Milwaukee, Wisconsin

February 2019

A few years ago, an ad campaign featured Wisconsin native Willem Dafoe sitting in a Greyhound station, in front of him two buses: one departing for New York, the other for Milwaukee. His destiny hanging in the balance, he tells us: “Life boils down to a series of choices. Before long, the choices you make and the ones you don’t become you.”

Dafoe’s vampiric, underfed gremlin face is transposed on a regretful, hardworking wrinkled old man cleaning up after circus animals, while overhead his confident, athletic composite swings on the trapeze. The voice-over is damning.

“Whether you’re good enough, strong enough. All choices lead you somewhere.” Be that a CEO flying in on a private plane, a bored, pencil-pushing shop foreman, a chess champion outthinking his opponent, or a sumo wrestler. It’s a minute and a half doubling down on an infamous throwaway joke Dafoe made about himself and Houdini. Both shared the same hometown, and their greatest escape was leaving Wisconsin.

Poking fun at the stoic simplemindedness, the gleeful love Midwesterners have for low-paying, blue-collar existences because we’re too practical to make bold choices. Dafoe’s ad presents the problem facing Midwesterners: how do you move into the future and hold onto what you love about the past?

When you grow up in or around the city once known as “The Machine Shop of the World,” the expectation isn’t that you’d have the wherewithal for creative pursuits. I didn’t grow up knowing any writers. Teachers, machinists, insurance salesmen, store clerks, office workers, greenkeepers, civil servants; but not writers. People did that somewhere else. Our stories weren’t important enough. We were too bland. Few books take place in Milwaukee, and from the time I could read I gravitated toward any faint mention of Milwaukee or Wisconsin in pop culture. Turns out Milwaukee has more of a literary legacy than imagined.

Robert Bloch’s family moved here from Chicago in 1929, and he lived here until 1953. An avid reader at a young age, Bloch bought copies of Weird Tales from local tobacco and magazine stores with his hard-won allowance. He fell in love with the pulp and wrote a fan letter to H.P. Lovecraft, with whom he struck up a regular correspondence. Lovecraft encouraged Bloch to write and introduced him to a circle of pulp authors who would go on to shape contemporary fiction. Bloch lived on Brady Street above Glorioso’s deli during that time. He began publishing regularly and worked writing ad copy until he got a job as a speechwriter for future mayor Carl Zeidler’s campaign. It wasn’t until he and his wife moved from the city to a small northwestern Wisconsin town that he wrote Psycho, inspired by events in nearby Plainfield.

Fredric Brown worked as a proofreader and typesetter for the Milwaukee Journal. Among his odd jobs, Brown copy-edited pulp magazines, which led him to submit his work because in his mind, he couldn’t do any worse than what he was editing. A heavy drinker, his career grew slowly as he ground out science fiction and mystery paperbacks to keep the bill collectors at bay.

Before he became a major force in publishing and entwined himself in pop culture, Robert Beck, better known as Iceberg Slim, grew up here. Disturbing reverberations of the themes in Beck’s work can still be felt in Milwaukee today, as it’s known nationally as a major hub for sex trafficking. While here, he became enamored with street life despite his mother’s efforts to educate and raise him in a middle-class lifestyle. Beck’s writing career didn’t start until after a stint in jail, but years of hustling on the streets of Milwaukee and in much of the Rust Belt provided the backdrop for his books.

One of the authors who was a gateway into crime fiction for me was John D. MacDonald, the prolific detective story and thriller writer who died in St. Mary’s Hospital. He came here for a heart bypass surgery and is buried in Holy Cross Cemetery. A legendary writer who didn’t reside here while alive, but now spends eternity in the glacial clay soil of Milwaukee, coincidentally in the same cemetery as Dolores Biemann, my grandmother—a woman who appreciated great crime fiction.

Milwaukee is also the hometown of crime writer and Academy Award winner John Ridley, as well as crime/horror legend Peter Straub, whose formative years here left such a deep impact that they continue to haunt his work. Millhaven, Straub’s stand-in for Milwaukee, is the kind of place where a character wonders, What happened to the Millhaven where a guy could go out for a beer an’ bratwurst without stumbling over a severed head?

Straub’s industrial city rampant with crime proved the inspirational fodder for Nick Cave’s song “Do You Love Me? (Part 2)” and more directly “The Curse of Millhaven.”

And it’s small and it’s mean and it’s cold

But if you come around just as the sun goes down

You can watch the whole thing turn to gold . . .

That’s as accurate a description as you’re likely to find. Milwaukee, like so many cities in the Rust Belt, built its identity as a home to manufacturers, a growing immigrant community, and booze. Over the last half-century, as jobs disappeared so did the dreams that came with them. The chance to make an honest living eroded the blue-collar families’ quest for upward mobility.

Milwaukee, like so many cities in the Rust Belt, built its identity as a home to manufacturers, a growing immigrant community, and booze.Presently, Milwaukee is going through a renaissance—abandoned factories being converted to condos, craft breweries and distilleries pushing out corner taverns—yet at the same time it is among the most segregated and impoverished big cities in the country. The gentrification of neighborhoods outside of downtown bear the impact of twentieth-century redlining efforts, forcing residents out due to housing demand, adding fuel to the affordable-housing crisis. Such an environment and atmosphere make excellent fodder for noir fiction—an outlook out of step with the romanticized nostalgia that Happy Days and Laverne & Shirley created of Milwaukee.

Near the end of Willem Dafoe’s ad, he boards a bus headed for New York. “Bold choices take you where you need to be.” In a recent interview, Dafoe explained that the path he took led him to Milwaukee, where he studied and performed with other passionate, supportive performers. Living in Milwaukee exposed him to diversity and different social classes outside of his experience. It lit a fire in him.

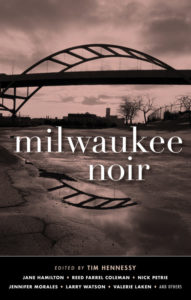

[Milwaukee Noir] is the first of its kind—a short fiction collection about Milwaukee, by writers who’ve experienced life here. The crime/noir genre at its best can be one of the purest forms of social commentary. I’ve gathered contributors who can tell not just a fine story, but who can write about the struggles and resilience of the people who live here. Maybe you picked up this book because you recognized an author’s name, like Jane Hamilton or Reed Farrel Coleman. You’ll also find Matthew J. Prigge and Jennifer Morales, among others, whose stories you won’t soon forget. Or maybe you were intrigued by the word Milwaukee in the title. Whatever the reason, I’m honored to compile a body of work that represents what I love, and fear, about Milwaukee. I love my city’s lack of pretension; its stubbornness and pride in the unpolished corners. I fear that my city faces an uncertain future-—that as it becomes more divided it may push our best and brightest to find somewhere else to shine.

***

Excerpted from the introduction to Milwaukee Noir, “Disturbing Reverberations,” by Tim Hennessy, copyright 2019 by Tim Hennessy, included in the anthology Milwaukee Noir edited by Tim Hennessy. Used with permission of the author and Akashic Books (akashicbooks.com).