What is a “monster”? What is monstrosity? The definition depends upon who is doing the defining.

The etymology of the word “monster” is complicated.

“Monēre” is the root of “monstrum” and means to warn and instruct. Saint Augustine proposed the following interpretation, considering monsters part of the natural design of the world, deliberately created by God for His own reasons: spreading “abroad a multitude of those marvels which are called monsters, portents, prodigies, phenomena . . . They say that they are called ‘monsters,’ because they demonstrate or signify something; ‘portents’ because they portend something; and so forth . . . ought to demonstrate, portend, predict that God will bring to pass what He has foretold regarding the bodies of men, no difficulty preventing Him, no law of nature prescribing to Him His limit.”

In Old English, the monster Grendel was an “aglæca,” a word related to “aglæc”: “calamity, terror, distress, oppression.” A few centuries later, the Middle English word “monstre”—used as a noun and derived from Anglo-French, and the Latin “monstrum”—came into use, referring to an aberrant occurrence, usually biological, that was taken as a sign that something was wrong within the natural order. So abnormal animals or humans were regarded as signs or omens of impending evil. Then, in the 1550s, the definition began to include a “person of inhuman cruelty or wickedness, person regarded with horror because of moral deformity.” At the same time, the term began to be used as an adjective to describe something of vast size.

The usage has evolved over time and the concept has become less subtle and more extreme, so that today most people consider a monster something inhuman, ugly and repulsive and intent on the destruction of everything around it. Or a human who commits atrocities. The word also usually connotes something wrong or evil; a monster is generally morally objectionable, in addition to being physically or psychologically hideous, and/or a freak of nature, and sometimes the term is applied figuratively to a person with an overwhelming appetite (sexual in addition to culinary) or a person who does horrible things.

Since humans began telling stories, monsters have figured in them. There’s a rich tradition of monsters in literature. In Greek myth there are many monsters, a good number of them created by the gods as punishment for perceived slights. For example, Medusa was raped by Poseidon in the goddess Athena’s temple. Athena then punished her for desecrating her sacred space by cursing Medusa with a head full of snakes and a gaze that turns men to stone. The Minotaur was born of human and bull from a situation fostered by Poseidon to punish King Minos for backing out of a sacrifice. Minos’ wife Pasiphaë was cursed to feel lust for a bull and mated with it. From that union came the Minotaur. Lamia was the daughter of Poseidon, and her exquisite beauty drew the attention of Zeus. Lamia eventually became Zeus’ mistress, much to the displeasure of his wife, Hera. The jealous wife cursed Lamia, and the curse is what led to the queen becoming known as a child-eating demon. Etc. etc. etc. So should we be surprised that we might feel sympathy for some monsters when they so often seem created solely to punish women for male transgressions against them?

Less morally objectionable with regard to their origins are Arabian fire demons known as Afrits and Ghuls (which became Ghouls, when Westernized); Japanese Fox-maidens; the Mesopotamian Ekimmu, which are said to suck life force, energy, or sometimes, misery; the Inkanyamba, a huge carnivorous eel-like animal in the legends of the Zulu and Xhosa people of South Africa; and huge Ogres that are a staple in African folktales. Bad fairies, evil witches, crafty wolves, and nasty trolls that terrorize and/or eat humans in fairy and folktales from Europe fit in perfectly with this crowd of international monsters.

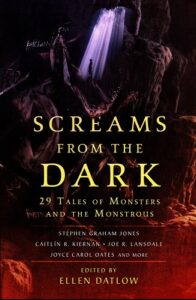

There are many different kinds of monsters represented within these pages—including vampires, werewolves, shape-shifters, changelings, human monsters who are unaware of the pain they cause, and the other kind all too well aware, yet indifferent to it.

Sometimes the monstrous requires a shift in perspective. Who is the worse monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein? The creature abandoned to his own devices by his creator or the prideful Victor Frankenstein? What if you have an ethical choice to make in order to survive? If a child is murderous and isn’t aware of what she is doing, is she monstrous? Outside circumstances or pressure can create monstrous behavior. Does that behavior make the perpetrator a monster?

Even our most insightful critics are divided in their appraisals of monsters and the monstrous. Noël Carroll, in his study The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart, writes of an “entity-based” scheme of horror, in which beings that defy neat cultural categories of what is “known”—in other words, the monstrous—arouse a sense of threat, or feelings of disgust. Conversely, as David J. Skal writes in his chapter on monsters in the popular culture of the 1960s in The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, “Monsters . . .

provided an element of reassurance. They were transcendent resurrection figures, beings who couldn’t die.” The monsters of television and film were appreciated as cultural touchstones because we all shared in our experience of them together: at the movie theater or drive-in; on television; and in magazines like Famous Monsters of Filmland, whose readers, mostly teenagers, may even have identified with them.

Stephen King, in his now-classic study Danse Macabre, may have put his finger on how we define the monstrous, and the hold of monsters on our psyche, but not with regard to the usual channels horror provides us. He considers the sideshow attractions of Tod Browning’s film Freaks; the polymorphous villains of Dick Tracy cartoons; and even the supposed “abnormality” of the overweight, or the left-handed. Why do such examples pique our interest, he asks, indirectly, before answering, directly: “We love and need the concept of monstrosity because it is a reaffirmation of the order we all crave as human beings and let me further suggest that it is not the physical or mental aberration in itself which horrifies us, but rather the lack of order which these aberrations seem to imply.”

What’s most interesting to me as a reader is the range of monstrousness that exists within ourselves and that we impose on the creatures unlike us that we name monsters. Monsters are our mirrors: in them, we see who we hope we are not, in order to understand who we are.

_______________________________________