Gauri Lankesh, an Indian journalist who frequently defended the rights of Muslims and other minority groups, was shot to death outside her home on Sept. 5, 2017. The crime, authorities say, was committed by men who objected to her acerbic comments about their brand of hardline Hinduism. Such extremists, many of whom are proudly anti-Muslim, have been increasingly emboldened under Narendra Modi, the country’s far-right Hindu prime minister since 2014. But the attempt to silence a dissenting voice had the opposite effect, inspiring large protests and drawing more attention to threats facing Indian journalists and democracy itself in a country of 1.4 billion people.

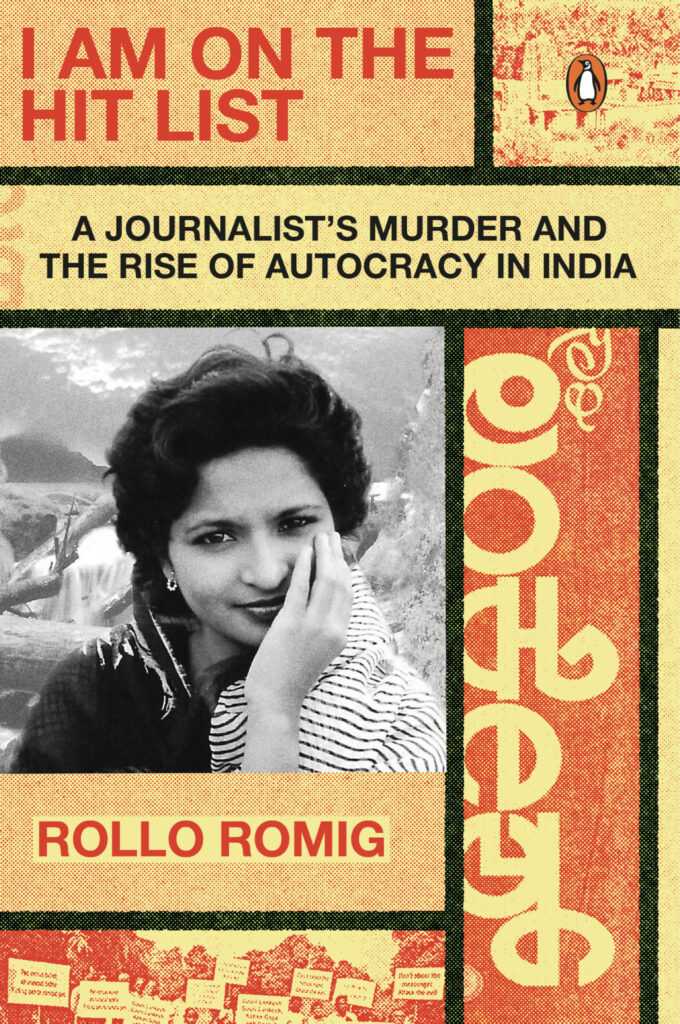

Rollo Romig, an American journalist, has been reporting from India for more than a decade. His new book, I Am on the Hit List: A Journalist’s Murder and the Rise of Autocracy in India, is an astute analysis of the case, which appears to be linked to the murders of other outspoken Indian writers. In a recent interview, he discussed the political climate in which the murder was committed, the suspiciously slow pace of the court case against the accused and the bravery of Indian reporters who continue to cover repressive government officials and their street-level enforcers.

Tell me a little about Gauri Lankesh. What kind of reporter was she?

She was a journalist in Bangalore, the capital of the state of Karnataka. Her father was an enormously important literary and journalistic figure in Karnataka. When he died, she took over the newspaper that he ran. She really described herself as an activist-journalist, and she was especially tuned into what was going on with the right-wing in India. She was extremely alarmed about the rise of autocracy under Narendra Modi.

And she didn’t hesitate to share these thoughts in print.

Her newspaper was serious in intent, but it didn’t shy away from the sensationalism and overt opinion-making that we associate with tabloids. Her paper’s circulation wasn’t big, but she had this outsized presence in the community of journalists and, especially, activists, though she didn’t seem like someone who would’ve been a prime target of assassination.

Meaning that she wasn’t really a prominent national critic of the Modi government?

She was known locally, but for a lot of Indians, her assassination was the first time they had heard of her. Nonetheless, the response to her assassination became a big national movement. There was shock that this middle-aged woman would be shot, alone on her doorstep, just coming home from work. There was an enormous protest movement in response to her murder.

And was it this sense of shock that drew you to the story?

Absolutely, that she was murdered in such a brutal way in a city that’s not known for its for gun violence at all. But beyond that, it was also the outpouring of the response, because she wasn’t the first person who had been assassinated. There was actually a string of assassinations of writers for several years.

The outpouring was so intense, it was clear that she had fostered this incredible network of activists and other people who loved her. That was my fascination with her: Who is this person who managed to connect and galvanize such a broad spectrum of people in South India?

Tell me about the string of murders of other writers.

There was a series of four murders that seemed suspiciously alike. All four were writers, all four were shot by gunmen who appeared out of the blue on a motorcycle.

Over how long a period?

The first murder was in 2013. Then there were two in 2015, and then there was Gauri Lankesh in 2017. So there were some gaps, but the pattern was very clear—it was even with the same kind of gun in each case. All four were activists just as much as they were writers.

The investigations into the earlier murders seem to have been completely incompetent. The cases seemed to go nowhere, so there was a lot of fear. As it became clear that there was a pattern, people wondered: Will this just keep continuing? Gauri talked about this: Who’s next?

Finally, the police who investigated Gauri’s murder made a breakthrough. The same group was allegedly behind all four murders.

Why were these men killing these writers?

The men who allegedly killed these four people were part of a group that was closely affiliated with a fringe right-wing religious group called Sanatan Sanstha, which has been described as a cult.

These are hardline Hindus.

They’re hardline Hindus. They’re associated with this movement called Hindutva, which can roughly be described as political Hinduism. And it is the same movement that Narendra Modi is associated with. The RSS and BJP (a Hindu nationalist organization and an associated political party led by Modi, respectively) are very much Hindutva groups. Their agenda, number one, is making India explicitly a Hindu country, and consigning everyone who’s not a Hindu to second-class citizenship, essentially. Especially Muslims.

India’s Muslim population is around 15 percent of the overall population, a distinct minority. But it’s important to say that it’s one of the largest Muslim populations in the world—about the same size as the entire Muslim population of Pakistan. So even though it’s a small minority, that’s within the context of enormous India. The fact that this huge population of Muslims is increasingly oppressed is a really big problem in India. This was an issue that Gauri was especially concerned about. It became one of her signature causes as a journalist and an activist—combating the vilification and oppression of Muslims.

Is this something she had in common with some or all of the other writers who were killed?

It wasn’t necessarily the other writers’ signature cause. The first writer who was murdered, his signature cause was anti-superstition—fighting against practices that are exploitative, that are used by con men posing as religious gurus, that are abusive towards religious minorities or against so-called lower caste people.

Each had their own signature cause. That was the thing that made it difficult to figure out what the pattern was, because they weren’t all unified in their main priorities, even though they were all progressive writers, to be sure.

These cases, as you write, have taken years to move through the Indian courts. Does this have anything to do with the fact that the people running the country are at least somewhat sympathetic to these extremely hardline views?

It’s hard to see it otherwise. It’s difficult to directly prove these things, partly because the Indian justice system is notoriously sluggish. It’s not unusual for court cases to take decades.

But putting aside the expected sluggishness, it still looks like the powers that be have no real interest in rushing this.

If they want to expedite a case, they can and they have not. It’s been pretty clear that the BJP has deliberately tried to stall Gauri’s trial in particular. The first arrests of the group of men who’ve been accused of murdering her happened six years ago. The trial began in 2021, and there is no sign that it will end anytime soon. They only hold sessions in the trial five days a month. And then many of those days end up being holidays, or the judge gets a cold or something. So it ends up only being a couple of days.

As a journalist writing about the murder of a journalist, have you feared for your own safety? Or going forward after the publication of this book, is that on your mind?

It certainly has crossed my mind. But honestly, it’s very clear to me that I have the protections of privilege—the protection of coming into India on an American passport, the protection of being a white guy. I’ve got a lot of unearned advantages when it comes to safety. I see writing a book like this as an opportunity to leverage some of those privileges to get the word out about what a lot of these really brave Indian journalists have been saying—and continue to say—under great personal threat.

This book is built on the work of countless Indian journalists. I just marvel at the bravery of these journalists under these incredibly threatening circumstances, where jail is a real possibility, where murder is a real possibility.