Long before American television was saturated with CSI and Forensic Files, I was living my own weekly CSI adventure with my family in northern Michigan. My father was a medical examiner for three counties and my mother assisted as his office manager. They ran the office out of our home because the county was underfunded and did not provide him with one.

Dad performed autopsies at the small county hospital morgue, but all the records, paperwork, and photographs were kept in our family office. Samples of blood and body tissue were stored in a basement freezer, right under the pork chops and frozen beans like some B-rated horror flick. Dinnertime conversations often revolved around the case of the week. “Let me tell you about an interesting suicide I saw today,” my dad would say. “Oh, and pass the corn, please.”

During the years Dad worked in forensics, I had a hands-on, front row education in death investigation. It was as natural as brushing my teeth.

One Sunday after church when I was eight, my father toted us all over to the local airstrip. A small plane had crashed the night before and Dad wanted to return to the scene in daylight to scour the area for any remaining body pieces. My younger sister and I paired up to help him. Outfitted in our Sunday best, we roamed the damp field that early spring morning in search of brain matter and skullcap. And yes, we found some. Once I reached pre-adolescence, I was painfully aware how different my family was from other families. I felt the need to hide what my father did. We were living in a generation before TV glamorized forensics. I didn’t know a single other person my age whose father kept body bags in his truck and smelled like formaldehyde. Dad’s work was one more reason my peers might reject me. Ironically, my friends found the family business intriguing and to this day, I can’t remember a single time I was teased about what my father did for a living. (At least not in front of my back.)

We were living in a generation before TV glamorized forensics. I didn’t know a single other person my age whose father kept body bags in his truck and smelled like formaldehyde.One of the first times I remember my home life intersecting with my social life was third grade. A new friend came over to play in our fort in the barn loft and soon became intrigued by a 55-gallon barrel. She wanted to take a look inside, despite my strong discouragement. Eventually, she weaseled the truth out of me. I told her, “There’s a man’s leg in that barrel.” It thrilled her. I cowered as she peeled back that plastic and cross section of thigh stared back at both of us.

Over time, I embraced my unconventional childhood. In fact, I feel quite blessed to have had Quincy M.E. (throwback to a popular ‘80s TV show!) for a father and a doting, self-confident mother who put up with his homegrown experiments in forensic science. (Mom surely must have foreshadowed their future on their first date when Dad took her to see his cadaver in medical school.)

When I started writing I began to tap into my past and discovered that I was drawn to crime stories—from Hitchcock to Fargo to Bones to Mindhunter. Writing crime challenged me in ways others genres could not. For the first time in my life, I felt deeply connected to my past. And I wanted more! I wanted to know everything. I hounded Dad and Mom with phone calls, e-mails, and questions. I devoured forensic books, articles, blogs, and podcasts! Mine was a literary bloodlust. To satiate it, I attended the Forensic Science Academy. From this experience my non-fiction book, Forensic Speak, was born and continues to be used by writers, professors, and law enforcement alike. I began speaking about forensics to empower other storytellers with the treasure trove of experiences and knowledge from those decades of death investigation in my family’s home.

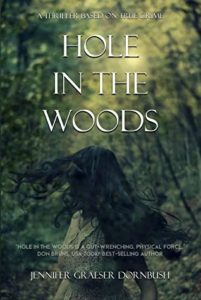

I kept writing, studying, and drawing from my past. My mystery series, The Coroner and Secret Remains are one result of that. And my most recently released thriller, Hole in the Woods , is a direct intersection of my childhood merging with my writing career. Hole in the Woods , is inspired by a murder case my father investigated. This was the case of Shannon Siders of Newaygo, Michigan. Shannon was brutally raped and murdered the summer of 1989 and her body was left for three months at the Hole in the Woods, a local party spot deep in the Manistee National Forest. The case went cold for 25 years. I followed her case from its beginning until the killers went to trial in 2015. Shannon’s story not only lay the groundwork for my fictional version, but also spurred my deeper interest in partnering with the Cold Case Foundation, a non-profit focused on solving the hardest, most forgotten violent crime and missing persons cases. A percent of the sales of Hole in the Woods will be donated to the CCF.

***