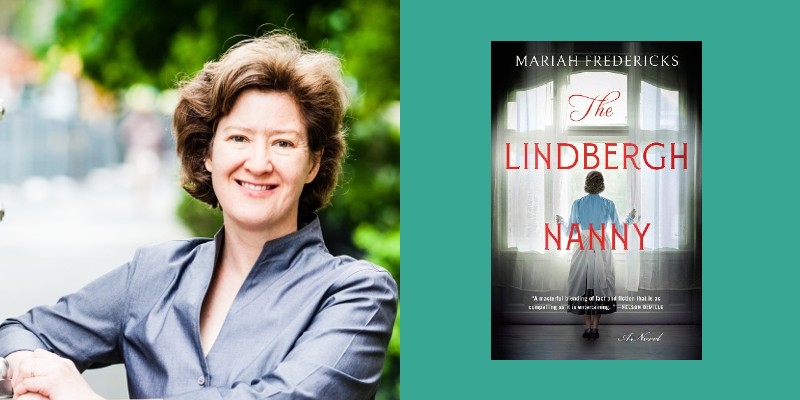

Reality often plays a role in fiction. There are contemporary “ripped from the headlines” stories—these days often with a podcaster as the protagonist— lining the shelves are novels inspired by murders, kidnappings, bank robberies and airplane hijackings among many other bad acts. And then there are historical mysteries peopled by bold faced names of the time. (Teddy Roosevelt makes an appearance in Mariah Fredericks’ Jane Prescott series; Princess Elizabeth collaborates with Maggie Hope in an early installment of Susan Elia MacNeal’s series of World War II mysteries; famous figures from Dwight D. Eisenhower to John F. Kennedy appear in James R. Benn’s Billy Boyle mystery series.) In The Lindbergh Nanny, Mariah weaves a “ripped from the headlines” story rife with bold-face names of the times into a compelling read with a protagonist who was, indeed, the Lindbergh’s nanny at the time of the couple’s first-born son’s abduction. In her recent CrimeReads essay, The Heartbreaking Details of Historical Fiction, Mariah wrote about the ethical obligations necessary to portray such a character without exploitation. It was a delicate dance, one in which Mariah had an instinctive knowledge of the steps. As Mariah wrote, “It’s their pain, not mine. My story, but their lives.”

Mariah’s essay explains the “how” of navigating a crime fiction novel featuring a real person who had a very real role in the events. But I was interested in the “why”?

Nancie Clare: There are a lot of ways into The Lindbergh Nanny, but I think we should start at the beginning. Real historical figures often populate historical novels—including your series featuring Jane Prescott, who is fictional. But Betty Gow—the central figure in The Lindbergh Nanny is different. She was a very real person who played a real role in one of the world’s most infamous cases. And it’s a point of view to what happened—and what led up to the crime’s aftermath—that I think is entirely new. How did you come upon Betty Gow and what about her said to you “I need to tell this story”?

Mariah Fredericks: I had just turned in the first most recent Jane Prescott and of course I started badgering my poor agent: “Do you think they’ll want another? Will they want another, they’ll want another, right?” Covid was hard on series. [The publishers] came back and said, “We’d like you to try a historical standalone.” And I thought, “man, what am I gonna write about that will be so immediately compelling that it doesn’t matter if anybody knows my work or not? Because I write a lady’s maid series. I started swapping in servants to big historical events. I was like, “We could do the violinist on the Titanic, or we could do the chauffeur on Franz Ferdinand’s last ride before the assassination?” And, oh, it’s supposed to be a mystery. There’s really no mystery as to what happened to those poor people.”

Then I remembered Murder on the Orient Express. The 1974 movie starts with a montage of the kidnapping of Little Daisy Armstrong. You see the nanny tied up on the ground. And I remembered that that book had been inspired by the Lindbergh kidnapping. And I thought, “Did they have a nanny? Was she a real person? Was she an appealing person? Was she actually involved in the event or was she a footnote? Did the police interview her to find out what the baby was wearing?”

A quick Google search said “yes,” she was a real person. Her name was Betty Gow. I went to Susan Hertog’s biography of Anne Morrow Lindbergh. She had interviewed Gow for her book, and I discovered that Betty was enormously appealing—sharp witted and she really loved the child. And even better from my point of view, Betty and her boyfriend were prime suspects along with several members of the Morrow and Lindberg staff, because the police believed it was an inside job. I wrote it up in one paragraph and sent it to my agent. It was one of those things: I can’t believe it hadn’t been done before. And obviously in the half hour that I am waiting for them to sign off on it, somebody’s gonna do it. And my agent called me up, she said, “Give them any of the other ideas you thought of.” And I said, “No, this is the idea.” I was down the rabbit hole with life of Betty Gow.

Nancie Clare: Telling the story of the Lindbergh kidnapping from Betty Gow’s perspective does a great job of putting the story in context. Betty was with little Charlie Lindbergh probably more than his parents.

Mariah Fredericks: It’s a pretty good bet. They were away for a lengthy amount of time on their trip to Japan and before they left, they were very busy preparing. Charles and Anne had just recently gotten married, so I think Anne was still way into her husband and he didn’t want her becoming too attached to the baby.

Nancie Clare: That brings up Charles Lindbergh’s idea of child raising that Betty is supposed to practice: the draconian potty training, the idea of not holding him and letting him cry. I know these ideas have sort of ebbed and flowed throughout child rearing forever, but his seemed particularly harsh.

Mariah Fredericks: Yeah, one thing I discovered after I wrote the book was that Charles Lindbergh’s daughter used to joke “Why did he [Charles Lindbergh] make the big flight? To get away from his mother!” Apparently [Lindbergh’s mother] was a bit of a hoverer. So, there was that. And his father was very much a “Hey, let’s throw the kid into the deep end of the pool and see if he sinks” kind of guy. So, some of that [childrearing philosophy], he came by naturally. [Lindbergh] was—to me at this point—a very immature, emotionally stunted guy. He had never dated anybody before. [Anne, his wife] was his first relationship and he was a control freak and was to the end of his life. The trend at that time was that the way mommy ruined the baby was by loving it too much and cuddling it too much [ruining] its self-sufficiency and ability to cope in the real world.

I think for Lindbergh it fit in very nicely with his emotional inclinations anyway. And for Anne, she was somebody who really wanted to do things that would please him. And so, she went along with the method too. There’s a scene in the book where Lindbergh dressed the baby very warmly, placed him in a little pen made of chicken wire in the yard with some of his toys and left him out there for hours. Of course, the poor baby starts crying. And Betty was horribly upset. She went to Anne and she said, ”I have to go to him. I can’t stand it.” And Anne said, “Betty, there is nothing we can do.”

Nancie Clare: One other incident was when he hid his son…My god, did that really happen?

Mariah Fredericks: He did that…

Nancie Clare: Lindbergh took his son out of his crib and hid him? Who does something like that?

Mariah Fredericks: He was a big fan of practical jokes that bordered on cruelty, and he did hide the baby. I’m sure subconsciously it was a reminder to Betty: you’re not to hover over the baby as well as make her feel silly for worrying about the baby.

Nancie Clare: It has, in light of what happened, a chilling sort of prescience.

One of the things I want to explore with you is the phenomenon I call celebrity adjacency or celebrity-by-association. And how the proximity to fame can lead to the delusion that you’re also famous. But in your story of Betty Gow, she does an excellent job of resisting celebrity-by-association. And I think that’s borne out by her actions after Charlie’s body is discovered. She went back to Scotland and rarely spoke about what happened. And I wonder if that was because of her natural Scottish reticence or just Betty Gow being Betty Gow?

Mariah Fredericks: I think that the whole thing, her experience of fame adjacency, was so horrible that she became in the mind of the American public—and some in England too—as the nurse who let something horrible happen to the most beloved baby in America. People thought she was a gangster’s girlfriend or that she had been duped by her boyfriend to help him kidnap the baby. There was nothing great about fame for her. When she came back for the trial, she does have this huge triumph. There’s a certain point in the trial when she stood up for herself with such spirit that the whole place burst into applause. And when she returned to Scotland, it was funny, after the book was finished, I found a lovely little interview with her where they said, “Miss Gow, you had offers from Hollywood?” And she said, “I certainly have, but they are so degrading that no self-respecting Scottish woman would ever dream of doing such a thing.”

Nancie Clare: Denise Mina is gonna love that quote!

Another thing that struck me was for, maybe, the most famous couple in the world they were awfully cavalier in how they hired someone to care for their infant son.

Mariah Fredericks: I’m astonished. They had enormous confidence in their own judgment. And when the crime happened, Lindbergh told the police, “All our people are excellent people. I vetted them myself. I talked to them for an hour!” So obviously they are all beyond reproach. I mean it’s admirable on one level, but I was astonished that a couple that famous and targeted would not be more careful. I guess I was naive.

Nancie Clare: I need to ask you a craft question: You have this fantastic story about a real person who was involved in one of the most infamous crimes of all time. When you were writing, though, how did you decide the right time to step into the speculative; cross the bridge from cold hard facts to that land of speculation— also known as fiction? When did the embroidery start?

Mariah Fredericks: That’s really interesting.

Nancie Clare: You know, you made my day by saying that question was interesting. I live for that.

Mariah Fredericks: The first sort of metaphorical leap I took was that this was gonna be an inside-outside story. It originally started with Betty showing a Lindbergh biographer around her garden, her house. And then I decided not to do that. Then I started with Betty coming up to that house and the description of the structure, because the house and the windows are such a huge part of this story. I’m so used to Jane’s voice (Jane Prescott, the protagonist in Mariah’s series), I’m so comfortable in that voice that for a long time Betty’s voice was serviceable, it was fine it was standard young-woman-historical-novel voice. And then I was working on the scene where she had to identify [the baby’s] body and I had just watched an episode of The Handmaid’s Tale, where they use a Kate Bush song “This Woman’s Work.” And there was something about the image of Betty and that song in that situation that all of a sudden my understanding of her went into hyper drive. And I felt much freer in what I could have her observe what I could have her feel. The range of her emotions and her voice just clicked into a whole another level.

Nancie Clare: It’s a been long time coming, and people more knowledgeable than me will come up with a multitude of examples of how it’s been around for hundreds of years, but the role of women in literature—as protagonists—is changing. Personally, I think it’s a manifestation of a long, long, long simmering fury

Mariah Fredericks: I was thinking about this, and this is truly not to go back to plugging the book, but…

Nancie Clare: Plug the book! Plug the book!

Mariah Fredericks: I was thinking about this with Anne Morrow Lindbergh and the narrative of her after her son’s kidnapping and death, the America First thing, the consideration of moving to Germany is that she’s in shock and she’s depressed and she’s just going along with her husband. Anne Lindbergh was this very passive person. And what I found reading her diaries and her letters, is the level of anger that she had is phenomenal. At one point she tries to go shopping and people just flood her. And she’s so upset and frustrated. And I thought, “why don’t we ever acknowledge that Anne was angry? Why is that not an acceptable part of the narrative? Nobody wants to think that she would’ve been drawn to [her husband’s political views] out of rage. She was very angry at people and [she might have felt that] people have to be controlled and people have to be stomped upon. [That idea of control] might have actually appealed to her at that point. I mean, not to excuse her, but just because we like her, that doesn’t mean she would never get angry.

Nancie Clare: The story of women in literature from ancient times seems to have been you’re either Madea or you’re the Madonna,

Mariah Fredericks: Right

Nancie Clare: Or you’re a prostitute. It’s okay for male characters to be motivated by anger …

Mariah Fredericks: Right? They’re not psychopaths. They are righteously angry or moodily angry or …

Nancie Clare: Self destructively angry or whatever. Does that underlying anger color the work? This acknowledgement that women are good and truly pissed off—and with good reason?

Mariah Fredericks: I think that people are getting more comfortable and more confident about putting women at the center of stories of murder and war and espionage and giving them agency so that they’re not always handmaids to a great man. I think anger is still a tricky thing for us to accept. I think you have to build up a lot of affection for your character before you can have her be nasty or enraged or destructive or angry. I mean, she can be righteously angry, of course, that’s fine. But I think it’s still an issue. I think there are still rules.

Nancie: I’ve spoken to a lot of writers of series who have written standalones or started a new series. You’re invested in Jane Prescott, the protagonist of your series. You have Jane’s voice in your head, you have cast of characters with whom she interacts. But do you think writers of series are well served by writing standalones? Did you find writing The Lindbergh Nanny sort of a palate cleanser? And do you think the break gave you renewed energy for your series?

Mariah Fredericks: I was apprehensive about doing a standalone and I was certainly upset about leaving Jane. But it was a wonderful experience, and it was truly one of those bad news that turns into a really great opportunity because I got to stretch as a writer enormously. My next book is a standalone.

Nancie Clare: Oh, you anticipated my next question.

Mariah Fredericks: Creatively, I think stretching yourself is really great. It’s much easier to break through with standalones. Maybe I’m wrong, but if you haven’t broken out with a series by book four, it’s tough. Not so many people are searching the tables at book stores for book five.

Nancie Clare: What can you tell us about the next book?

Mariah Fredericks: It is in fact done. I have turned it in. I’m continuing with the “novel of True Crimes.” And this one is about—I’m gonna see if you’ve ever heard of this—The murder of David Graham Phillips in 1911?

Nancie Clare: Nope. Sorry.

Mariah Fredericks: You would’ve been the first if you had heard of him. He is a journalist turned novelist and he was very sort of flamboyant and he wore a white suit everywhere and a carnation in his lapel. He was assassinated near Gramercy Park right outside the Princeton Club, which used to be Stanford White’s old home. And the person solving his murder is going to be Edith Wharton.

Nancie Clare: Oh, fabulous.

Mariah Fredericks: It was huge fun to write. She was in New York in 1911 give or take a few months of the murder. And she had had gathered Henry James, her oldest friend, Walter Berry and her lover, Morton Fullerton, to ask them, “Should I leave America? Should I leave my publisher, and should I leave my husband?” So that’s the mood that she is in when this murder takes place!