict. On “Star Trek,” Kirk’s brother showed up long enough to die and propel the plot of a single episode.

TV back then was rife with characters who were so important to the leads of the shows … but who were never mentioned before or after they stepped on the stage.

On “Mannix,” Joe’s former Korean War comrades turned up with alarming regularity and it always seemed like they were either in trouble or had murderous intentions toward Mannix.

In a similar vein, in a 1975 episode, Bill Bixby – a TV and movie fixture who in two years would be known as the human half of “The Incredible Hulk” – played Mannix’s fishing pal Tony Elliott. Bixby directed the episode, “The Empty Tower,” and three others that final season.

Once again, Joe gets hit in the head

At some point, Robert B. Parker wrote a memorable article for TV Guide magazine about the television cliché of the cop or private detective who gets shot and shrugs it off. Those bullet wounds, often somewhere in the shoulder or arm, required little more than a sling for the duration of the episode.

Parker noted, correctly, that a real gunshot wound would be devastating to a TV cop or P.I.’s body. Even a shoulder wound would do damage to bone, nerve and muscle and require physical therapy and a long, painful recovery.

Parker – who at some point in his book series has Spenser shot and struggle to recover from his physical and mental wounds – might as well have been writing about Joe Mannix.

A 2007 column in the Washington Post by Neely Tucker notes that someone had tallied the times that Mannix was shot or hit in the head during the 194 episodes of the series. Tucker wrote that Mannix was knocked unconscious 55 times and shot 17 times in the series. (This number does not include the gunshot wound that Mannix survives years later in the opening of the “Diagnosis: Murder” sequel episode.)

Tucker’s column goes on to ask, “Could those ‘Law & Order’ twits take that kind of abuse?”

We all know the answer.

Goodbye, farewell and amen

“Mannix” was a top 20 show in its eighth and final season. But CBS canceled the series before the fall 1976 season. The network’s lineup that fall was certainly different from the way it was when “Mannix” began in fall 1967. Telly Savalas’ quirky and gritty “Kojak” ruled and sophisticated comedies like “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “All in the Family” and “M.A.S.H.” were huge. But “Hawaii Five-O” proved there was still viewership for conventional crime dramas.

But there was no place for “Mannix” on the schedule. Years later, articles theorized that it was actually CBS’ and ABC’s struggles to compete against Johnny Carson in late night that worked against “Mannix.” Carson and NBC’s competitors tried reruns of “Mannix” and other shows after the late news and CBS objected when ABC started airing “Mannix” reruns.

So CBS canceled “Mannix.” Executives thought the brand was cheapened, apparently.

For some of us, “Mannix” never really ended. The show again airs in the late-night hours, now on nostalgia TV channel MeTV, and no one is objecting.

And while I dare say none of us would emulate Joe Mannix in the number of times he was hit on the head, many of us aspired to his cool, his manliness and, most of all, his checked sport coats.

In the 1990s, a reporter colleague and I broke a series of news stories about a state court judge who had unethical relationships with parties in some of the cases in his court. The judge ended up being tried on disciplinary charges from the state and a criminal charge for forgery. He lost his law license and judicial position.

Before that happened, I was trying to track down one of those parties, who was rumored to be working at a local bar, an unsavory place in a building that had seen a murder in years past.

With “Mannix” in mind, I put on my checked blazer and showed up at the place one night. I sat at the bar and subtly – I hoped – asked the bartender questions about the woman’s whereabouts.

I’d be lying if I didn’t admit the “Mannix” theme was in the back of my mind the whole time.

Luckily, I did not get hit on the head.