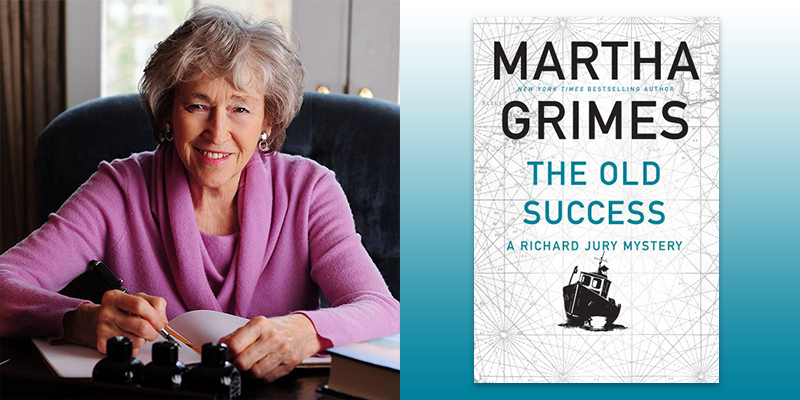

It was a hot Sunday in May when I took a cab from Malice Domestic, a cozy and traditional mystery convention held yearly in Bethesda, Maryland, over to the quiet suburban home of Martha Grimes, the octogenarian author of the cleverly plotted Richard Jury series, where each novel is sprinkled with just the right dashes of humor and character development. Loyal readers line up for each new installment of the series, usually delivered yearly, and each charmingly named after a classic English pub.

Martha Grimes’ works were scattered all about the house as I was growing up. My mother was a fan of English countryside mysteries in general, and the Richard Jury series in particular. The series, each book titled after a (real or imagined) English pub, was a familiar site draped over the arms of chairs. I didn’t become a fan until, bored and unemployed the year after college, I picked one up and then quickly tore my way through each and every one. While the series is anchored by the intelligent and methodical perspective of Scotland Yard detective Richard Jury, it draws its appeal from the charm and foibles of secondary characters, including the lovable Melrose Plant, an aristocrat who’s given up his titles and is forever squabbling with various elderly aunts, the hypochondriac Sergeant Wiggins, and all the quirky denizens of the small town setting.

Grimes’ house, found along a tree-lined street with impressively manicured flower beds, may be located in the DC area, but, like her series, it feels very English. The house is filled with knick-knacks and comfy seating, and there are two fluffy cats that wander in and out during our conversation. After welcoming me into her home, Martha immediately offers me some tea, then proceeds to tell a story about Richard Jury and Melrose Plan arguing over the merits of tea cups versus mugs as we make ourselves comfortable in her parlor/living room. Greeted by the presence of one of her pets, we immediately switch to discussing the joys of having friendly cats. Her cats are only friendly with people—aside from each other, she informs me, they hate other cats. After cooing over her kitties for a while, I get going with the questions.

Up until preparing for my visit to meet Martha Grimes, I had no idea she wasn’t British. I ask her about this, and she reassures me that’s a common misconception. She chose to set her mysteries in England because she liked to read British mysteries, she liked England, and she decided she’d rather set a series in Britain than the United States (I completely agree with the sentiment, although these days, neither’s looking particularly good). Nowadays, Grimes doesn’t read many mysteries, but growing up, although she didn’t like to read much then at all, some of her favorites included Agatha Christie and other British writers.

Up until preparing for my visit to meet Martha Grimes, I had no idea she wasn’t British. I ask her about this, and she reassures me that’s a common misconception. She chose to set her mysteries in England because she liked to read British mysteries, she liked England, and she decided she’d rather set a series in Britain than the United States (I completely agree with the sentiment, although these days, neither’s looking particularly good). Nowadays, Grimes doesn’t read many mysteries, but growing up, although she didn’t like to read much then at all, some of her favorites included Agatha Christie and other British writers.

When she first got into writing, Martha Grimes didn’t start out with the intention of crafting mystery novels. When I ask about her interest in poetry, she tells me that in school, she dated a poet, who was in a poetry workshop. “I said to him, do you think I could get into that? I’ve never written poetry, and he said, oh yeah, sure, just write something, so I did, and I got in.” She enjoyed writing poetry, but found it very difficult. She sees “an enormous difference between writing just fiction and writing poetry.” We begin to discuss if crime fiction had any affinity with poetry—I mention that there are lots of mystery writers who also write poetry; my theory is that in crime writing and poetry, every word has to mean something. Martha doesn’t buy the connection wholeheartedly, but she thinks if there is a connection between the two, it’s that mysteries and poems both have rules (mystery fiction’s adherence to rules is part of the reason she doesn’t much like to read it these days). She prefers the rules in poetry, saying that “poetry is form, and you can’t say that about fiction…It’s the form that inhabits the poem.”

I start talking about how it seems to me that these days, rules in crime fiction are just guidelines; you can use them as jumping off points to take the narratives in lots of new and different directions. She responds that “when it comes to guidelines, there aren’t really, as far as I’m concerned…You need a detective of some form or other, professional, amateur, whatever; you’ve got to have a crime which is serious enough to warrant this whole book [usually murder]; the only guidelines I follow are those. Here is a detective, or two detectives, someone’s been murdered, and they’ve got to figure out why.”

Martha Grimes may be most famous for her mystery novels, but she writes outside the world of crime. Her genre-specific fame is both a blessing and a curse—it bothers her that when she writes books that aren’t mysteries, they tend to only get reviewed as mysteries. Some of her other works contain mysteries within, but “that’s quite different from a book which is driven by a mystery.” She mentions a new series she’s been working on about hitmen and publishing, calling them “a joy to write.” In general, though, she feels trapped in her genre designation, and frustrated with the literary establishment’s failure to accept each of her books entirely on its own.

“When it comes to guidelines, there aren’t really, as far as I’m concerned…Here is a detective, or two detectives, someone’s been murdered, and they’ve got to figure out why.”The exception was her well-received memoir, cowritten in 2013 with her son, Ken Grimes, about their struggle with addiction titled Double Double: A Dual Memoir of Alcoholism. She had the idea for the memoir 10 years before her son agreed—she thought it’d be “interesting to have one person who’s an Alcoholics Anonymous advocate, and another person who wasn’t.” Martha Grimes went to a clinic for her treatment, while her son has recently attended his “3,000 AA meeting.” The clinic, she remembers, wanted her to go to meetings; she tried, even attending meetings while traveling abroad, but never got much out of them. She took issue with the religious feel of the supposedly secular gatherings, but praises AA meetings as the only places she can think of that are “totally non-judgmental.” Her son was intimidated by the process of writing, but Martha believed in his work. One would think such a tell-all memoir would be a revealing experience for all, but Grimes is insistent that there were no surprises, other than learning the truth about a little white lie told by her son regarding a large sum of cash mistakenly given to him by Western Union. She doesn’t plan on writing any more memoirs—she’s got plenty of other things she wants to write first. I tell her it seems like the memoir has meant a lot to a lot of people; she pauses, hesitates, then says, “That’d be nice.”

She’s been writing the Richard Jury series for quite some time. A friend of hers once gave the sage advice that “Once you have characters, all you need is a plot.” She insists, however, that writing mysteries is much more difficult than any of the other stuff she writes, because in a mystery, “you’ve got to do certain things.” General fiction provides much more freedom, as does, well, anything other than a crime novel. She likes to hide Easter eggs in her Jury novels, imbuing them with quirky little details, things she enjoys. Martha Grimes shares a quirkiness with her characters, and in each encounter in Jury’s small hamlet, or each altercation between Melrose Plant and one of his shocked elders, you can feel a bit of Martha’s personality seeping into the traditional village mystery that’s become her bread butter without ever ceasing to be a creative outlet. She likes to gently poke fun at friends and family; a niece’s frequent car accidents provided fodder for a subplot involving a plaster pig and an unfair court decision (The niece legendarily got herself out of an accident-induced pickle by taking the case to court, despite it being clearly her fault, and got off when the officer who reported the accident failed to appear).

In addition to her Richard Jury series, Grimes also writes lots of other fiction, including two books making fun of the publishing industry. People often think they’re based on her own knowledge of Knopf, but Grimes says that’s simply not true. She does acknowledge some creative inspiration from an editor she used to encounter who was far too “spiffy” and formal, and the title of the first, “Foul Matter,” comes from an industry term for original manuscripts that have yet to see an editor’s pen. Martha was so astonished by the phrase that she decided to make a book out of it. She’s worked with a number of different publishers over the years, and each finds its way into her send-offs—she doesn’t have anything against anyone, but she thinks the whole industry can sometimes feel stuck in the Middle Ages; it’s slow to adapt to new technologies and can feel too committed to procedure for flexibility. Rollouts for lead titles look substantially different from the kind of limited support given to most authors. These are not only Martha Grimes’ concerns, and publishing is in a never-ending fight to keep up with tech, bring out quality, in-demand content, and still feel, well, human. (Full disclosure: this website is part of that effort).

I ask her how she’d want publishing to change, and she responds that she’d really have to think about that, but the thing she wants the most is an industry that communicates—with its authors, and with the public at large. She also wants to see an industry dedicated to the truth, no matter how uncomfortable. She finds it ironic that communication should be so difficult, “in this our age of communication.” She looks around and sees a world full of people staring at their phones, none talking to each other. We’re replacing deep thinking with catchphrases, keeping up with Instagram influencers better than our own families. She hates email, and she especially hates opening an email to see the phrase “hope you are well.” She sees it in every email, and no longer trusts the sentiment to be heartfelt. I admit that I send out my fair share of formulaic emails. Martha smiles and says that she treats each email “like a letter.”

She gets a lot of emails from fans, which are always nice. She used to get letters, and she wonders why people don’t write personal letters any more. She especially can’t stand to see a death announcement delivered electronically. People should notify someone of a death more personally. She also wishes more people sent flowers.

I ask her a question I ask all female writers, because I feel like women don’t get asked about craft enough: what’s her advice to aspiring mystery writers? Her advice to writers is the same as her general advice in life: never, ever, ever, ever, give up. Grimes’ take on writing feels a bit like Douglas Adams teaching us how to fly: just start writing, and then, don’t stop. The trick to flying is to fall, and never hit the ground.

Grimes also urges us to never let style go by the wayside—twists and turns mean nothing if the words themselves lack power. Her favorite works are driven by style, not plot; she doesn’t think style can be learned—“If you have it, you have it, and if you don’t, you don’t.” And both Martha Grimes and her characters have plenty of style.