Late in the morning of June 21, 1947, Mary Roberts Rinehart sat in the library, speaking to her butler. She had hired him earlier that summer and hoped he would suit, unlike the other butlers who had come and gone. Eaglesgate was a lot of ground to cover—literally, what with the hilltop manse, the guest houses dotting the carriage roads, and the long way down to Eden Street, one of the main streets of Bar Harbor, Maine. But an able butler could do it.

Rinehart had purchased the sumptuous, seven-acre estate, then known as Farview, ten years before. She’d rented in Bar Harbor for two successive years, falling ever more in love with the island resort town by Frenchman Bay. When Rinehart learned the estate was for sale at an absurdly low price—this was the height of the Great Depression—she pounced. Rinehart was not born rich, but the success of her novels, plays, and stories, beginning with The Circular Staircase (1908), catapulted her several rungs up the economic ladder. She could afford several houses, and to employ several servants.

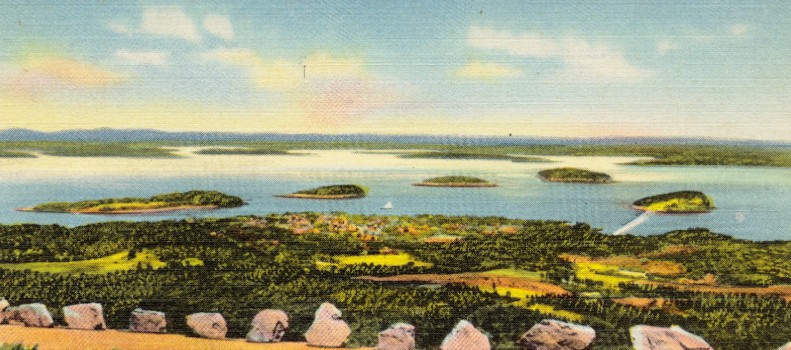

Frenchman’s Bay, Bar Harbor, Maine, circa 1947.

Frenchman’s Bay, Bar Harbor, Maine, circa 1947.

Her husband, Stanley, had been gone for five years, spurring her to relocate from a gigantic apartment in Washington to one on Park Avenue in New York City, and to give up another home in Wyoming because the mountain air worsened her heart condition, and she could no longer climb stairs as well as before. Her three sons were grown, and the eldest and youngest, Stanley Jr. and Ted, had become her publishers since co-founding Farrar & Rinehart in 1929. A new house could not assuage lingering grief and loneliness, but a new place to entertain guests for elaborate summertime parties could act as balm. And for the next decade, Eaglesgate was that balm.

At nearly seventy-one, Rinehart was closer to death than to her peak, but she was still regarded as the Grande Dame of American mystery fiction, even as the current genre kings & queens gravitated towards the harder-boiled, and to more realistic depictions of life and of people. When she published, her books sold, and sold well, most recently The Yellow Room (1945), a patented concoction of murder, mystery, suspense and romance set in a town distinctly resembling Bar Harbor.

Rinehart was also about to reveal in the July 1947 issue of Ladies Home Journal that she had been diagnosed with breast cancer in 1936, the second year she rented in Bar Harbor, and had undergone a successful mastectomy. “It wasn’t easy to write this story,” she told an interviewer, “but one out of every three cancer deaths is needless…could I continue to be silent?” For that interviewer, Gretta Palmer, it was important to depict Rinehart as “a woman whose abounding vitality is a contagion to all who visit her” and to “realize that she is alive as anyone that you will ever know.”

Cancer didn’t kill Mary Roberts Rinehart, though it came close. Then death tried to come for the famed mystery writer again in Bar Harbor.

* * *

Blas Reyes had had enough. He was quitting, and this time he meant it. He had tried to several times before, but Mrs. Rinehart never took his declarations terribly seriously. He would fulminate, she would give an anodyne platitude, and the next morning, Reyes would be right where he was supposed to be—in the kitchen, responsible for the generally excellent meals served to Mrs. Rinehart and her guests.

Reyes joined the Rinehart household in 1922, after Dr. and Mrs. Rinehart relocated to Washington from Glen Osborne, Pennsylvania for the doctor’s new job with the Veterans Administration. Reyes was previously employed as a butler by an Army general living in the Adams Morgan neighborhood, and when the Rineharts hired him, he took on that position, as well as head chef.

The life of the Rineharts was several strata removed from the life of Blas Reyes. In 1907, at the age of twenty-four, he had emigrated from the Philippines to San Francisco. Reyes was among the first of a large wave of Filipinos arriving on American soil after a new immigration law, passed earlier that year, loosened the heinous restrictions of the quarter-century-old Chinese Exclusion Act.

From San Francisco Reyes made his way to Washington, where by 1910 he worked for a man named Albert Whelan, residing with his wife and sister-in-law in Georgetown. Records don’t indicate when Reyes stopped working for the Whelans and started with the Army general, but it seems to coincide with the start and end of his marriage to Ada Smallwood, also a servant, with whom he had a son, James Blas Reyes, in 1913.

Working for the Rineharts altered Reyes’s life even more. He met his second wife, Margaret Cody—always Peggy—when the Irishwoman was hired as a maid by Dr. and Mrs. Rinehart in 1926. His confidence increased with every compliment he received for the meals he prepared for holiday dinners. One Christmas Eve, the menu Reyes prepared, including a dish of sweet potatoes and marshmallows, was so well-received by the Rinehart guests that Reyes came in to a champagne toast, bowing to accept his congratulations.

But Reyes always felt that Stanley Rinehart, the doctor, was his employer. He felt more ill at ease with Mrs. Rinehart, with taking orders from a woman. But after Dr. Rinehart’s death in 1932, there was no way Reyes could move back the clock. Peggy certainly did not want to leave. Yet Reyes felt restless, which emerged in his habitual need to resign his post. This carried on for a decade and a half.

Now there was a new butler at Eaglesgate. Reyes was no longer the highest-ranking servant. He was sixty-four. He had worked for both or one Rinehart for a quarter of a century. He was tired. He was old. He complained that he wanted to go home. He had worked through World War II, when anti-Asian sentiment was at high pitch. The new butler was the last straw.

Blas Reyes resigned one more time on June 20, 1947. This time, Mrs. Rinehart did not wave away his declamation. This shocked Reyes. He went back to his quarters and told Peggy they had to leave Eaglesgate immediately. Peggy refused. This was her home, and she had no quarrel with Mrs. Rinehart. Reyes started drinking and kept at it. A disagreement devolved into a fight.

There was no resolution the next morning. Reyes’ resignation would stand, and Peggy did not want to go. She could not stop crying. Even when Mrs. Rinehart discovered her and asked what was the matter, Peggy’s tears didn’t stop. It hurt to explain to her employer what was happening, that she’d fought with her husband, that he was prepared to leave the premises, but she would not. Mrs. Rinehart seemed taken aback. She thought his declamations had been like all the other ones, and that Reyes would resume his post.

Many would say, later, that Blas Reyes could not have been in his right mind. Perhaps that was so. It could explain the inexplicable, account for the unaccountable. Had Mary Roberts Rinehart known what was in the heart of her longtime chef and sometime butler, would she have been in the library on the morning of June 21, 1947?

* * *

Just before lunch, Mary Roberts Rinehart was still in the library, finishing her conversation with the butler. Then she heard a voice she recognized.

“Get out,” said the man.

Rinehart looked up. Blas Reyes, her chef, the one whose resignation she had heard out the evening before, stood at the library doorway. He was in shirtsleeves, a button loosened near the neck.

“Where is your coat?” asked Rinehart coolly.

Reyes moved towards Rinehart, closing the distance between them. When he was five feet away, he pulled something out of his hip pocket.

“Right here.”

Reyes held a pistol in his hand. Rinehart began to fathom what was about to happen. Reyes pulled the trigger.

In that moment, Rinehart expected to die. But she didn’t. The pistol didn’t work. The bullets were too old.

Rinehart ran towards the kitchen. Reyes ran towards her, and she pushed him away. The butler ran down one of the carriage roads all the way to Eden Street to get help. He thought Reyes meant to kill him, not his employer.

On her way to the pantry, intent on calling the police, Rinehart was momentarily distracted. A young man stood outside the main door. Rinehart asked why he was there. He said he was looking for a job as a gardener’s assistant.

“Young man,” said Rinehart, “You’ll have to come back later. There is a man here trying to kill me.” The boy left, never to return.

Both Rinehart’s personal maid, Margaret Muckian, and her chauffeur, Ted Falkenstrom, witnessed Reyes attempting to kill their employer. Falkenstrom tackled Reyes and took away the pistol, throwing it over a garden wall. Muckian ran to the kitchen to attend to Rinehart and bring her the nitroglycerin pill she was supposed to take at that hour.

“Young man,” said Rinehart, “You’ll have to come back later. There is a man here trying to kill me.”Rinehart went to the phone. Reyes broke free from Falkenstrom and went into the kitchen. He emerged with a long carving knife in each hand and came up behind Rinehart. Before he could stab his now-former employer, Falkenstrom and the gardener ran in and once more, knocked Reyes down to the ground. Muckian sat on Reyes’s chest, while Falkenstrom continued to pin Reyes, taking defense wounds on his arms from the knife slashes. The chauffeur and the maid managed to keep the chef in place until police arrived in the library.

This was the most exciting event to happen in Bar Harbor in recent memory. The town police captain, Howard MacFarland, arrived on the scene. As Reyes was led away by officers, MacFarland asked Rinehart, safe but shaken up, what had happened.

“I can’t think what caused the attack,” she said.

At the station, Blas Reyes was questioned. According to the chief of police, George Abbott, Reyes signed a confession saying that he felt discouraged and “wanted to go back home.” Abbott later told reporters: “We have to attribute the entire episode to insanity. Though the chef made a full confession, he was unable to give or refused to give any coherent motive.”

The next morning, patrolman Alfred Reed made his rounds to the jail cell. He found Blas Reyes dead, hanging from a noose fashioned from his clothing.

* * *

Mary Roberts Rinehart learned the news of Blas Reyes’s suicide from her middle son, Alan. He’d flown up from New York to be with his mother upon hearing of her near-murder. Rinehart was still stunned by the turn of events, and how close a call she’d had. Now Reyes, her longtime chef, had killed himself. There was nothing to celebrate, and so much to lament. Peggy was now a widow. James, once he learned of the news, lost a father.

Rinehart felt no anger, only sadness. She paid for Reyes’s funeral at Holy Redeemer Church. She insisted he be buried at the church’s cemetery a few miles outside of Bar Harbor. The priest acquiesced, mindful that Reyes was “plainly of unsound mind.”

The chef’s suicide cast a dark and foreboding note. For this was to be Mary Roberts Rinehart’s final summer at Eaglesgate. Four months later, on October 24, 1947, forest fires in Acadia National Park engulfed nearly all of Bar Harbor, as well as other nearby towns in Mount Desert Island. The flames destroyed more 17,000 acres and nearly 200 houses, among them Eaglesgate.

No one was in residence, for Rinehart had returned to New York for the winter, putting the final touches on her next novel, A Light In the Window. But the loss of Blas Reyes would be forever linked to the loss of her beloved home. “[Reyes] hanged himself in the local jail that night, and perhaps it was the best way out,” Rinehart later wrote of her terrifying ordeal. “But he had loved and been proud of the house, and now both he and it were gone.”

* * *

Eaglesgate burned, but remnants remain, and from those lingering cobblestone steps and walls emerged something new. The Wonder View Inn opened for business a few years after Mary Roberts Rinehart’s death in 1958. I stayed there over a mid-August weekend, thinking I might better understand what happened on the morning of June 21, 1947 by being physically present at the location.

Most of my understanding, though, came from books or newspaper accounts of the near-murder. I read Jan Cohn’s excellent biography, Improbable Fiction: The Life of Mary Roberts Rinehart (1980) while in my hilltop room overlooking Frenchman Bay, drinking blueberry sodas at local restaurants in downtown Bar Harbor, or sitting on the Island Explorer buses that shuttle people around Mount Desert Island, for free.

It was strange and more than a little thrilling to read about Rinehart in the summer place she so loved, but clearly did not love back to satisfaction. Bar Harbor gave its all the weekend I was there, with brilliant cloud-dotted blue skies, energetic fiddle players playing tunes at Irish pubs, and the lavishly gorgeous, and mildly treacherous, Acadia National Park. It was a tourist trap, but so what. I ate it all up, including the decadent desserts.

Being in Bar Harbor was more vacation than work, but thoughts about Blas Reyes would always intrude. How did he contend, so many decades ago, with this onetime playground for rich Northerners and bohemian-styling artists and writers? Did the inequality, or the possible racism, grow too wearying, until it crested into violence? Did he and Peggy visit the National Park or go into town for respite by the water?

Rinehart felt no anger, only sadness. She paid for Reyes’s funeral at Holy Redeemer Church. She insisted he be buried at the church’s cemetery a few miles outside of Bar Harbor.I wanted to know, but newspaper accounts could not tell me. Looking for his grave at Holy Redeemer Cemetery couldn’t tell me. Searching fruitlessly for descendants couldn’t tell me, either. I had facts, but I would have to imagine the emotions and the psychology of a man desperate enough to attempt to kill his employer, and, failing to do so, kill himself as a means of expiating his perceived sins.

And I wondered, too, about Rinehart. She had faced sober reality in life so often, first as a nurse, then as a correspondent during World War I, and then through the usual losses a person experiences when married with children. But she shied away from realism in fiction and thought little of the Sherwood Andersons, the F. Scott Fitzgeralds, and the Upton Sinclairs of the world. Their brand of fiction prevailed. Hers fell out of fashion.

Rinehart tried hard to stay rooted to her girlhood of moderate means. In an interview she gave to the New York Times Book Review in 1940, she conveyed ambivalence about her grand lifestyle and unlimited luxuries because “a storyteller needed conflict: without change, the writer must reach far back for material.” But she never understood why she could work her way up the success ladder and scores of Americans could not.

When Blas Reyes pulled out his pistol, did Rinehart understand the gulf between master and servant, or was it forever beyond her comprehension? No doubt she was relieved to live, having survived earlier calamities like the war, the death of her husband, and breast cancer. But Blas Reyes’s choice to die that night was no relief at all.