There are two crimes at the center of Tadzio Koelb’s intense, distilled debut novel, Trenton Makes. The first is a murder. It’s 1946 and a soldier named Abe Kunstler returns home to New Jersey’s capital city after fighting in the Second World War. His wife finds him to be a changed man, and not for the better. She, too has been altered by the war, which she has spent working in a wire rope factory in Trenton. When her husband raises his hand to strike her, the blow, which “she would once have considered it her natural duty to accept” becomes, in her mind, an invitation. She answers his “fishy slap across the face” with “all the great power of the wire rope.” A second blow from her knocks him down. As he falls, his head strikes the corner of the kitchen table, killing him. Suddenly possessed of a new conviction and ambition, she cuts up his body and incinerates it in the basement furnace.

The second crime, following immediately from the first, is one of societal transgression. Having disposed of her husband corpse, the young wife assumes his identity and the attendant privileges of being a man in the twentieth century. He binds his chest and goes to work in a factory with other men returned from the war. And then this new Abe Kunstler sets about finding himself a wife and, ultimately concocting a way for her to be impregnated. The tension in the novel derives not from the first crime, but from the second: will anyone—his wife, his co-workers, his son—discover the truth Abe keeps hidden between his legs? If we accept Laura Lippman’s definition of noir—“Dreamers become schemers”—then Koelb’s book is a literary novel with noir in its heart.

***

Earlier this month, I arranged to meet Koelb in Trenton to walk around the city and discuss its role in his debut. It turned out to be a stormy afternoon, so our walk became a drive. Wearing a military-style cap and overcoat, Koelb, who is in his late forties, looks a little like a retired Prussian cavalry officer who has taken up poetry. In fact, he was born in Washington, D.C. and spent the early part of his childhood in Brooklyn. At the age of twelve, he and his family moved to Belgium, where his father had been offered a job. That move was the first of many for Koelb, who has lived in Uzbekistan, Tunisia, and Madagascar, among other places. A graduate of the University of East Anglia’s storied creative writing program in the U.K., Koelb currently resides in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn with his wife, a public-health consultant, who is studying to be a midwife.

With all of those exotic locales to choose from, I asked, why had he set his book in Trenton? Koelb allowed that he had written an earlier, unpublished novel about expatriates living in Europe, but it had failed to take flight. “Trenton really represented what I wanted to say about the American Century. The optimism, the rise, the hubris, the fall. And how much of that was linked to certain kinds of privilege and lack of privilege and injustice.” He also singled out the Lower Trenton Bridge with its famous sign, TRENTON MAKES THE WORLD TAKES. “In a book about the question, ‘Are we who we make ourselves, or are we manufactured by our culture?’ the idea that Trenton makes the characters seemed really valuable to me.”

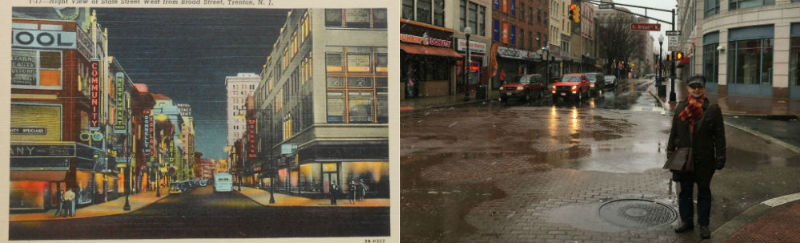

The decline of Trenton as an industrial powerhouse is visible everywhere in the city. Koelb shared with me a postcard he had kept close at hand while he was working on the novel. It shows the corner of State and Broad Streets, the heart of the city’s shopping district, in its midcentury glory: rows of neon signs for hotels and restaurants, with Dunham’s department store anchoring the intersection. Today that crossroads is full of shuttered storefronts with bricked-up windows and “For Rent” signs. The Dunham’s has been replaced by a generic bank building. If the corner has an anchor now, it’s a Dunkin’ Donuts.

Abe Kunstler suffers a similar decline in the second half of Koelb’s novel. Trenton Makes jumps forward to 1971. Abe now works part-time as a deliveryman. He is estranged from his son, drinks too much, and rails against the hippies protesting the Vietnam War: “What the hell do you know about being a man with your long hair and your sissy clothes?” There is a vicious irony to Abe’s wholesale adoption of white male privilege. Koelb told me, “Abe doesn’t want to change the system. He wants to make the system work for him.”

As a result, “Trenton Makes” offers an unconventional look at masculinity and its cultural baggage. An early inspiration was Diane Wood Middlebrook’s biography of jazz musician and bandleader Billy Tipton who was born biologically female but chose a male identity in part to pursue an artistic career path denied to women at the time. “Tipton was by all accounts a wonderful charming human being. I didn’t want to write about that character. I wanted to write about a character who was tortured by this process.” Koelb looked instead to the example of Eugene Fellany who was tried in Australia for murdering his wife, who may have discovered that his birth gender was female. “There are hundreds and hundreds of cases. We’re constantly surprised by this thing that occurs again and again. But it shouldn’t be surprising because of our society and our obsession with men as the most important people in the world. The cult of masculinity leads of course to women who have ambitions [that require them] to become men.”

“The cult of masculinity leads of course to women who have ambitions [that require them] to become men.”The use of noir elements in Trenton Makes seemed natural to Koelb. “Noir fiction always moves past the crime itself to some kind of discussion of how our society produces the imbalances that lead to crime.” While Koelb’s writing heroes include Henry James, William Faulkner, and Ivy Compton-Burnett, he also spoke about the influence of Chester Himes and his admiration for the way Himes built a symbolic structure into his novels. For example, in the Harlem Cycle, Coffin Ed Johnson suffers chemical burns when a criminal splashes acid in his face. “He’s a black detective. He’s working for a white police force in a black neighborhood. He is becoming corrupt through the corruption of the system. And that is shown through these burns, which are grafted with lighter skin from another part of his body. He’s being whitened as a result of his job. The way Himes did that, I thought, was delicate and brilliant even as it was slightly brutal.”

A comparable symbolic element in Trenton Makes is the bandage that Kunstler uses to bind his chest. It is literally a cover-up. He tells his co-workers that he was “wounded” in an accident at a POW camp. Not all of them believe him. “Everyone else gets shot, or stabbed, or blown up,” a factory worker replies. “Something normal that they can goddamn name. But Abe Kunstler? No, not him. He gets himself wounded.” Abe eventually fabricates a detailed lie but the truth is “there was no story; there was just the wound”—the wound of his birth gender. Later Abe is physically wounded in a horrific workplace accident. And that injury, which he can’t hide, begins to unravel the life he has worked so hard to build.

Trenton Makes is being released as the country is in the midst of an intense cultural discussion over sex, gender, and privilege. Though it is set decades in the past, its themes are timely and pertinent. “I think I was looking at a lot of the stuff that we’re looking at as a country,” Koelb said. “I happened to finish my novel in time for us to look at it altogether.”