Michael grew up on the Jersey Shore, earned a degree in music from Princeton University, and played the drums professionally for a number of years before focusing on fiction writing. He earned an M.F.A. from Ohio State and a Ph.D from the University of Missouri, and for 15 years he co-directed the creative writing program at Mississippi State University, where he was awarded the John Grisham Master Teacher award, the university's highest teaching honor. He currently lives with his family in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

I’m kicking back on a Saturday afternoon, the seagulls singing C-sharp, when a shadow falls across my face and a voice I haven’t heard for twelve years says my name—“Mo”—followed by advice I didn’t ask for. “You gotta start wearing sunscreen.”

Sure enough, there stands Johnny Clay, blotting out the sun. I can see right away that Florida’s taken it easy on him. He appears fit and relaxed in khaki pants, yellow golf shirt, and leather sandals. His hair is stylish, salt and pepper coexisting. He looks like what he’s become: a successful real-estate agent. A man who left Jersey, hung up his guitar, and never looked back.

“What are you doing here?” I ask.

His answer is an expression I used to know well: half smile, half squint, with a flash of frontman intensity—like he knows a secret or maybe all the secrets. “I missed you too, buddy,” he says, and steps over to the metal shed where I rent out chairs and umbrellas by the day or week. Comes out with a chair, unfolds it, and lowers himself beside me. “God, Mo, can you believe they’re actually gonna tear the place down?”

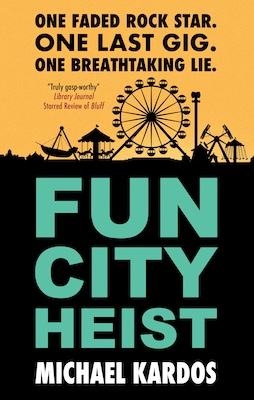

He glances up toward the boardwalk. Toward Fun City. It’s where we all went as kids, same as our parents and their parents before them. For decades, the small beachfront amusement park never changed, which was the point. Hell, there’s still a U-boat ride. But the eighty-eight-year-old owner of the family operation died over the winter, and it didn’t take long for his grown children to decide that beachfront property has gotten too valuable for honky-tonk nonsense. At the end of the summer, they’re tearing it all down and putting up condos.

“Come on,” I say, “you know you’d do the same.”

“Wrong,” Johnny says. “I’d keep it going forever. See, that’s what I’m talking about. How at the end of the day, what matters—”

“Hang on,” I say. Near us, a guy and a girl, both tan and beautiful, are lying on a blanket, the radio between them suddenly blaring. I go over and tell them, “You’re gonna have to turn that down. There’s a noise ordinance.”

“A what?” the guy says.

Shouldn’t be my problem—I didn’t even rent them anything. But for reasons I never understood, this has always been part of the job. Like it’s too lowly for the beach cops and too confrontational for the lifeguards. “You can leave the music on. Just turn it down, OK?”

The girl has propped herself up on an elbow. “No, it’s not OK. And what do you care?”

I feel Johnny watching from his chair, quietly marking a minus in some cosmic scorecard. But no—he’s come up beside me, and slings an arm over my shoulder. “My friend here, he’s being kind to you. I mean, ‘Kokomo’?” He shakes his head. “It’s an affront to music and beachgoing. Mo should kick you off the beach. He really should.”

The couple is watching me, having decided Johnny is insane. “There’s a noise ordinance,” I repeat.

The guy on the blanket shakes his head and mutters under his breath before lowering the volume.

Johnny and I return to our chairs. I expect some veiled or unveiled critique of my existence, or at least of my expanding gut. But Johnny always had a way of saying the thing you least expected.

“I booked us a gig.”

“What are you talking about?” I ask.

“Fun City,” he says. “July Fourth.”

“Who?”

“Who?” He exaggerates looking around, like maybe there’s some other pair of former musicians lurking nearby. “Us. Sunshine Apocalypse.”

We played our first-ever paid gig at Fun City when we were sixteen. We played early on a weeknight for a hundred bucks. We never felt more like rock stars, even after we became rock stars. But we haven’t been rock stars for ages, and now he’s making me state the obvious. “We don’t . . .”—I search for the word—“exist.”

“We’ll reunite for one show,” Johnny says. “It’ll be like old times.”

But old times is hardly a selling point. “Newsflash,” I tell him. “I don’t even play the drums anymore.”

“Um, newsflash,” he says, “it’s the drums. It’s not like it was ever that hard.”

He’s trying to banter like we’re longtime pals. But we were never pals. For a long time, we were much closer than that, childhood best friends who’d started a band, and then we were at each other’s throats, and then he left me and the other guys and betrayed us all.

“Ricky’s already on board,” Johnny says.

“Ricky needs a therapist.” Our lead guitarist never could shake his kid-brother role, desperate to please his three older bandmates.

A seagull flies past screaming B-natural. I don’t seek it out—the note’s just there, announcing itself. But a drummer with perfect pitch is like a blue whale who can count cards.

“Ed’s on board, too,” Johnny says.

“He told you that?”

“Which means that you, Mo Melnick, are the last piece of the puzzle.”

None of this makes sense. For twelve years, not a peep from the man. Now, suddenly, he flies back to Jersey to personally recruit the three of us for a show? There’s something I’m missing, and I don’t know what it is, but I know what it feels like when someone’s working an angle.

“Look, if this is some midlife crisis, I can sympathize,” I tell him. “But there’s no puzzle. No pieces.”

“Yeah, but—”

“There’s no band, Johnny. Do you see a band? Because I don’t.” I take a breath and tell myself not to get worked up over ancient history. You get paid to sit on the beach and relax, I remind myself. So relax. “All I’m saying is, you made your decision a long time ago. I’m making mine now. Thanks for asking. Really. You look great. I hope you’re great. I do. But no band,” I tell him. “No gigs. Not for me. I’ve been done with all that a long time.”

“Huh.” Johnny looks distracted suddenly, like he didn’t hear a word I said. “Hey, Mo?” he says.

“What?”

“I think that woman’s drowning.” He points to a lone swimmer, head bobbing in the waves.

When you live at the water your whole life, you know what to look for. It isn’t big splashing or waving or calling for help. You can do those things, you aren’t drowning. Drowning doesn’t look like drowning. It’s quiet and not obvious.

I glance over at the lifeguard, one of several interchangeable blond teenagers with mirrored shades and a smear of zinc oxide on his nose—but he’s flirting up some girl in a bikini and paying no attention.

We run to the water.

__________________________________