Why do so many journalists turn to writing fiction? The list is legion. Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, Tom Wolfe, Bram Stoker, H.G Wells, Joan Didion, George Orwell, Geraldine Brooks, Margaret Mitchell, Susan Sontag, and countless others.

Perhaps I should narrow down the question. Why do many journalists embark on a life of crime? I speak from experience. I began my writing career at the age of seventeen, as a cadet reporter on an afternoon newspaper in Sydney, Australia. It was a typical tabloid ‘red top’ with bold and breathless headlines, full of clickbait stories before ‘clickbait’ was even a word.

The Sun was sold at newsstands and on street corners by newspaper boys, who yelled out, ‘Extra! Extra! Read all about it!’ handing out papers to passing commuters, heading home from work for the day.

The pages were full police stories court reports. Crime and punishment. The bread and butter of afternoon newspapers. I spent five years working for The Sun, covering arson, accidents, homicides, robberies, kidnappings, prison breaks, natural disasters and missing children. Every day offered a glimpse into the dark underbelly of Australia’s sin city.

I witnessed my first autopsy at the age of eighteen, shown through the state morgue by the Chief Coroner, who warned me not to have breakfast beforehand. This wasn’t my first glimpse of a dead body. I had seen dozens by then – people who had taken their own lives or been the victims of terrible crimes.

For eleven months I worked the graveyard shift – from ten until six – responding to police, fire brigade and ambulance callouts. In our newspaper office we had a radio room, where an entire wall was covered in speakers each tuned to a different emergency frequency.

A copyboy or copygirl was responsible for monitoring the radios, but we all kept one ear on the constant crackle and buzz of call-signs, locations and cars responding. I knew which code meant an officer in trouble, or a domestic dispute, or a weapon offence, and which area of the city it came from. When certain radios fell silent, it meant a special operation was underway. By process of elimination, we worked out the area and raced the scene, hoping to be nearby when the bust went down.

At other times, we were tipped off by friendly detectives. These ‘contacts’ weren’t so much on the payroll as the beneficiaries of beer and expense account hospitality. Ours was a symbiotic friendship – we needed the stories and they wanted positive coverage.

In those first years on the job, I saw outrageous acts of violence and bravery. I was also threatened, beaten up, arrested, abused, and chased down the street by a man wielding an axe. I befriended Australia’s most wanted man, a convicted killer, who was on the run for nearly two years. He would call me at the office, bragging how the police would never catch him, and complaining about being ‘fitted up.’

I still write about crime today, but I no longer chase ambulances and police cars. My psychological thrillers are fictional, but all of them are seeded in fact. My knowledge of criminal psychology and police investigations comes from fourteen years as a journalist and ten years as a ghost writer.

Michael Connelly, one of the world’s most successful crime writers began his writing life as a police reporter on the Daytona Beach News Journal. Later moved south to the larger Fort Lauderdale News and Sun-Sentinel, where he spent six years covering Florida’s drug wars. By the time Connelly, arrived was hired by the Los Angeles Times, he was already dabbling in writing detective fiction.

He did his research, talking to a hundred detectives a week, visiting police stations, befriending detectives, discovering their hopes and fears. His character, Harry Bosch emerged from his hard work – a man whose mantra became, ‘Everybody counts or nobody counts.’

Another celebrated American crime writer, Laura Lippman, spent twenty years as a reporter, twelve of them for the Baltimore Sun. Is it little wonder she made her main character, Tess Monaghan, a journalist? Laura wanted to be a fiction writer from a young age but didn’t know how anyone became a novelist.

‘I had no interest in villains,’ she says. ‘I didn’t want to write about people who are bigger than life…I wanted to write about real people. This is where fiction does something journalism could never do.’

Among Laura’s colleagues on the Baltimore Sun, was columnist Dan Fesperman, now a wonderful writer of espionage thrillers. And Laura went on to marry, David Simon, from the city desk of the paper, who became the celebrated screenwriter and producer of The Wire among other award-winning TV crime dramas.

Over the years, I have shared stages and admired the work of many journalists turned crime writers. Val McDermid, the queen of Scottish crime, spent a decade working as a reporter for The Daily Record and its sister paper The People before turning to fiction. Her latest novel, 1989, is full of autobiographical details from those years, as her main character, Allie Burns, reports on real-life events such as the Lockerbie bombing and the fatal human crush at Hillsborough football stadium.

Linwood Barclay was a celebrated columnist for the Toronto Star before No Time to Say Goodbye became an international sensation. Fiona Barton was the senior reporter for UK’s Mail on Sunday. Robert Harris worked for the BBC and the Sunday Times before Fatherland turned him into a household name.

I could also mention Carl Hiaasen, Stieg Larsson, Jo Nesbø, Jane Harper, Chris Hammer, Peter Temple, Jeffery Deaver and Peter Corris, but I’ll stop before I exhaust myself.

I can’t speak for these other writers, but journalism was a stepping-stone for me. I had grown up in small idyllic country towns and I felt as though I had nothing to write about. Journalism solved that problem. It took me around the world, where I reported on the fall of the Berlin Wall, the break-up of the Soviet Union and the release of Nelson Mandela.

I gathered material and learned that fiction can tell a greater truth than any number of feature articles in a newspaper. Fiction doesn’t impose boundaries or rules. It can be more honest, because the writers can say what they think and feel rather than being limited to what they hear and see.

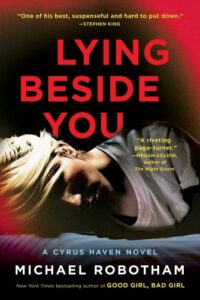

All of my novels, including my latest Lying Beside You, have been seeded in real life events. I use the truth as a framework. I set my stories in actual places. I walk the streets. I sit in the cafes. I beg and borrow and steal descriptions and one-liners and half-baked ideas. But mostly I question everything. That’s what reporters do.

***