Pain is a fascinating, contrary experience. Our bodies have evolved this neurological warning system, making us feel terrible in order to better survive. Burn your hand? Get away from the fire. Leg killing you? Stop walking on it before you break another bone, idiot. We don’t live to hurt, but we hurt to live.

Physical pain isn’t a thought or emotion. It’s a complex response network whose job is to hijack our bodies, order us to pay attention, to react, and the way it works is wild. Receptors are stationed around our body like little watchtowers, tons on our skin and in our extremities—the places we’re more likely to get into trouble—and less of them internally where other systems can be trusted to take care of business. When one of the watchtowers senses danger it sends a message to our brain along one of two nerve paths—the first path is the high alert, “YOU’RE ON FIRE! YOU’RE ACTIVELY BURNING RIGHT NOW” alarm. It causes sudden, sharp pain and an immediate response. The second path is more lowkey; it takes the scenic route and transmits messages slowly, causing the dull, throbbing pain that reminds us of a continuing injury, a part of the body we shouldn’t be relying on yet.

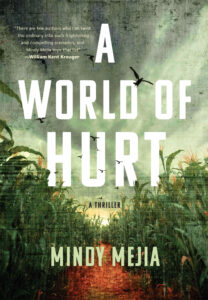

Writers have another name for pain—conflict—and when crafting narratives, conflict is our bread and butter. There is no story without conflict, no character growth without pain. When I began writing A World of Hurt, the second book in my Iowa Mysteries series about a police officer and a reformed drug trafficker who reluctantly team up to take down the remains of a drug empire, pain took a surprisingly central role.

Max Summerlin and Kara Johnson, the two main characters in A World of Hurt, are opposites in many ways. He’s a cop and she’s a criminal. Max puts duty ahead of his loved ones, while Kara would set the world on fire for the sake of one person. Unsurprisingly, their experience with pain is also starkly different.

Max has been shot twice in the line of duty and deals with chronic nerve pain that constantly impinges on his daily life, fueling his insomnia, his insecurity at work, and his troubled family life. His encounters with addiction as a police officer make him refuse any prescription painkillers, leaving him to suffer with no guaranteed recovery in sight. Max’s health is unfortunately not uncommon. Neuropathic pain affects more than sixteen million Americans who navigate a broken healthcare system, vague treatment plans, and uncertain outcomes that can lead to anxiety, depression, and a host of other mental and physical health issues.

Kara’s health, by contrast, is anything but common. She wakes up mid-surgery in the opening scene of the book, more concerned over whether the police have tracked her down than the bullet being pulled out of her shoulder. Hours later, as she tries to leave town, she’s attacked by a trucker and beats him bloody without feeling a thing. Kara only recognizes pain by what it looks like on someone else. She’s one of the few people in the world with CIP Disorder, a congenital insensitivity to pain. A mutation in one of her genes yields malformed versions of a certain protein. The protein’s job description is solely to facilitate the transmission of pain messages but the malformed protein won’t allow them, preventing Kara’s brain from receiving the watchtowers’ pain signals. I’m no doctor, but basically the defective protein is Gandalf and the pain messages are Balrog the fire demon and they shall not pass. Which sounds great, right? To be impervious to pain seems like a real-life superpower. The truth is we should be rooting for the fire demon. Without pain telling them what they can and can’t do, most people with CIP Disorder don’t survive past their twenties. Kara, who is approaching her twenty-seventh birthday and living anything but a cautious life, is painfully aware of this.

The medical community has long been fascinated with CIP Disorder and rightfully so. Medical health professionals have the unenviable task of quantifying our pain. They employ pain scales, asking patients to rank their suffering from one to ten. One being “ouch” and ten being “kill me now, please”, even though words, cognition, and your entire identity fade away before you even hit nine. They’re in the business of physical pain management and their tools are sadly limited. Medication, physical and mental therapy, and acupuncture are the main prescriptions to alleviate pain and the opioid crisis has complicated those offerings. For people who live on the 5-10 side of the pain scale, opioid addiction can make a terrible situation that much worse. Researchers are searching for compounds that duplicate the effects of CIP disorder, the ability to turn off overactive pain highways without affecting other bodily functions or causing life-altering side effects.

Understanding CIP disorder may lead to breakthroughs in treating physical pain, but mental and emotional pain don’t have a scale. They come with labyrinths instead of numbers, and while Kara may be immune to physical suffering, she grieves the death of her girlfriend, a woman who sacrificed herself to save Kara’s life. There is no neural pathway to block, no chemical capable of anesthetizing the pain of loss. Max may suffer daily, but he’s married to the love of his life. Who’s better off? Given the choice, which pain would you choose?

As Lord Byron, an objectively terrible human and his own brand of pain expert, said, “The great art of life is sensation, to feel that we exist, even in pain.” Max and Kara, for all their differences, have one fundamental thing in common: they know their lives through pain. The great art for them, in a world full of hurt, is to find a way to navigate it together.

***